You’ve got to understand, there’s something about him. Something to do with death.

—Jason Robards in Once Upon a Time in The West (Sergio Leone, 1969)

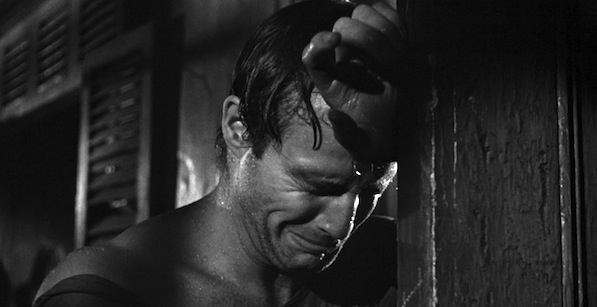

In Elia Kazan’s screen adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), Vivien Leigh as Blanche DuBois gets to call Marlon Brando some good names: “common,” “primitive,” “animal,” “subhuman” and possessed of a “brutal desire.” Underneath the alibi of the film’s realism—which looks extremely artificial today, like all bygone realisms—an extremely potent sexual fantasy takes charge: Brando as Kowalski, the glorious working class beast of a man, a libidinal feast for the eyes of female viewers and, just as explicitly, a fount of narcissistic delight for male viewers (gay or straight.) Indeed, while the various women in the movie generally stay clothed, Brando spends virtually his entire screen time bare-chested or sporting a suitably proletarian-looking singlet that is either at the point of falling off, or drenched in sweat.

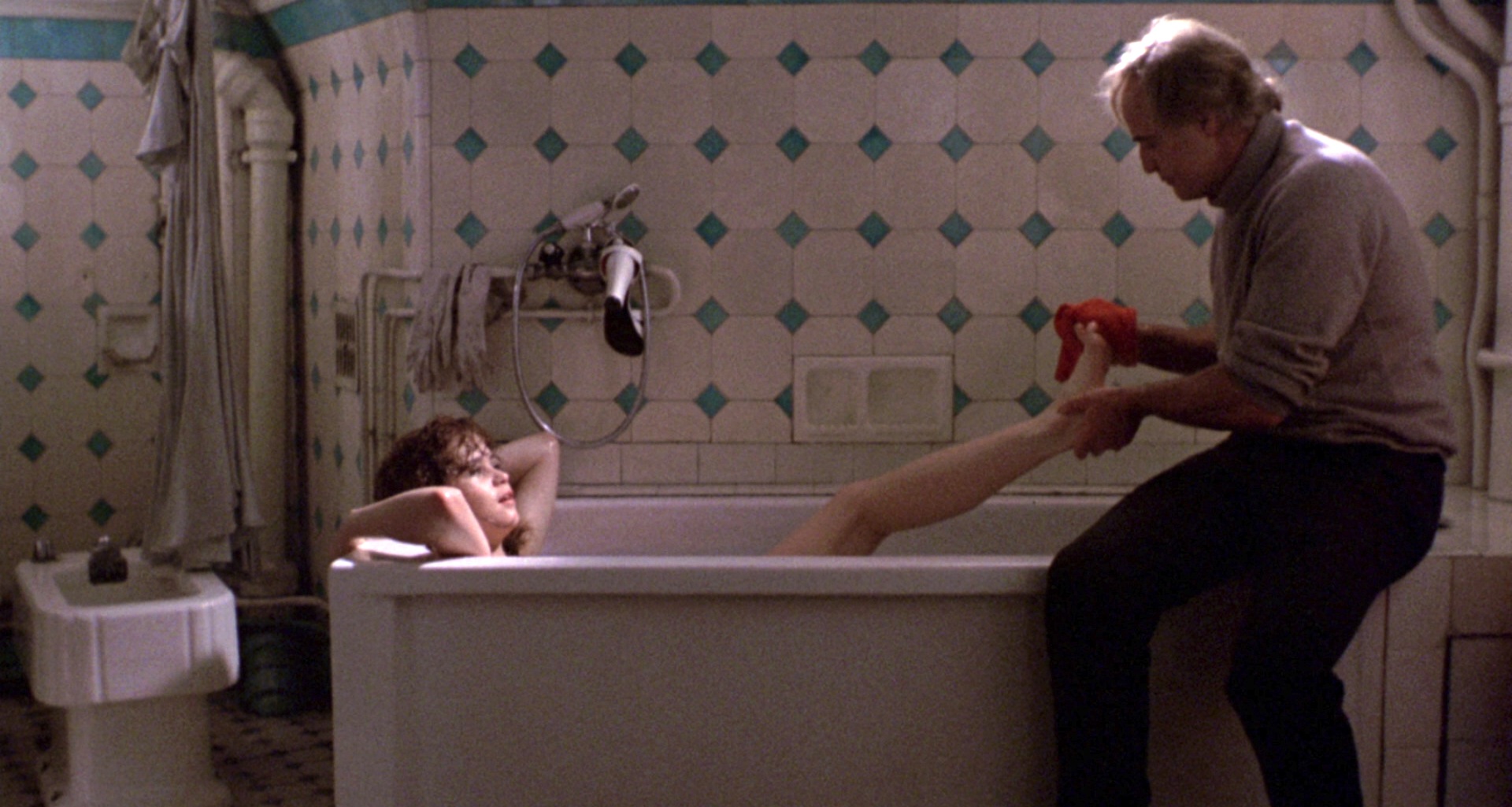

Twenty-two years later, in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972), the tables have completely turned. Carrying on the predictably misogynist style of the so-called liberated 1960s counterculture, it is now Brando who stays clothed—even during sex—while the young woman, Maria Schneider, prances naked before the camera in scene after scene. Bertolucci did, in fact, film Brando’s naked genitals, but chose to cut this apparition from the finished film, candidly admitting: “I had so identified myself with Brando that I cut it out of shame for myself. To show him naked would have been like showing myself naked.”

Why is it that Brando’s body, once upon a time such a proud object of display, ends up so cloaked and occulted, so painfully fragile under our gaze? There’s more to it than Brando’s personal insecurities—already well-developed by the early seventies—about growing old and losing his good looks. The deeper reasons are cultural, concerning the ever-shifting politics of gender. Between the brief flowering of masculine beefcake in the fifties and the lasting shame of the seventies and eighties, there lies an entire tale of the twilight of a certain kind of masculinity, at least in our Western world.

Brando, who had been a glorious monument of this masculinity, became its ghost. In the despairing cinema of the 1970s—the cinema of Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro, Brian De Palma and Al Pacino, James Toback and Harvey Keitel—Brando was several times asked to play his own phantom, a withered and inglorious simulacrum of his former youthful triumphs: thus Vito Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), Paul in Last Tango (whose fictional biography resembles a composite of Brando’s past roles on and off screen) and Kurtz in Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979).

What had happened to all the icons of masculinity in the meantime of the sixties? A few rose—Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967), Robert Redford and Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969)—but many more fell, and fell hard. Looking back from the fated meeting of Brando and Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now, one can see the poetic affinity between their respective careers. Hopper—who likewise emerged alongside James Dean in the blazing era of rock’n’roll’s youth culture—lived out all the available excesses of sixties liberation, and paid the price of fifteen years of exile in filmdom’s hinterlands, before making his mid eighties comeback with David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986).

Brando, the original Wild One, blew out in a somewhat different way during the sixties—he learned how to be lazy, and coasted through a sometimes intriguing, sometimes forgettable string of films: The Appaloosa (Sidney J. Furie, 1966), Mutiny on the Bounty (Lewis Milestone, 1962), The Night of the Following Day (Hubert Cornfield, 1968), The Countess From Hong Kong (Charles Chaplin, 1967), The Saboteur (Bernhard Wicki, 1967), Bedtime Story (Ralph Levy, 1964) and Candy (Christian Marquand, 1968). His striking roles in this period—The Nightcomers (Michael Winner, 1971), a variation on Henry James’s Turn of the Screw), The Chase (Arthur Penn, 1967), and Reflections in a Golden Eye (John Huston, 1967)—were Gothic premonitions of the ghostly, emptied-out Brando to come.

As he grew impossibly difficult on the set—he can be clearly seen in many of his later films rolling his eyes to catch a glimpse of the next cue card, as the documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991) colorfully relates—Brando came more and more to embody, within the films themselves, the figure of the difficult, troubled male, no longer fitting anywhere in a changing world. As with Hopper, it is striking to realize how little we identify Brando with love, romance, or ecstatic sexual union with a string of leading ladies. He was, in a profound way, the first Raging Bull of American cinema, in his lone anguish and frenzy.

This later became the rule for the male stars who followed in Brando’s wake, actors such as De Niro and Pacino, whose films of the seventies regularly chart the breakdown of all heterosexual and familial relationships—in New York, New York (Martin Scorsese, 1977), Cruising (William Friedkin, 1980), Scarface (De Palma, 1983), Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1976) and many others. But while these actors make sure to smuggle a modest little romance like (in De Niro’s case) Falling in Love (Ulu Grosbard, 1984) into their filmographies, once in a while, to relieve their screen personae of too much dreaded male angst, Brando simply plunged into his mid-career portrayals of the most sterile and deathly Bad Fathers ever dreamed up by a patriarchal society in decline—Corleone, Kurtz, Walker in Pontecorvo’s Burn! (1969).

Brando briefly tried to turn his image around to that of a symbolic Good Father to Matthew Broderick in The Freshman (Andrew Bergman, 1990), but his later roles, as a general rule, continue to follow the Dark Side —with an indelibly bizarre appearance in John Frankenheimer’s compellingly weird The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996) capping off the trend. In an infinitely less uncomfortable fashion, The Score (Frank Oz, 2001) gives us, in its conventional, master-thieves plot, a thinly veiled allegory for what can happen when three generations of vain, powerhouse males share the screen: De Niro testily defers to Brando, while Edward Norton keeps whining that he gets no respect.

Brando, on screen (and frequently off it, as well), represented many of the contradictions of masculinity in crisis. As Corleone, he is both a cold-hearted manager of murder and—in his last moments before dying of a heart attack—a little child. As Paul in Last Tango, he is both a celebrated, Henry Milleresque, dirty hero—willfully obscene, living beyond the codes of respectability, flaunting the materiality of his body in the face of a repressed, anally retentive world—and a brutal dinosaur of the phallocratic age, boarding a streetcar driven not so much by earthly desire as by a complicated, Freudian death-wish. (Recommended reading: the detailed socio-psychoanalysis of Last Tango in Britton on Film: The Complete Film Criticism of Andrew Britton.)

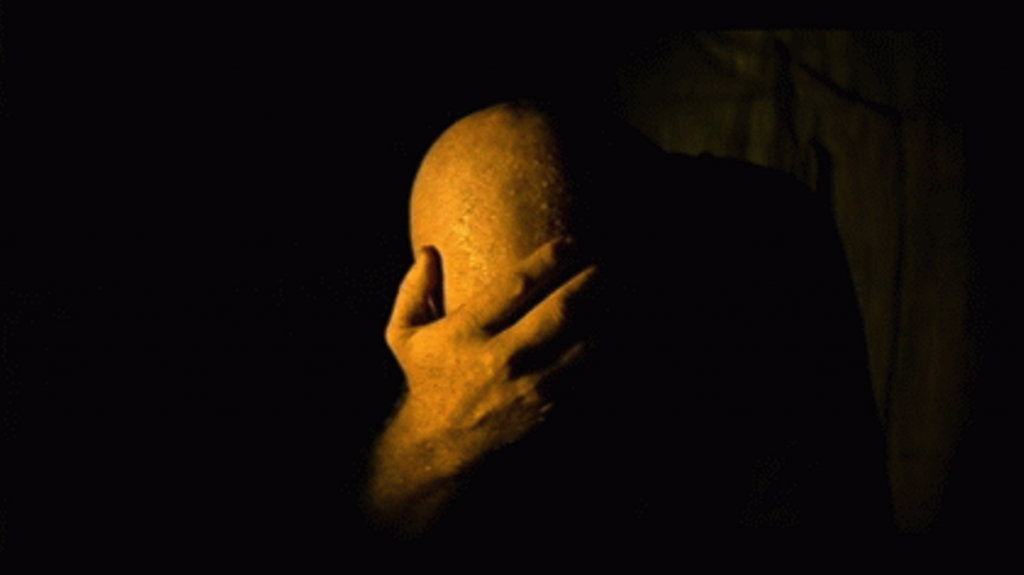

Indeed, death comes to haunt, explicitly or implicitly, all of Brando’s later performances. In Last Tango, he speaks of the necessity to go “up the ass of death and into the womb of fear,” and regularly envelops himself in a cloak of darkness—Bertolucci’s lush mise en scène meshing with his psychosexual complexes at every point. In short, Brando does not portray the revolutionary man striving, with however much difficulty, to cast off his old masculine identity and adopt a new one—like Willem Dafoe in The Last Temptation of Christ (Scorsese, 1988)—but the dying, broken man of our world, the man on his way out. And as Dotson Rader (author of Ain’t Marchin’ Anymore! An Honest Account of Life Among the Disaffected Young— Their Violence, Politics, and Sex) remarked at the time of Last Tango: “There is courage in that, and great beauty.”

What of Brando the actor? That he is often impressive, and sometimes dazzling, is beyond dispute. But I suspect that the precise nature of Brando’s performance style has somewhat escaped notice, falling as it does between two very distant schools—the Old Hollywood star school, and the ultra realistic neo-Method school. Conventionally, Brando is associated with the violent, radical break with the Old School that was ushered in by Lee Strasberg’s Actor’s Studio and the adoption of Stanislavskian Method acting on screen. But is Brando really the caricatural Method actor, powered by the interior emotions of his particular character, seeking out the truth of his performance? Brando is, in fact, not so far from the earlier classic American stars—John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Cary Grant, Robert Mitchum, Humphrey Bogart—and their concept of acting as the ability to maintain a simple but powerful presence on screen.

I would argue that Brando almost never turned in a deeply psychological screen performance. What he took from the Method, and what he pioneered in movies, was an intriguing new way of adjusting and pitching the exterior or surface of a role. (De Niro follows him in this, as does—in a kinkier vein—Christopher Walken.) The contrast with the Old School came in the way that the poise of a Bogart or Mitchum tended to be replaced by something contrivedly busier, messier, more neurotic and eccentric—hence Brando’s infamous mumbling. But his greatest moments, whether as the Kowalski, Corleone or Kurtz, are when he arrives at an inspired bit of business: playing with a glove, running his hands through his hair, adjusting his pose, clearing his throat.

Brando is the actor as showman, forever refining and modulating his schtick. This highly self-conscious, mannerist tendency in Brando’s art—often derided as a put-on, self-parodic element, but far richer than that—becomes abundantly evident in his chameleon-like role in Arthur Penn’s underrated The Missouri Breaks (1976); and in his only effort of direction, the quite strange and wonderful Western, One Eyed Jacks (1961), which he began with Stanley Kubrick but then took over. Rewatching this singular film today can make us regret all the more that Brando’s long-nurtured collaboration with Donald Cammell on a project in the late seventies and early eighties (assembled by David Thomson as the fascinating novel Fan-Tan in 2006) never came to pass.

Some of the great male actors who came after Brando, who would be unthinkable without his trailblazing—such as Sean Penn or James Woods—blended Brando’s brilliant attention to surface with a return to Method-induced depths. They may have created characters more dramatically complex (at least in a traditional sense) than anything Brando did. But Brando’s special gift to popular culture was, after all, himself as a highly perishable, masculine icon.

Another memorable, late-career moment: Don Juan DeMarco (Jeremy Leven, 1995). Brando acts with a great deal of quiet feeling in this whimsical but intense piece. The film has, among its major themes, a classic romantic comedy concern: the revitalization of rapturous, erotic love among middle-aged-and-older people. As such things get depicted in Hollywood cinema, this means that a seventy-year-old Brando gets to square off with a fifty-three-year-old Faye Dunaway, proclaiming things like: “This is a twelve round gig–and we’re only up to round three, baby!” But it’s touching, all the same.

Where Brando often contrived to keep his no-longer trim body away from the camera’s harsh gaze in his movies of the seventies and beyond, in Don Juan DeMarco he gives himself as he is, utterly relaxed, without apologies. Most reviewers, nonetheless, fixated on the (admittedly distressing) spectacle of Brando’s physical bulk. In fact, the film itself features good-natured jokes on this topic, and—most strikingly—it includes a quite extraordinary moment in which Brando (supposedly ‘in character’ as the shrink for Johnny Depp’s deluded Don, but really and clearly way out of character) gazes upon a photo of himself when he was a dashing, young star: Brando’s ghost, and Kowalski’s, too.

With seeming scant regard for his own officially recognized greatness as an actor, Brando eventually offered up his masculinity, the treasured masculinity of his time, as pure masquerade. By the time he played Dr. Moreau, he was ready to let himself be cast as a freak alongside other freaky-looking actors—Fairuza Balk and Ron Perlman—in a film where humanity and monstrosity, tenderness and fierceness, intermingle in ways that are both abject and strangely touching.

This is how Brando let us know, with whatever control of his on-screen career he could wield, that a masculinity which is all show is ultimately rather brittle—and that time will ineluctably smash it into a thousand, tiny pieces.