It’s an unwritten law in the history of cinema that experimental—avant-garde, non-narrative—movies are fine as long they’re under twenty-five minutes or so. That’s about as long, it is thought, that even a seasoned cinephile can tolerate movieness without the progressive, empathic guiding hand of story. And it’s hardly an urban legend—ninety-nine percent of audiences demand narrative with their visual seductions, to the extent that for most people what’s vital about a movie is “what it’s about,” a state of affairs that has stood since 1903. For these masses the very idea of watching an 80 or 100 minute film that does not have a plot of some type is not only terrifying but flabbergasting—if it doesn’t tell a story, What does it do?

The question is the problem—for an experimental filmmaker, films don’t do, they are. To turn that train around, you have to try to reinvent the presumptions of the medium (which are, let’s face it, corporate capitalist at heart) and thereby liberate the form. Needless to say, watching a non-narrative feature isn’t passive—you put your game face on, send up your best antennae and consider moment to moment what movies are. Because they aren’t only what you thought they were. (Skip to Part II of this list.)

1. Sophie’s Place (Lawrence Jordan, 1986)

Despite inventing a style that Terry Gilliam made into a ubiquitous joke with the Flying Circus, Jordan’s animated antiquaries may be the perfect “New American Cinema” gateway drug—they are gorgeous, epiphanic, figurative and ceaselessly surreal, and they never stop moving. This World’s-Fair-in-a-fever-dream masterpiece is as charming as it is inexplicable; Jordan’s sudden transformations (Victorian dandies are butterflies are hot-air balloons are locomotives are rosebuds are skulls) make no sense except for the only sense only movies can make: ecstatic, visceral, poetic sense. It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that Jordan’s film are particularly bewitching to children—the mixing of hundreds of 19th-century engravings creates a breathless cataract of fantastic moviescapes where reason and scale evaporate and whim reigns.

2. 23rd Psalm Branch (Stan Brakhage, 1967)

Brakhage’s films are timeless—they could be the first films ever made, or they could come from an unfathomble future; either way, they are simultaneously the diametrical opposite of what we think of as “movies” and a precise expression of cinema’s elemental factors. (Which may be another way of saying what we ordinarily think of as cinema has more in common with theater, novels, circus and video games than movie-ness. Or at least Brakhage would think so.) “Poetic” Brakhage has been labeled by his acolytes, but it’s not the lyrical connectiveness of verse that’s intended—it’s the purely optical suggestiveness of images, abstracted away from their received meanings (as text, not as real objects), and from the reflexive significances we attach to experiences of film and photography. This anti-war howl is not “about” war but only itself, about the newsreel footage it collects and despoils in an editing-room assault that shrieks, silently, with anxiety, from Holocaust footage to perusals of fresh dead meat. The film never leaves you with one image for long and even resists the musical tendency to hit us with emotionally satisfying rhythms—it’s an asyncopated epic. With Brakhage there’s no escape, and any room in which 23rd Psalm Branch plays becomes a funeral chamber.

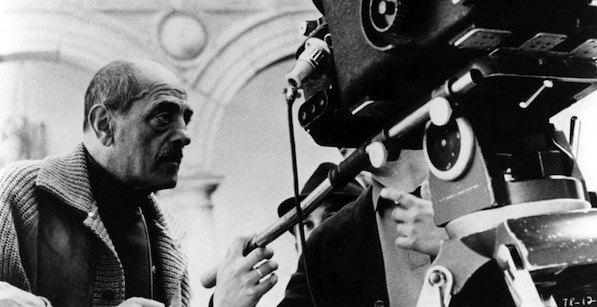

3. L’Age d’Or (Luis Buñuel, 1930)

The first avant-garde feature, and the first movie made with express purpose of destroying the society that sees it. I’ve made a swooning anarchist’s case for this here and there’s just no outdoing it.

4. Blue (Derek Jarman, 1993)

Derek Jarman, dead in 1994 from AIDS, at the age of 52, was the new queer cinema’s jester prince; he never made a film that doesn’t manifest on the screen as an unpredictably impish riff on serious matters, Art-making, and Sex and Death. Always risk-mad, he made other strictly narrative-free films, including the incendiary The Last of England (1987), but this nosethumbing landmark, Jarman’s terminal work, dares the most. Famously, it’s hardly a movie, but a complex narration and soundtrack playing behind (beside? atop?) an empty but bright blue screen. (It takes Godard and Gorin’s Letter to Jane one step further, from one image to none; it’s closest corollary might be a radio play.) Jarman’s text, about the decay of his body and eyesight in the grip of AIDS, and about his closing life already emptied of friends and lovers, is wry and intimate, and its relationship with what you’re seeing—and not seeing—is, to say the least, disquieting. Blue is intended to be seen in a darkened theater, where the relentless color amounts to an optical attack, and ends up playing tricks on your eyes. On home screens, the experience is closer to seeing a Caravaggio in a text book: edifying and necessary, but no replacement for being there.

5. Alice (Jan Svankmajer, 1988)

Famously a die-hard Surrealist who still “belongs” to recalcitrant Surrealist federation in the Czech Republic, Svankmajer has been exploring the anxiety of everyday things for over 40 years, and in a vast variety of forms (including poetry, sculpture, painting, ceramics, collages, and cabineted creations fashioned largely from taxidermied animals). Of course he is predominantly a stop-motion animator, inheriting the Czech puppet tradition and forcing it down the gullet of his own noxious id. His filmography is basically one long smash-up of subconscious fears, cultural recyclings, sociosexual commentary, food used in ways it shouldn’t be, things that shouldn’t be food but are, dream frustration, and a crystalline faith in the desire of objects. His version of “Alice in Wonderland” might have a smattering of connective narrative thread, but is mostly passionate about mustering an uncomfortable physical world of unpleasant juxtapositions, mucous mixtures, semi-animated impossibilities, revolting taxidermic tension, and a pervasive sense of real childhood danger (without, fascinatingly enough, inciting the merest drop of anxiety from his star, placid blond tyke Kristyna Kohoutova). Self-referential and playfully conscious of pedophiliac threat as only a Surrealist’s film could be, Alice does Carroll better than Carroll did Carroll, swapping the smarmy wordplay and faux innocence for the claustrophobia and stress you taste in a real dream.

6. Decasia (Bill Morrison, 2002)

Simply, an almost random assemblage of ancient silent film footage beset by nitrate decay. Usually we’re compelled to watch silent footage because of how beautifully it’s been restored or preserved; in Morrison’s influential film, the fragile and mortal nature of film stock is the raison d’etre, and as such Decasia can on one prosaic hand be taken as an advocacy statement for film preservation archives. But on the other, the film is as entranced by organic visual chaos as Brakhage’s, while the liquidy explosions of chemical rot are fantastically upsetting, giving you the impression that these captured yesteryear moments, these lives and people and places, are dissolving before your eyes, and once the entropy is complete, they’ll be gone forever. Thus, Decasia lays waste to a major part of cinema’s allure—the part that enables us to capture time, and revisit the past.

7. Diva Dolorosa (Peter Delpeut, 1999)

Another film simply assembled from old fragments: Delpeut’s Dutch film is an unnarrated ode constructed out of footage from a particular genre of Italian silent: the Black Romantic melodramas of the 1910s, in which tragically willful, independent fin-de-siecle aristocratic women self-destructed, dramatically and hyper-tragically, in the name of love. The genre, which pervaded other mediums as well, might be the first and last word on the communion between sex and death, and the clips Delpeut uses are chockablock with swoony melancholy and suicidal ardor. Many of them, despite their age, look remarkably accomplished as pieces of cinema; perhaps someday we will see complete editions of Rapsodia Satanica (1915) and La Donna Nuda (1914) (both, and others, starring the Black Romantic Garbo, Lyda Borelli). But Delpeut is crafting a found-object poem here, with a rhapsodic orchestral score and a sure sense of how so much weepy, proto-campy mega-sadness can collect in your head as a statement about its own culture, and also as a palpably beautiful, tragic spectacle despite the odor of antique cheese. Like Decasia, the movie is really about cinema itself, and therefore about lost time, and therein lies its loveliest sorrow.