Austrian avant-garde filmmaker, exhibition-and-festival curator, lecturer, author and, yes, tsar of found footage Peter Tscherkassky stays faithful to manual processes and traditional montage methods in an era of overbearing digital ease. His autonomous creations are based on already existing audiovisual materials that he manipulates meticulously. (“If you look carefully enough,” he says, “there is a hidden film, at least one, in any piece of footage that you can find.”) What comes to life and at his editing desk, in the darkroom, with a little bit of red light, is work that remains an ongoing exploration of aesthetic limits. I got the chance to space with Tscherkassky this past year at New Horizons.

Keyframe: I feel like most of your films are…

Peter Tscherkassky: … very kinetic?

Keyframe: … and very consistent, coherent as an œuvre. To me the idea of movement seems to be one of those recurring motifs.

Tscherkassky: My main artistic focus is the materiality of film. I haven’t been thinking about the movement within film that much… but of course movement happens. For many people that is what cinema is about. But by deconstructing film I destroy the illusion of movement it normally creates.

Keyframe: Moving images.

Tscherkassky: Yes. One might say that film is not movement at all. Take any film strip in your hands and look at it: You will clearly see that there is nothing moving. What you see are still images. Separated still images, single photographs. And this is what I work with—still images, a frame-by-frame creation.

Keyframe: How do you find material for your films?

Tscherkassky: I pick up footage wherever I can get it, but I don’t really search for any particular footage. Once I get some I decide whether I want to make something out of it or not. But basically, if you look carefully enough, there is a hidden film, at least one, in any piece of footage that you can find.

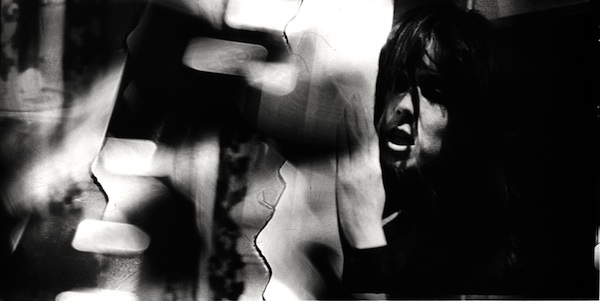

What I do next is to sit down in a darkroom, with a tiny little bit of red light. I work with orthochromatic material, that’s why I can use red light; I have to see what I’m doing, otherwise my work wouldn’t be possible. That’s my work situation: dimmed light, just a little bit of red light, and than I start to paint with light, with a laser pointer and little flashlights, onto the found footage, which lays on top of unexposed footage. Frame by frame, over and over again, copying tiny little bits of the original frames onto the orthochromatic footage. And I do that for 1,5, maybe even 2 years, than the film is finished. Once it’s finished I take it to the cinema and all of a sudden my film explodes on the screen into movement. It gives me goosebumps just to think of it…

Keyframe: I heard an anecdote or a rumor!—about your audience. After one of your screenings started, somebody alarmed the projection room that something is wrong with the copy, it’s scratched, broken. But it was fine. It was just one of your films. Does it happen very often?

Tscherkassky: Well, it happens sometimes. Especially with L’Arrivée (1997/98), a film in which you see the film strip entering the screen from the side. That’s the way I printed the found footage onto the raw footage. And what you hear is the sound created by the pictures of the found footage, which were printed over the sound strip–you actually can hear the picture. And since L’Arrivée has no classical sound strip sometimes projectionists get really confused, because it says “Dolby SR” on the can and instead of having a Dolby SR sound strip, they see pictures printed across the sound strip….

In earlier times it happened that people tried to actually stop the projection. This was the case with Parallel Space: Inter-View (1992). I know of a screening organized by the American filmmaker David Gatten who had to block the projection booth to prevent people from stopping the projection! And Film of love, Liebesfilm (1982), where you see the movement of a couple kissing each other repeated 722 times. It happened twice that people tried to stop it.

Keyframe: They thought it jammed?

Tscherkassky: No, they just hated the film. [Laughs]. It wasn’t about technical issues, they just couldn’t bare the physical experience. My films have three distributors and when they’re shown I usually don’t know what happens during the screening, and I don’t even want to know, because I’m absolutely sure that sometimes everything goes wrong.

Keyframe: Obviously your films are very challenging for the audience. Is such reaction important to you?

Tscherkassky: When I’m working I’m not thinking about my audience. I make films that I like to make and I like to watch, basically. Every art form has a core which cannot be translated into another medium, into another language. It’s a core that is unique to that medium. And for me one of the main characteristics of that core, when it comes to film, is that possibility to say or transmit several messages at the same time. For me that core are superimpositions, velocity, and the possibility of high speed communication. twenty-four single units per second, which can be extended into a really large space, if you use CinemaScope as I do. That’s what interests me about film art and I find it very exciting to be challenged like that by others. But to challenge the viewer is not my main goal.

Keyframe: If I was a random viewer, how would you explain to me what found footage is?

Tscherkassky: It’s the simplest way to avoid a situation in which you have to make a decision what to shoot. [Laughs]. Because it has already been done. And all of my films are a kind of meta-cinema, so it’s quite natural for me to use a finished film for a new start to create my meta-cinema, so to speak.

Keyframe: You once said it’s the material that creates the film. ‘Medium is the message?’ Somehow this observation clicks with my other observation: your films are not so emotional. Unlike, for example, the first film manipulating the physical material I ever saw, Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses.

Tscherkassky: It depends. If you take Happy-End (1996) or Parallel Space, that’s very emotional, I think. Not right away, but it builds up during the film… Also Dream Work (2001)… But I understand what you mean. Carolee Schneemann intended something completely different with her manipulations. What I do is to show the beauty of something which is vanishing, just at the very moment as it vanishes–that is analog cinema. And Schneemann’s work is clearly not about that…

Keyframe: I think she’s trying to evoke emotions that were already there and in your film emotions happen when watching.

Tscherkassky: That’s a good observation.

Keyframe: Your films are like a meeting of the viewer and the film, cinema in action, not so much bringing across any particular message.

Tscherkassky: It’s about the moment, the synchronicity. Not on a diachronic level, but it’s like poetry. It happens now and now and now and now.

Keyframe: What’s ‘now’ is digital. Are your considering becoming friends with modern technologies?

Tscherkassky: At one Q&A [during the T-mobile New Horizons International Film Festival in 2012] I was asked whether I’d like to try and work with 3D or other really advanced new technologies to create something completely new… I said that I’m not at all interested in digital esthetics by now, I’m still working with analog film and thinking within its specific possibilities, because it’s vanishing, that’s just a matter of a few years. Only a few places will be left to screen analog film and I’ll have to decide if I should go on with analog cinema, simply because it’s no fun to create artwork if so much work is involved as in my case, that finally can only be shown in fifteen cinematheques, worldwide.

Keyframe: Your work is very elaborate. Is there ever any room for anything coincidental?

Tscherkassky: There’s so much work involved that I have to be absolutely convinced about what I’m going to do as a next step. And in order to reach that point, I have to be really prepared. Of course unplanned things happen, too, there is an element of chance involved. But basically when I’m in the darkroom I know exactly what I’m doing. Most of the time I spend in my kitchen studio—that’s how I call it—I sit in the kitchen, maybe smoking a cigarette if I’m nervous, and thinking about the next step. And then going back to the editing table and selecting the material which I’m going to use in the darkroom. As you can tell from the films, my stories evolve step by step by step, in a way that it all makes sense, hopefully. There’s no element of chance involved story-wise. But if I sit in the darkroom and do my hand printing… If I print her face for example [points at a friend]… I print one frame and then move on to the next frame, and the film strip is very dark, so I can barely see her face on it… so I try to hit the frame with my laser pointer where I think her face could be… and sometimes I don’t get it immediately, so I have to start moving around within the frame with my light beam, looking for her face. ‘Where is she?’—’Oh, here she is!’…. and in the next frame I missed her completely: ‘Where’s her face?!?’… then I realize she turned her head—that is the chance aspect of my work, and this is what they call ‘the human touch.’ I could never do that with a computer. I could not tell it: ‘Copy her face, but don’t find it immediately, you have to look for it, before you find it.’ The computer would say: ‘What? Are you nuts?’. . .

Keyframe: An element of chance within a very precisely planned scheme.

Tscherkassky: Yes, exactly.

Keyframe: How does a fact that your partner Eve Heller is also a film artist help you in your creative process?

Tscherkassky: With my latest film, Coming Attractions (2010) Eve helped me a great deal with the editing. But so far we don’t create films together. Eve has a quite different approach to film. It neither helps nor disturbs me, that Eve is a film artist, too.

Keyframe: Do you see your art influencing other filmmakers? Is it important to you?

Tscherkassky: Every good artist has to find his own voice, otherwise she or he wouldn’t be a good artist. You have to find your unique style. One of the greatest compliments I ever got came from Virgil Widrich, an Austrian filmmaker who makes short and feature lengths films, and was nominated for an Oscar for his film Copy Shop. Way back in 1999 he was sitting in a cinema, and that was the year when I made the official trailer for the international Austrian film festival Viennale. He didn’t know that. The screening started, and before the main movie my Viennale trailer came on, and Virgil said: ‘After two frames I knew it was a Tscherkassky’… That’s what I mean by ‘own voice.’ But of course everybody is influenced by others, we are all parts of the same culture, it’s all connected. So the uniqueness of your voice is more less an illusion. Somehow it fits into our culture, otherwise the audience wouldn’t follow and your work would be completely misunderstood or not understood at all.

I could say that in my case it was the concept of the single still frame as the basic unit for film art, which comes from Peter Kubelka—that really influenced me. And the possibility of superimposition and communicating in a very dense way as exemplified by the films of Pat O’Neill. Kubelka and Pat O’Neill—these were my main influences.

But if I influenced anyone—I don’t know… Are you familiar with the films of Siegfried A. Fruhauf? A former student of mine, now a very good filmmaker. He works with darkroom techniques as well, but he has found his own voice, is really emancipated by now. It’s always about the main idea, and the results should look completely different, even though we have a common cultural background.