Have you ever gone to a film and watched everyone around you helpless with laughter, while you sat with little more than a puzzled smirk on your face? If you have, you know that what’s funny can be a very personal thing. It can also be culturally specific, with a social context for humor being essential to an appreciation of the inside jokes and overall hilarity of a film from another country, generation or subculture.

One of the great divides of comedy that rarely gets mentioned these days is the differences between what men and women find funny. Comedies by women have been something of a breed apart, and rarer than other films by women, since the dawn of motion pictures. Therefore, there tend to be misunderstandings about what a female filmmaker might consider funny. Many people think the terms “chick flick” or “romcom” are the catch-alls for female-centric comedy, with an emphasis on romance. Some of the biggest commercial successes, however, have been buddy comedies made with a female audience in mind. For example, Bridesmaids (2011), written by Kristen Wiig and Annie Mumolo, resonated with many women who have had the experience of enduring the happiness of a best female friend or relative as her sidekick in going down the aisle. Nonetheless, for me, the film betrayed the directorial hand of a man (Paul Feig) in its occasional humiliation of its female characters and particularly in the toilet humor that I found more revolting than funny. Women tend to be more subtle in making people smile.

This is not to say that women do not enjoy body humor; it is just that most of us tend to have a fraught relationship with our bodies. A funny male character generally will look or be made to look peculiar to get laughs. Women, on the other hand, often feel like we look peculiar no matter how we appear to others. This insecurity explains why a very attractive actress-director like Julie Delpy has no trouble in 2 Days in New York (2012) demolishing the chic image of the French, with her crass family and dowdy clothes, and demystifying her own allure by complaining about her sagging bladder.

Women had greater freedom in the early days of filmmaking to try different voices on for size. Nonetheless, they did produce some markers of a feminine sensibility worth examining. French filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché, a director who made nearly 400 short films from 1896 to 1920, dabbled in a wide variety of genres. Two of her comedies reflect unique perspectives that female filmmakers would follow in the decades to come.

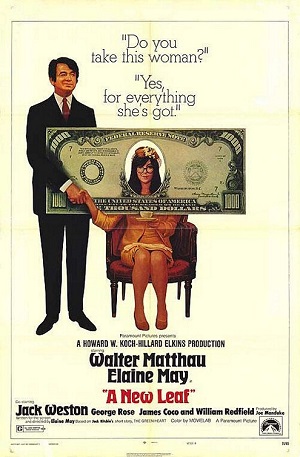

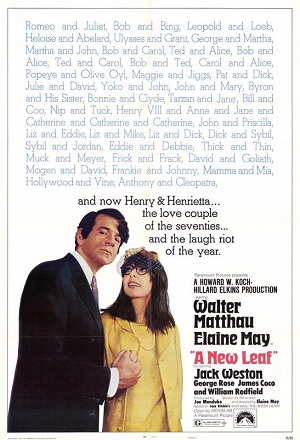

The Consequences of Feminism (1906) avoids one male-oriented version of role reversal—dressing in drag—by actually reversing the behavior of men and women. The women, still wearing floor-length dresses, hang out in bars drinking, smoking, and avoiding their menfolk. One unfortunate husband comes into the female-only bar with two small children in tow to beg his wife to come home and take care of them. Men cower from women who try to chat them up aggressively on the street and shrink from the fist fights the women are only too happy to start. The film provokes laughter by confounding the expectations of the audience, but goes much further in imagining a completely different social order. Looking ahead to Elaine May’s A New Leaf (1971) shows a variant on role reversal, with May playing a rich, absent-minded professor to Walter Matthau’s fortune hunter who shows a flair for domestic management.

Guy-Blaché’s The Drunken Mattress (1906) is an example of physical humor with a certain understatement not often found in silent comedies. A portly couple calls in a seamstress to restuff and sew their flattened mattress. She carries the mattress to an open field , opens it up, restuffs it, and then pops into a chocolatier for a hot chocolate. A drunk wanders near the mattress, hops on it to take a snooze, and covers himself with the open flap. The seamstress sews the flap down, and the rest of the film depicts the seamstress’ travails carrying a very lively mattress back to its owners.

The Drunken Mattress takes a simple premise, and rather than run amok with it, finds humor in the every day. There are no great feats of derring-do or dexterity as one would find in films by Charles Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, or Buster Keaton, thus offering the world a vision of humor not based on physical prowess or strength. Guy-Blaché’s grounding in the domestic industriousness of the hapless seamstress plays with the possibilities for comedy that can be found in a woman’s world. Moving forward, Vera Chytilová’s Daisies (1966) offers keen physical comedy that has its central protagonists, two sisters, set fire to their home and make subversive mischief with their feminine roles of nourisher, love object, and good girl. A New Leaf, again, offers ordinary physical comedy in place of spectacle; for example, May and Matthau’s characters gets guffaws as he tries to extract her head from the armhole of an off-the-shoulder toga.

Comedies by and about women that are largely unlinked to romance are relatively rare. They are not terribly concerned with being broadly comic, relying more on the subterfuge women have had to engage in to make their way in the world and indulging in wish fulfillment in asserting an equal place for women in society. When physical, a woman’s way with comedy tends to be smaller and more true to life. In focusing on the common experiences of women, such films can provide valuable information to outsiders looking in.

Marilyn Ferdinand is a freelance writer and regular contributor to Fandor. She blogs on film at Ferdy on Films and is the cofounder of For the Love of Film: The Film Preservation Blogathon.