An elegy is often a thought or a reminiscence of something that happened, something you want to return to but never will. Elegies are, more precisely, good memories. That is the important thing. Something that happened and that you want back, but it won’t return. Why not? Because there is death.

—Alexander Sokurov, quoted in the film Alexander Sokurov, Questions About Cinema (2008)

A man smacks his lips and tastes his own breath. It’s hot, and its odor is strange to him. He is Emperor Hirohito of Japan, incarnated by the actor Issey Ogata in Alexander Sokurov’s film The Sun (2005). The film, one of five Sokurov titles here (three of which are also included in the superb Cinema Guild home video release Sokurov: Early Masterworks), takes place towards the end of World War II, with the Emperor now spending his days confined indoors, anatomizing crabs and awaiting meetings with the American General McNamara. To all those who serve him, the Emperor is a god, but to himself, he is merely a body.

“We’ve talked a lot about the body but we haven’t yet found the soul,” says a medical assistant in Sokurov’s most recent completed feature film Faust (2011, opening theatrically in the United States in November), a line that could easily apply to The Sun. Both films are steps taken on the Russian filmmaker’s long journey in search of the soul, recently sampled in the thirty-film-and-video-works retrospective “Alexander Sokurov: Visual Poet”, organized by Fábio Savino and Pedro França for the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil locations in the cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Brasília. (Per standard CCBB practice, the freelance curators have also assembled an extensive catalogue that includes color stills, a full filmography, and critical texts and interviews with the filmmaker, many appearing in Portuguese for the first time.) But this expansive selection of works—greatly varied in running time (from shorts to feature-length works to miniseries) and genre (documentary, fiction, and experimental pieces hard to class as either)—represents only about half of Sokurov’s career output. The individual works of this artist whose soundtracks often swell with Mozart and Messiaen are themselves like musical themes, and the more of them one experiences, the more that they seem to build with resonances between them.

These resonances often circle around the problem of death—sometimes literally, as in the early feature The Second Circle (1990), in which a young man (played by Pyotr Aleksandrov) warily approaches his father’s half-glimpsed corpse at different angles within a series of fixed, dark, static frames. This problem is often countered with the suggestion of art extending or prolonging life. Most readers who have seen a film by Sokurov have likely come to him through the glowing example of Russian Ark (2002, a new DCP restoration of which will begin a New York theatrical run September 6), a sweeping one-shot tour of Saint Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum that envelops seemingly the entirety of Russian history within itself, along the way suggesting time as a force in eternal motion; “We are destined to sail forever, to live forever,” the film’s unseen narrator (voiced by Sokurov himself) says.

Sokurov’s voice often speaks from behind a roaming camera-eye, echoing his own oft-stated dictate that sound is his soul and image his legs. The journey typically taken is of awakening, beginning with a passageway from darkness into light as the narrator wonders where he is, how he got there, and to where he will soon go. Along the way a viewer senses that the unseen man is being guided, and even pushed, by forces greater than himself. In the delicate Oriental Elegy (1996), the voice moves through mists to commune with the ghosts of elderly men and women on a Japanese island, and in the process shifts from “I shall return some day. I shall return” to “And I shall stay;” by contrast, a visit to a live elderly Japanese woman, sewing a mourning kimono for her lost husband in the following year’s A Humble Life (1997) includes a small housed framed by trees and a full moon, along with the thought that “I was looking at her house and felt sure that I should never see it again.” The narrator finally leaves her home because, he says, “It is time to start on my journey”; he has begun another journey, we sense, due to the simple reason of time.

This pained sense of time passing, aware of all times and longing for former ones, has helped lead Sokurov to become what the great critic and programmer James Quandt calls (in an audio commentary included on the Cinema Guild release) “a radically experimental traditionalist.” Much experimentation has come out of the artist’s attempts to manifest the tensions between moving and frozen time, notably in his career-long efforts to make films that resemble centuries-old paintings. The images are often warped, stretched, and distorted in ways atypical for film imagery due to special lenses that have been made for the occasion. Some results can be seen in the clouds looming over the distended fields of Mother and Son (1996), recalling the landscapes of the 19th-century German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, or the way in which a fog-shrouded Japanese mountain range in Dolce (1999) echoes the Japanese style of ink painting called sumi-e. Both works feature a person holding onto the memory of a lost loved one (a son caring for his dying mother in the first case, a woman addressing her dead husband in the second), and their own positions within carefully composed landscapes represent an effort to preserve their lives before time brings an inevitable cut or dissolve.

Sokurov has stated that having multiple eye surgeries throughout his life has heightened the importance he places on finding and articulating a clear, strong sense of vision. His frequent position—as well as that of many of his characters—is one of composing a frame from within a larger frame, a position mirrored by the young male artists daubing their paintbrushes within a number of landscapes composed by one of Sokurov’s favorite painters, the 18th-century French classicist Hubert Robert. The filmmaker’s short Hubert Robert: A Fortunate Life (1999) often feels as though it is literally taking place inside several Robert paintings found at the Hermitage, as the film frame fills with distended images from them. Sokurov layers his own interests on top of Robert’s by framing the journeys through paintings with hazy opening and closing views of blossoming trees surrounding an ancient Japanese play, which ends at the same time that Sokurov’s narrator tells of Robert’s death in front of his own easel.

The viewer is often aware of the endings of Sokurov’s films well in advance of their arrival; in general, the heightened awareness of frames that his films helps emphasize the smallness of a body in the face of the greater natural world, and the brief span of life itself. In Sokurov’s painting films (which include his exploration of cherished painter Peter Saenradem’s work, Elegy of a Voyage [2001], at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam), the artworks seem to exist for the brief time that a person comes to live inside them; similarly, the filmmaker’s approach to adapting literary texts involves transforming a book into an open field through which human beings briefly roam. His adaptation of Gustave Flaubert’s novel Madame Bovary (1856), Save and Protect (1990), de-emphasizes the fantasy life of the novel’s dreamy countryside heroine in favor of frequently showing her and her lover in coitus; while Flaubert’s Emma falls upon her bed fully clothed to selfishly savor the words “I have a lover,” Sokurov’s unnamed woman (played by Cecile Zervoudaki) stands naked and speaks them while cradling her own nude infant daughter. She and her family—among them her doctor husband whose operations proceed in bloody detail—are constantly seen against the backdrop of the rocky rural area in which they live, up to and including the sight of gravediggers shoveling dirt upon the eventually dead woman’s trio of coffins while children play in surrounding fields.

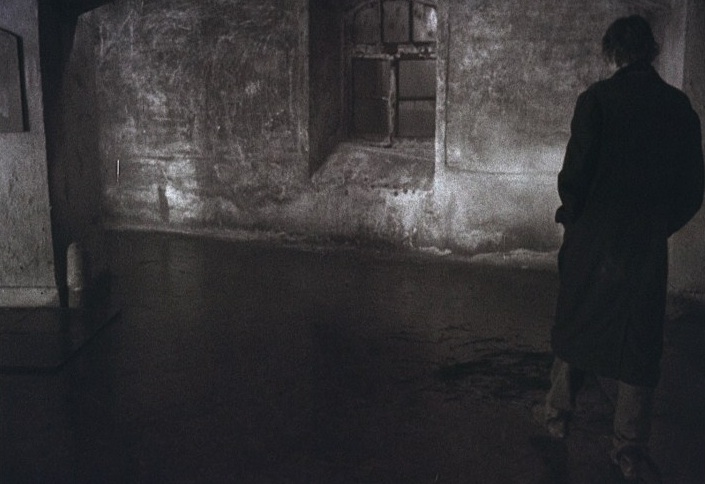

Whispering Pages (1993) opens, as do some other Sokurov films, with the leaves of a book flapping; this one in particular announces a film based on the work of 19th-century Russian writers, one of whose unnamed characters (played by Alexander Cherednik) is clearly meant to be Raskolnikov from Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866). Yet, though the young man shares Raskolnikov’s crime of having killed an old woman to prove his moral superiority, Sokurov’s figure differs greatly from Dostoevsky’s aggressively talkative man of ideas racing through St. Petersburg, instead emerging as a wide-eyed, largely quiet traveler through a green-gray, catacomb-strewn underground world. He does not need to proclaim that he is growing more alive to sensation, as Raskolnikov does, because we see this and hear it. The possibility of his remaining in the underworld—underlined by a young woman telling him, “Your hands are like a corpse’s”—contrasts with startling echoes and sudden human movements that seem to belong more to the world of the living, as the young man meets “members of the degraded and humiliated” whose humanity jolts him.

Though Sokurov’s films often move deep into meditation, they can also suddenly break their spells. They have been able to startle at least his early Mournful Unconcern (1983), a crazed adaptation of the Englishman George Bernard Shaw’s play Heartbreak House in which scenes of a brothel intermingle with mortar blasts and archive footage of carnage from the First World War. One feels constantly disrupted while watching the film, as a civilian caught in war might be. A character’s sentiment that “Modern society does not inspire respect” echoes the feeling expressed by the filmmaker (himself born into a Siberia-stationed military family in 1951) in other works of the essential destructiveness of modernity, which life at war represents. The five-part miniseries Spiritual Voices: From the Diaries of War (1994) takes place among soldiers stationed on the border of the Tadjikstan Republic during the conflict with Afghanistan, and contrasts Mozart-scored moments of lyricism in a splendid, natural world with flat, ugly video photography of the men at work, hoping to avoid death while flies buzz around them. Father and Son (2003), whose lead characters are among a group of stationed Russian soldiers, bathes bare-chested male bodies in splendid golden light to draw the viewer towards them while critiquing the military as a closed system incapable of creating new life.

Sokurov, who has said that military men are the weakest kind of people he has known. A suggestion of why is given as bright yellow light gains muddier textures at the outset of Alexandra (2007), whose title character has come to stay a group of Russian soldiers patrolling the Chechen border, including her grandson. The old woman (played by opera star Galina Vishnevskaya, a former Russian expatriate for housing the writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn and the subject, along with her composer husband, of Sokurov’s documentary portrait Elegy of Life [2006]) registers surprise at how the soldiers seem so young, to the point where they appear to have no conception of life outside the front. They act hostile with locals, from whom they keep themselves separate, and look uncomfortable setting a table for her. Throughout, the film’s soundtrack summons faint echoes of horse hooves and war cries, as though the ghosts of older warriors are still imposing themselves upon the present.

The boys belong to a tradition built upon the destruction of other traditions. Sokurov’s film sequence the “Tetralogy of Power”—which, in addition to The Sun and Faust, include Moloch (1999) and Taurus (2001)—further the domineering nature of war leads to human collapse. In each film, a once-strong military leader (Satan included) is confronted with a growing loss of power, even over his own crumbling body. The poetic short film Sonata for Hitler (1979-1989), in which archive celluloid images of the Führer flicker across a screen in a projection room, contrasts with the apelike leader (played by Leonid Mozgovoy) at the center of Moloch, who lives in exile in a castle towards the end of the Second World War. As he stands shrieking Nazi ideology in an undershirt and shorts near his bathtub, the film regards Hitler at a distance, in such a way that he immediately seems to be small, ugly, and pathetic.

By contrast, the wheezing, decrepit, blotchy invalid Lenin (also played by Mozgovoy), exiled to the countryside to live out his remaining days in Taurus, looks much more pitiful than worthy of condemnation. (By contrast, Stalin’s brief, smiling visit to the prisoner presents the current ruler in good health.) Lenin is greeted with sympathy by his wife and maid, both of whom quietly understand the leader that he once was and the shell that he now is; the old man, when he can go out, greets a world rendered in fading green, with storm clouds passing overhead. He and the older culture that he represents are bound to die, but—less like Hitler’s Third Reich, and more like Hirohito’s Imperial Japan—their loss is worth mourning.

Lenin is one of Sokurov’s many ghosts. Several such figures in other portrait films—Chaliapin, Kosintsev, Tarkovsky, and Shostakovitch among them—are phantoms of Russian culture in particular. Chekhov (played by Mozgovoy) roams the grounds of his old house in Yalta, now a museum, in the lucid black-and-white Stone (1992), encountering a young guard (played by Pyotr Aleksandrov) one night. They dine together, and then explore the surrounding roads and hillside before returning to the house. As the young man glimpses his elder’s unspoken sadness, he sees a dead man who lives rich with the memory of life. Like many of Sokurov’s other journeyers, he gives witness to both the grotesque and the sublime.

Thanks for research help to Boris Nelepo, James Quandt, and Ryan Krivoshey and The Cinema Guild.