New York filmmaker Robert Greene moved from Brooklyn to Beacon, New York after making his sophomore feature, 2010’s Kati with an I. Prior to the move he’d made a home in NYC, working at Kim’s Video while attending City College (and after), and starting partnerships with distributors (4th Row Films) and cinematographers (Sean Price Williams). The big city was fruitful, but moving to a sleepy suburb was a family-focused necessity that brought with it a number of changes and a few fortuitous friends—among them actress Brandy Burre.

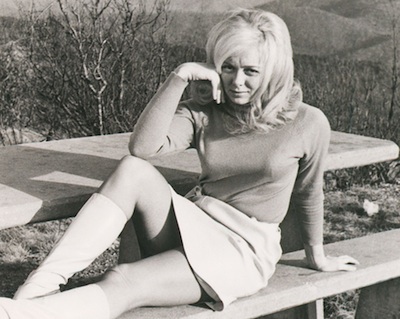

On a hiatus from her acting career, Burre had a presence Greene evidently felt, and the two started talking about making a documentary. Greene says, “I should say, I have many neighbors. I wouldn’t film all of them. Brandy’s fascinating.” Burre had acted professionally, most notably in a recurring role on HBO’s The Wire, but when she got pregnant she left acting and moved to Beacon, where her partner opened a restaurant and bought a house big enough for their family. This house would become the set and staging area for a host of performances, from domestic to theatrical, all starring Burre—a woman keenly aware of the effect of the camera and as attracted to it as she is threatened by it.

The result is Greene’s biggest production to date: Actress, a gem of a documentary, which asks if audiences can handle the truth- and fiction-smashing that happens when you put a camera in front of a person attuned to a life of perpetual broadcast. Less about this actress’ return to a career than about one woman’s inability to divorce acting and life, a big part of Actress asks where truth lies. “You’re aware of her [Burre’s] awareness, her truthfulness, authenticity, phoniness. You’re aware of all of it as you’re watching, and when it comes to the point you’re not sure what you’re watching, what you take from that says more about you than about Brandy.”

Actress would make a great double feature with Errol Morris’ Tabloid. Both are docs about women who are complicit in their own exploitation, and both ask you to judge women who are on self-inflicted trials for their transgressions. But where Tabloid wraps its dramas in the low-rent accoutrements of, well, tabloids, Actress is filled with reminders that the subject needs the viewer for her gains. She cries over dishes, breaks up her family, “rehearses” in her kitchen after she’s fallen apart over the state of the relationship she’s trashed—and it’s on the viewer to decide if she’s acting or acting out. Like I’m Still Here, this could be the newest, biggest audition tape ever; Burre does end the film with a return to the field.

Tensions about truth have always been inherent within the documentary genre. But instead of asking if Michael Moore is standing in front of real nukes (Bowling for Columbine) or if Nick Broomfield is making fun of legal prostitutes (Chicken Ranch), Actress presents Burre’s successes as rewards and her injuries as punishments, because we’re watching a movie. Our expectations about her actions hinge on our abilities to accept the film as the record of a life or the record of an actress. “Often times, we look at women and say, ‘She’s doing this thing’ instead of ‘I’m feeling this and projecting it onto this person’,” Greene says. “It’s my goal for the audience to question things. ‘Did Brandy break up her family to get back into acting?’ And many moments later you’ll ask, ‘Why did I think she’d break up her family to get back into acting?'”

Greene’s first documentary, 2009’s Owning the Weather, was inspired by a Harper’s piece on climate control. With the participation of the article’s author (Ando Arike), Greene produced a fairly conventional doc that left him a bit pigeonholed. “I learned a lot of lessons about how I didn’t want to make films by making that one. I would get frustrated when we were shooting it because I wanted to deal with tiny things, but the subject was the weather.”

His response to that lesson was to find a subject near to him and focus on just the “tiny things.” He chose his half-sister, Kati, a teen in love with a boy who’s thinking about leaving town just as she finds out she’s pregnant. “For Kati, we only paid attention to the smaller things, to see what we could find in them.”

The shoot took three days. Read that, and realize film editors famously evade documentary because production can take years—and that’s in cases when the film is actually completed. Greene evaded this problem entirely with Kati, and between his ideas and the work he was doing for 4th Row Films, he began fine-tuning a process of production that made the supposedly least- expensive genre just that. Kati trades the expanse and formality of Owning the Weather for something that’s introspective and intimate.

Greene’s production approach involved a kind of loose scripting. “I wanted scenes that spoke to what and who Kati was at the moment we filmed. We have the mall scene—every teen drives to the mall—and it’s what she’d do without direction, but even that I directed. I think it’s best when structure and ideas are operating against the chaos of reality. The intermingling creates something new.”

Sean Price Williams shot parts of the film with Greene, and the two were clearly of the same mind about the sovereignty of their subject. A pretty teen, Kati is easy to sexualize, and despite a narrative turn that reveals she is sexually active, this is one girl not getting played for her prurient appeal. Comparing Kati to Greene’s next film, a doc about amateur wrestlers in the South called Fake It So Real, you’ll naturally think Greene flew from the most delicately feminine subject to the most flagrantly masculine one.

Fake It So Real follows a handful of self-employed wrestlers the week before an annual competition; it makes Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler look like an expose on “show.” These wrestlers don spandex and face paint, wax prosaic about their working-class jobs and are lucky to break even on their investment in the upcoming match. Their dedication recalls scenes from other sports movies about why the athletes stay determined—I often thought of the moment in Whip It when an aging Juliette Lewis threatens teen recruit Ellen Page by saying that roller derby is “all I’ve got.” The same sentiment is true for Fake It So Real, and it can be felt through the bluster of male peacocking, but it’s never stated outright. Greene says, “You never know how much of Fake It is staged or worked out, but [when] you watch them in the ring, it’s a very real performance.”

Greene discovered these amateur wrestlers through his cousin, Chris Solar, and stresses that his attachment to the show is not ironic. It’s as if removing ironic distance is a way of admitting not just sincerity, but immersion in the experience of others; the experience of a subject and a reality unmitigated by critical principles or the rules of art. “There was a review in Indiewire that said Kati gave the best performance of the year, and it revealed something about my films I hadn’t mined: they’re about social and formed identifies. Kati’s a sponge, and young, and she regurgitated ideas that reality would come in and sweep away. In Fake It you’re seeing these men who think of themselves a certain way, and [their wrestling personas] are characters themselves. Then their documentary characters become other players. What was [an interesting concept] for Kati became real for Fake It So Real.”

4th Row Films’ Susan Bedusa produced Actress; after watching Greene make films about two family members, she cautioned Greene about making another film about someone close to him. Greene’s response was pragmatic: “I can get this done without investors or anything in the way.” And with the complicity of his neighbor-turned-subject Burre, he started shooting in her home on a loose schedule. “You’re aware when she’s playing, picking words, leading the camera. Her awareness helps you challenge how you see the film and filmmaking. Actress is a film about documentaries and how you perceive the relationship between the camera and the subject; performance is part of that.”

Greene realizes the script is flipped when the subject is a professional performer. Burre is always performing, and that calls to question her authenticity in any exchange. “When she’s expressing feelings and undergoing troubles there’s theatricality everywhere.” Which is to say, we spend at least part of the film judging Burre’s sincerity, wondering if she’s phony, asking ourselves if she’s a handful worth having, and Greene somewhat sympathizes. “We were interested in taking the things that aren’t usually spoken about in docs—manipulation, exploitation—and putting it on the surface. I want to make clear that social performance is a slippery thing. The layers of reality in the film match a sense of how life is layers of reality, and the idea of being a mom, a sexy woman, an actor, the subject of a documentary and a friend are all slippery and dip into each other. They move around, and they’re frisky and pliable. The goal was to take these things films [usually] obscure, and put them onscreen to increase the tension and develop a better understanding of what’s going on in her head and in her life.”

It occurs to me as Greene speaks that I’m reaching for other films to contextualize his ideas. When he says “she’s exploiting her own vulnerability,” my mind moves to The Act of Killing—a film which shares no common ground with Actress except a quasi art-therapy approach to producing catharsis in the film’s subject. It isn’t enough that we’ve witnessed something that implicates us so directly; when we watch Actress, we also see the filmmaker and the subject in collaboration.

Unlike the interrogatory intrusions of Sherman’s March director Ross McElwee, Greene’s voice is implicit and unheard, but it’s not fair to say he doesn’t ask questions. “Though the film our relationship became something different. We collaborated on a very tough movie to make that exposes both of us, especially her, and it became an art project—it was a tool for Brandy’s expression and I was holding on for the ride. We never could have predicted what happened on camera. I knew it was bubbling out of the surface but I didn’t expect the movie to become that.”