[Editor’s note: While the new restoration of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari plays at Film Forum it is unavailable to Fandor viewers in the New York metropolitan area.]

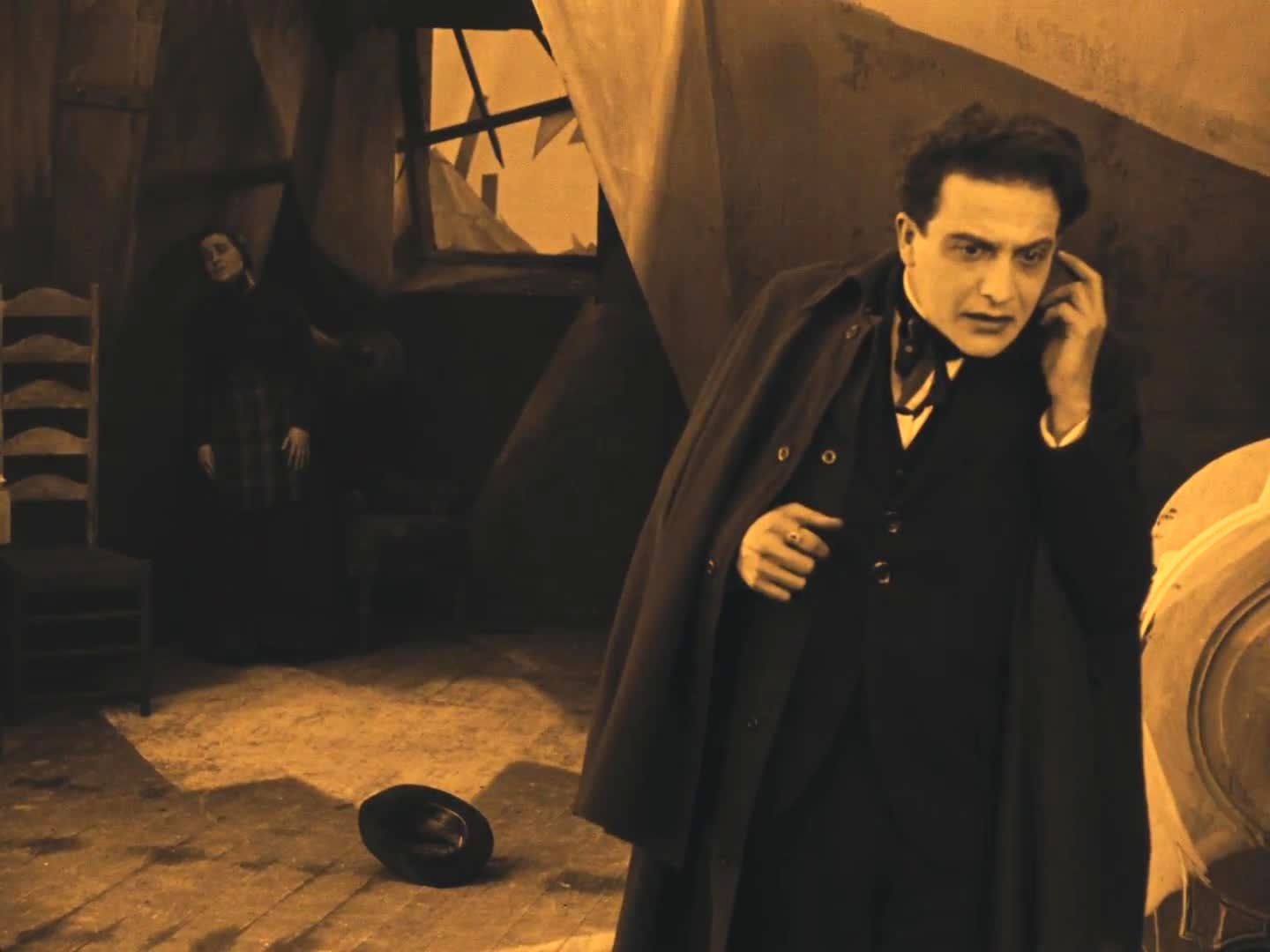

Writing years later, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari screenwriter Hans Janowitz recalled the moment during the film’s premiere at Berlin’s Marmorhaus on February 27, 1920, when Conrad Veidt, wan, still, upright in a coffin, opens his kohl-rimmed eyes for the first time and a woman in the audience let out a scream. Ghouls, devils, witches, gremlins, ghosts, vampires, zombies, Freddies and other beings that go thump in our night: we queue up to see them, hand over hard-earned pay, and wait to be scared as close to death as possible. The moviegoer lured by the poster of a bloody ax, the silhouette of an insatiable beast, or wide-eyed prey sends out the fervent plea: Make us believe. Fool me. Frighten me. Take me down the long dark corridor until something scary jumps out of the shadows. Reel me in until I scream.

Publicity campaigns build dread and excitement—“It’s not in your head. It’s in your house.” “Who Will Survive and What Will Be Left of Them? “The Monster Is Loose!” “Pray for Rosemary’s Baby” “Love Never Dies.” It is an ancient pitch that may go as far back as the gods painted on the walls of Ajanta—reverence induced by art. (What is fear but an extreme state of awe?) Cinema’s closest antecedent: the Fantasmagoria popularized by a French scientist/showman called “Robertson,” whose ghoulish late-18th century magic lantern spectacles relocated from the sixty-person capacity Pavillon de l’Échiquier to the expanse of the courtyard of the Convent of Capucines, which had been only recently emptied of its holy sisters by the French Revolution.

A February 1800 issue of Courrier of Spectacles—quoted in Laurent Mannoni’s The Great Art of Light and Shadow—describes the Fantasmagoria scene: “Storms, the harmonica, the funeral bell which calls the shades from their tombs, everything inspires a religious silence: the phantoms appear in the distance, they grow larger and come closer before your eyes and disappear with the speed of light. Robespierre comes out of his tomb, begins to stand, a thunderbolt falls and reduces the monster and his tomb to dust. Beloved shades appear to lighten the picture: Voltaire, Lavoisier, J.J. Rousseau appear in turn, and Diogenes, his lantern in his hand, searches for a man and and to find him goes up and down the rows, rudely causing fright to the ladies, which entertains everyone.”

Caligari’s promise to similarly frighten and entertain called out from posters on Berlin’s streets: “You Must Become Caligari,” a line taken from the film at the moment the doctor of the title is driven to take up evil deeds. Often thought of (incorrectly) as cinema’s primordial boo, Caligari promised much more than a passing scare. Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer wrote Caligari in Berlin, at that time a chaotic caldron of poverty, decadence, and bloody revolution, where the millions of dead and mangled casualties from World War I haunted every German family. Reportedly inspired by the sensationalist murder of a young woman in Hamburg and the popular detective serials of the time, their script also reflected their war-forged ideas about psychiatry and the mind. The result was an enduring horror beyond that of a creature suddenly appearing and eliciting a scream. There are scarier things, things you might not immediately know to fear. Things you initially have the inclination to trust.

Caligari was converted to the screen by what became a Who’s Who of German cinema. Erich Pommer shepherded the productions of F. W. Murnau’s Phantom, Faust, and The Last Laugh and Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse and Metropolis, among others, before pioneering the German musical in the early sound era. Director Robert Wiene had come from the theater as well as had written fourteen scripts for one of Germany’s biggest film stars, Henny Porten, and went on to build an impressive body of work before his death in 1938. Set designers Walter Röhrig and Hermann Warm became collaborators of Weimar cinema’s greatest names: Röhrig working with Murnau, and Warm, among other films, on Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr as art director. Scenarist Carl Mayer, about whose work cinematographer Karl Freund once noted, “A script by Carl Mayer is already a film,” wrote Wiene’s follow-up to Caligari, Genuine, and also collaborated on Murnau’s most famous films, later joining the director in the States.

These Blair Witch conjurers of their day drew from current distorted aesthetics, Cubism and Futurism, as well as small-town carnival kitsch and Freudian theories of the unconscious mind, to tell a multilayered tale of men driven to do bad things against their will. Caligari’s effect was immediate and far-reaching. “It set the tone for a decade of critical and commercial success,” writes scholar Ian Roberts. The film made it to New York in 1921, after Ernst Lubitsch’s wildly successfully Madame Dubarry broke through the war’s lingering embargo on Germany cinema. One reviewer, aware that the strange, arty film probably wouldn’t make it outside city limits, advised her readers: “Although you may never see [it], you ought to know about it because you will feel its influence in other pictures that are to come.”

Officially a sensation, it showed how a film’s mise-en-scène—everything from lighting to sets to costumes to the way actors walk—can be used to convey mindset, to project mood. It melded psyche and plot and cleared the way for the shadowy worlds of Murnau’s Nosferatu, the first in a hundred-year run of vampire features, and Arthur Robison’s Warning Shadows, a morality shadow play whose plot device borrows heavily from Caligari. In 1924’s The Hands of Orlac, about a pianist with transplanted hands, director Wiene, working again with Conrad Veidt, uses a very distant camera to shoot his main character, helpless and alone slowly going mad, in the corners of large overwhelming rooms.

While Expressionist cinema is confined to a small pool of German films in the mid-1920s, its influence spread far and wide. Outside Germany, Expressionism seeped into the Soviet Factory of the Eccentric Actor (FEKS), which unleashed a more playful chaos on cinema with its own form of stylized acting and distorted sets (see the impossibly high clerks’ stools in The Overcoat and its carnivalesque segments) and the French impressionists and their subjective camera, used to spooky, psychological effect by Jean Epstein in his adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher.

It trickled out through Hollywood to the atmospheric films of Borzage and von Sternberg, to film noir, monster movies, and the serial murder franchises down at the multiplex. Director James Whale reportedly screened a print of Caligari over and over before shooting Frankenstein. (Note the jagged horizon where evil deeds are carried out in silhouette and the female prey forever enshrouded in white.) Its influence reaches down as recently as Guy Maddin’s 1992 off-kilter Alpine village in Careful and 2010’s Shutter Island, which pays overt homage to Caligari with the round dark-rimmed spectacles worn by Max von Sydow’s sinister lobotomist, jagged shadows in the lighthouse walls, and a psyche ravaged by war. Whether you look for it in the art film or in the wide release, you can still find Caligari.

Imitating Caligari seems impossible—its singular fusion of modernist art and psychological terror, nevermind the story’s twist ending, render it a one-off, unique—but the temptation of repeat success is hard to pass up. Robert Wiene wrote in 1936 to friend Oskar Fischinger of an impending remake about to shoot in Paris, and producer Pommer and the screenwriters Janowitz and Mayer entered into a copyright dispute over who had the rights for a sound do-over. The 20th Century Fox studio took great liberties with the storyline and art design for its 1962 remake, and, in 2005, David Lee Fisher made what can only be described as a replica, with new actors, added dialogue, and sets recreated from the original. (Fisher’s is black and white, while the original appears in color: amber, blue, green, violet and brown.)

With all the talk about how Caligari changed filmmaking, it’s easy to forget that it also changed movie audiences. Describing a screening in the Carpathian mountains during the war, director Robert Wiene wrote that villagers, who were seeing film for the first time, “rushed screaming with fear from the dark room: you believed to have seen ghosts.” Once you knew they weren’t actual ghosts, the jig was up. Now wise to Caligari’s devices, the ante is continually upped by an increasingly literate public. More subtlety is required than a jagged window dooming the next victim in the plot.

Director David Fincher recently complained at a special screening of his latest film, Gone Girl, in New York, about audiences giving too much significance to the appearance of the board game Mastermind. “I think it was the only game we could legally clear…,” Indiewire quoted him as saying. “Part of the curse of working in cinema is that nothing is treated as accidental or off-handed. When you cut to something, it gets this weird importance, so you have to be careful.”

But such literacy doesn’t make today’s audiences completely immune to Caligari. One scene is particularly terrifying, even as you can see it coming. A figure all in black makes its way through the tromp d’oeil town. Clinging to the walls he creeps along to the desired window. Inside, a woman sleeps deeply, virginal white bedsheets and bedclothes mingled as one. The figure’s face, now clear, is framed in the distant window. He enters, drawing ever closer to the bed. He raises his dagger. Then suddenly stops. Bending over her, curious. She starts awake. He has no choice now. He grabs her. She struggles wildly, her face contorted in fear and desperation. He jerks her around violently. He drags her from the bed. The woman is now his limp puppet. She is carried out the window onto the roof.

How can it still be so frightening after all this time? Blame your weak brain. “It is certain that the illusion is complete,” writes a layman about a 1799 Fantasmagoria show. “The total darkness of the place, the choice of images, the astonishing magic of their truly terrifying growth, the conjuring which accompanies them, everything combines to strike your imagination, and to seize exclusively all your observational sense. Reason has told you well that these are mere phantoms, catoptric tricks devised with artistry, carried out with skill, presented with intelligence, your weakened brain can only believe what it is made to see, and we believe ourselves to be transported into another world and into other centuries.”