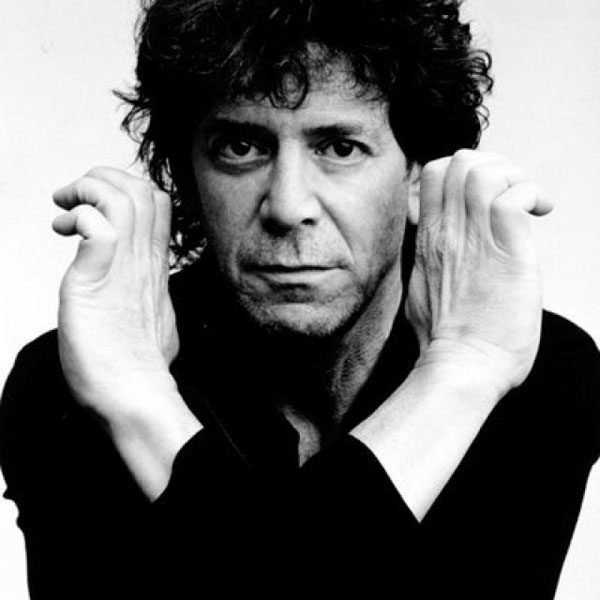

“Lou Reed, a massively influential songwriter and guitarist who helped shape nearly fifty years of rock music, died today,” reports Jon Dolan for Rolling Stone. “With the Velvet Underground in the late Sixties, Reed fused street-level urgency with elements of European avant-garde music, marrying beauty and noise, while bringing a whole new lyrical honesty to rock & roll poetry. As a restlessly inventive solo artist, from the Seventies into the 2010s, he was chameleonic, thorny and unpredictable, challenging his fans at every turn. Glam, punk and alternative rock are all unthinkable without his revelatory example. ‘One chord is fine,’ he once said, alluding to his bare-bones guitar style. ‘Two chords are pushing it. Three chords and you’re into jazz.'”

Reed is survived by his wife, Laurie Anderson, whom he married in 2008. Just a couple of weeks ago, Reed and photographer Mick Rock were promoting their new book, Transformer, a collection of photos focusing on Reed’s work in the 70s.

“Born in Brooklyn on March 2, 1942, Reed grew up on Long Island and was an English major at Syracuse University, where he was mentored by poet and instructor Delmore Schwartz,” writes Mike Barnes for the Hollywood Reporter. “He met Welshman John Cale, who played viola and had come to the U.S. to study classic music, and in 1964 they formed The Velvet Underground, with Reed’s college friend Sterling Morrison on guitar and Maureen Tucker on drums. Warhol saw them play at Cafe Bizarre in Greenwich Village and became the band’s manager. Their debut album, The Velvet Underground & Nico, released in March 1967, was radio-unfriendly and barely dented the list of the top 200 albums on the charts. Yet the avant-garde masterpiece would become one of the most influential LPs of all time, with Rolling Stone placing it No. 13 on its top 500 list in 2003. Musical innovator Brian Eno once said that while the Velvets’ first effort might have sold only 30,000 copies, ‘everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band.'”

No musician can wield that much influence over contemporary culture without some sort of overlap into cinema, and in the case of Lou Reed, there are many. Bruce Bennett reviewed one for the New York Sun in 2008: “By his own accounting, the artist and filmmaker Julian Schnabel spent three and a half decades under the spell of Berlin, the third solo album by Lou Reed, the Brooklyn-born singer, songwriter, guitar player, and Velvet Underground founder. In his new film Lou Reed’s Berlin, Mr. Schnabel has erected a cinematic monument to Mr. Reed’s 1973 musical story of amour fou between two fictional junkies clinging to life, love, sanity, and each other.”

Updates, 10/28: “The Velvet Underground made some of the most savage recordings I’ve heard,” writes Alex Abramovich for the London Review of Books, “and some of the most delicate. They sang about dislocation and distance—from society, from sobriety, from the self. Reed could be abrasive in person. But he was also the most compassionate songwriter I can think of. If Warhol flattened the characters he surrounded himself with, at the Factory, Reed breathed life back into them, ennobled them.”

The New Yorker‘s Sasha Frere-Jones: “Reed’s tendency toward structural simplicity married to noise, and a faith that no word was above his listener’s head, is at the root of so much music that I am scared to make a list, in fear of the counterlists that will point out everyone who is missing. On the Pixies’ 1987 debut, Come On Pilgrim, Frank Black sang, ‘I wanna be a singer like Lou Reed.’ That’s a fairly solid citation, so we’ve got one, for sure. We could venture further and say that David Byrne, Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus, and Ian Curtis would have thought very differently about music if not for Reed’s existence. The real list of who loved Lou Reed songs is probably something like ‘everyone,’ though that doesn’t do much for anyone looking to find something to listen to right now. His work spans my life and is woven into it, and it is impossible to imagine my own imagination without thinking of the direction in which Reed told me to look.”

Ann Powers for NPR: “Identifying Reed as an ‘aesthete punk’ whose relationship to the urban demimonde he always wrote about was intellectual, stylized and distanced, [Ellen] Willis noticed that because he also really grasped the pain of those shadowed characters he wrote about, he ended up a moralist: a writer primarily concerned with the choices that make up people’s lives, choices to hurt or help others, to be safe or potentially self-destructive, to love or to harden the heart…. What matters most in Reed’s music is the commitment to what’s difficult, whether it’s expressed through distorted guitar, lyrics whose exposure of a self or a situation peels deeper with each verse, or the kind of melodic richness that doesn’t comfort but instead renders a song’s singer vividly vulnerable.”

Carl Wilson for Slate: “For all the diversions about drugs and bisexuality and Warhol and Bowie and tantrums and feuds with the press you’re going to hear over the next weeks, what’s going to matter about Lou Reed in the end is this: his ability both in writing and in sound to wedge modes of articulation into popular music that simply hadn’t belonged there before, and with the arrogant force to make sure they stuck.”

“On the one hand, he embodied a certain kind of rock and roll attitude,” writes the Guardian‘s Alexis Petridis. “The face he presented to the world, at least in interviews, was endlessly combative, contemptuous and taciturn and you could often see that reflected in his music: the four grueling songs that make up side two of his 1973 concept album Berlin are quite astonishing expressions of coldness and cruelty. On the other, he could write songs that were impossibly moving, that spoke of a tenderness and sensitivity: the lambent, peerless ‘Pale Blue Eyes’; ‘Halloween Parade’s heartbreaking lament for New York’s gay community, devastated by Aids; his meditation on death, ‘Magic And Loss.’ He was, when the mood took him, capable of writing perfect pop songs; he was equally capable of coming up with Metal Machine Music, his infamous 1975 double album of screaming noise, still the benchmark by which all musical screw-yous must be judged and are usually found wanting. Each side of his character inspired boundless numbers of copyists. It goes without saying that none of them were really like him at all. As it turned out, one of the most imitated artists in rock history was entirely inimitable.”

More from Marc Campbell (Dangerous Minds) and Greg Kot (Chicago Tribune). Filmmaker‘s Scott Macaulay posts a batch of favorite songs; and at the Playlist, Rodrigo Perez looks back on a few cameos in films and several great movie moments featuring Reed’s music.

Update, 11/1: As you’ll have heard, Laurie Anderson has written a lovely note that’s run in the East Hampton Star. You can read Lester Bangs‘s (in)famous 1973 interview at the Guardian‘s site. And I wanted to point to just a few more remembrances: Geeta Dayal (Slate), Andrew Epstein (Poetry Foundation), Neil Gaiman (Guardian), Dave Hickey (Spin), Jim Knipfel (Chiseler), Legs McNeil (Daily Beast), and Luc Sante (New Yorker).

Update, 11/5: “As I mourned by the sea,” writes Patti Smith in the New Yorker, “two images came to mind, watermarking the paper- colored sky. The first was the face of his wife, Laurie. She was his mirror; in her eyes you can see his kindness, sincerity, and empathy. The second was the ‘great big clipper ship’ that he longed to board, from the lyrics of his masterpiece, ‘Heroin.’ I envisioned it waiting for him beneath the constellation formed by the souls of the poets he so wished to join. Before I slept, I searched for the significance of the date—October 27th—and found it to be the birthday of both Dylan Thomas and Sylvia Plath. Lou had chosen the perfect day to set sail—the day of poets, on Sunday morning, the world behind him.”

Update, 11/7: Laurie Anderson has written a beautiful piece for Rolling Stone, recalling how she and Reed met, became friends, became inseparable, married. “But when the doctor said, ‘That’s it. We have no more options,’ the only part of that Lou heard was ‘options’—he didn’t give up until the last half-hour of his life, when he suddenly accepted it—all at once and completely…. I have never seen an expression as full of wonder as Lou’s as he died. His hands were doing the water-flowing 21-form of tai chi. His eyes were wide open. I was holding in my arms the person I loved the most in the world, and talking to him as he died. His heart stopped. He wasn’t afraid. I had gotten to walk with him to the end of the world. Life—so beautiful, painful and dazzling—does not get better than that. And death? I believe that the purpose of death is the release of love.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.