On July 1, 2008, a young man murdered six policemen at a Shanghai police station. He was subsequently tried and then executed that November, during which time his case seized much of China’s public imagination. Though court proceedings were closed, details about the twenty eight-year-old Yang Jia eventually emerged: He had been detained and beaten by police the previous year for riding an unlicensed bicycle, and his multiple subsequent legal petitions for redress had been ignored. Assaulting the system finally made it pay him more attention.

News also eventually came out that his mother, Wang Jinmei—who had worked closely with him on his petitions—had also been detained by police on the day of the attacks. Furthermore, her name had been changed and she had been sent to a mental hospital, where she was released from confinement after 143 days. For much of that time, she did not know what had happened to her son. She did not learn of his death until after it had taken place.

Ying Liang’s film When Night Falls shows the day of Yang Jia’s death from Wang Jinmei’s point of view. Ying (who was born in 1977) made the film for last year’s Jeonju International Film Festival’s Digital Project, and it will receive its New York premiere May 24 as part of the Museum of Modern Art’s series Chinese Realities/Documentary Visions, a large survey of recent trends in Chinese independent documentaries and documentary/fiction hybrids co-organized by Sally Berger and Kevin B. Lee. When Night Falls opens and closes with photographs of the real Yang Jia and Wang Jinmei taken from her blog; in between, the actress Nai An plays the woman as she learns about and reckons with the execution. Many of the film’s scenes are rendered starkly, with a fixed camera and harsh lighting presenting Wang Jinmei alone in her apartment. As she silently tends to a plant, a dreadful sense of waiting sinks in. The film captures moments in the life of an isolated, trapped person.

“Ying’s earlier films were more exploratory in content, form and perspective,” says New York University (NYU) Professor Zhen Zhang, who has organized screenings of several of Ying’s films through the series Reel China (a valuable showcase for important recent Chinese films, co-organized with NYU Professor Angela Zito). These include The Other Half (2006), whose lead character (played by the actress Zeng Xiaofei) works as a clerk at a law firm; the staged scenes of her daily life alternate with documentary-style interviews with a variety of people who voice their unresolved legal problems to the camera. As Lee discusses in his Keyframe video essay on The Other Half, the film’s fictional frame creates an occasion to see and hear people who might never otherwise receive public recognition.

Ying, who has endured police threats as a result of making When Night Falls, has referred to a key function of filmmaking (whether documentary or fiction) as “artivism,” in which creative thinking leads to public action. “Ying’s recent films more directly intervene in social realities,” continues Zhang, a friend of the filmmaker’s who gave support and advice throughout When Night Falls‘s creation. “But they also simultaneously search for new hybrids of expressive and narrative idioms.” The Other Half’s approach differs from that of the short fiction film Condolences (2009), made in response to a 2004 bus accident in which 15 people were killed and 39 wounded. The bulk of the movie consists of a single fixed shot containing the small figure of a seated elderly woman whose son and husband died in the accident. The local mayor and his entourage ritually express their sorrow to her, as does a news reporter hungry for an interview. The woman’s back stays to the camera throughout; the film recognizes her suffering while suggesting that it exists beyond direct representation.

Despite their different presentations, Ying’s films share a need to lend human faces to dehumanizing situations. These faces include the filmmaker’s. The Other Half, Ying’s first feature (Taking Father Home, 2005) and his third feature (Good Cats) all open with a person seen in direct address with the camera, creating the impression of stories that will be told from his sympathetic perspective. Similarly, words from an interview with Wang Jinmei (spoken by Nai An) are heard in voiceover as the photographs of her and Yang Jia appear at the beginning and end of When Night Falls. The still photographs represent how this woman wishes to be seen, and the reenactments in between them represent how the filmmaker sees her.

Keyframe: When Night Falls is dedicated both to Wang Jinmei and to your mother. How is your mother important to the film?

Ying Liang: When I was eleven, my father was taken away for political reasons. For about three years it was very difficult for him to contact our family. During that time, there wasn’t an official reason given to us for his disappearance. But even though I didn’t understand it, I saw my mother doing things to try to save him. I saw her difficulty, her exhaustion, her bravery, and her positivity. I felt something similar from Yang Jia’s mother, including the confusion that comes from not knowing what you’re supposed to do when your closest person is taken away from you.

My mother didn’t know that I was going to make this film, but there are memories and impressions that I had of her that helped me make it. There were also some things that happened during the production that were related to her, none of them planned. For example, the city that this film was made in was Shenzhen. My mother grew up in the North. But when I was looking for extras, I found a person who went to high school with her. So I thought that this was some sort of sign.

Keyframe: How did you find the film’s story?

Ying: The path was very personal, and I felt like it was planned for me. My family’s in Shanghai, and I rarely go back. But on July 1, 2008, I went. That was the same day that Yang Jia attacked the policemen at a local ward of Zhabei Police Division. The place where I got off the airport shuttle bus was right across the street. It was only a few hours after the incident, and I saw many police and many bystanders. My home was one bus stop away. My maternal grandmother used to work in the police division board, and when I was in junior high school, I used to stay in that board waiting for her to finish work. The attack happened in a newer building than the one I went to when I was younger, but I still felt pretty close to the place. I felt like this event was related to me, and I thought that I could feel how this young man felt.

After that, I kept watching. I followed the judiciary process and absorbed a lot of the problems. The judiciary process was not open to the public, so most of the media professionals couldn’t describe why Yang Jia wanted to commit these murders. Their description of him as a person was unified, though—he perhaps had some psychiatric problems, and some personality issues. His family situation, including information about his mother (whom no one knew how to find), was not questioned, and there was no way of investigating it. Yet during the process the artist and political activist Ai Weiwei kept a blog where he was posting questions. Ever since Yang Jia was beaten by the police, Ai Weiwei had been asking that information be publicized. Later, during the judiciary process, he posted that he was searching for Yang Jia’s mother. Ai Weiwei then came out with two documentaries in 2010 in which he introduced many facts and details related to the case. The first, One Recluse, focused on the judiciary process itself, and showed clearly how some lawyers had been blocked from it. The second, Wang Jinmei, interviewed Wang Jinmei. She described some of the conflicts her family had had before Yang Jia attacked the policemen, and the details of how she had been illegally detained for five months afterwards. His mother’s situation struck me, and what struck me most was that the day her son died, she didn’t know. Someone told her afterwards.

The factual information in my film comes from these two documentaries, as well as from Ai Weiwei’s blog and from other media outlets that were able to interview Wang Jinmei and provide more open information a few years after the murders. I also relied on what she had written on her blog and tweeted. During the World Cup in 2010, she would tweet match results to Yang Jia. This was very touching to me, and I felt like that sort of personal expression could make people interested in her situation.

I later learned that Nai An, the actress playing Wang Jinmei in my film, could also relate. She produced the director Lou Ye’s controversial film Summer Palace (2006), and was forbidden to work for five years as a result. Her family was divided during the Cultural Revolution. She is the mother of two children, and when we discussed the film she gave me a lot of information related to her relationship with her own mother. The film contains her views as well as mine.

Keyframe: Why and how did you choose to tell the film’s story so tightly from one character’s point of view?

Ying: This is really the most difficult film I’ve ever done. It was difficult from the start, when I was writing the script. First of all, this was a very sensationalized news event. But I wanted to make a fiction film. How could I make a film that did not hurt the facts or the people involved with them while still giving my own representation? So in writing the script, I faced a decision: I could tell an altered version of a real story, or a fictional story projected onto a real one. I decided to make the second, because I felt that from an artistic point of view, it would be more powerful to describe than to present.

I tried hard to communicate with Wang Jinmei in order to figure out what her emotional state had been. This was very difficult, for several reasons. Her image had already been depicted in public frequently and in a lot of detail, yet it is hard to understand someone complex. At the same time, I had to keep my distance from her, because if a person producing a fiction becomes close friends with the person he or she is fictionalizing, then he or she loses the individual point of view. But I really held a deep love for this mother.

The emotional process of making the film was difficult. I struggled between the real Wang Jinmei and how Wang Jinmei was portrayed in this film, and between how real events had happened and how this film was depicting them. I had to—similarly to how a documentary filmmaker would—respect the truth of what happened and respect Wang Jinmei as a person. I felt that this was a moral duty. And yet what I also had to do, as most fiction filmmakers would, was to use images and sounds to help people relate to how Wang Jinmei felt. My cinematographer, Ryuji Otsuka, is a Japanese man who has lived in China for a long time and directed a number of documentary films there. He was constantly helping me find an emotional relationship between the camera and the character through color and lighting choices that could reflect Wang Jinmei’s situation. A fiction film can create its own expressionistic value. He, Nai An, and I found this value by putting together the images we had in our hearts of a mother.

Keyframe: What role did you want the opening and closing still photographs to play?

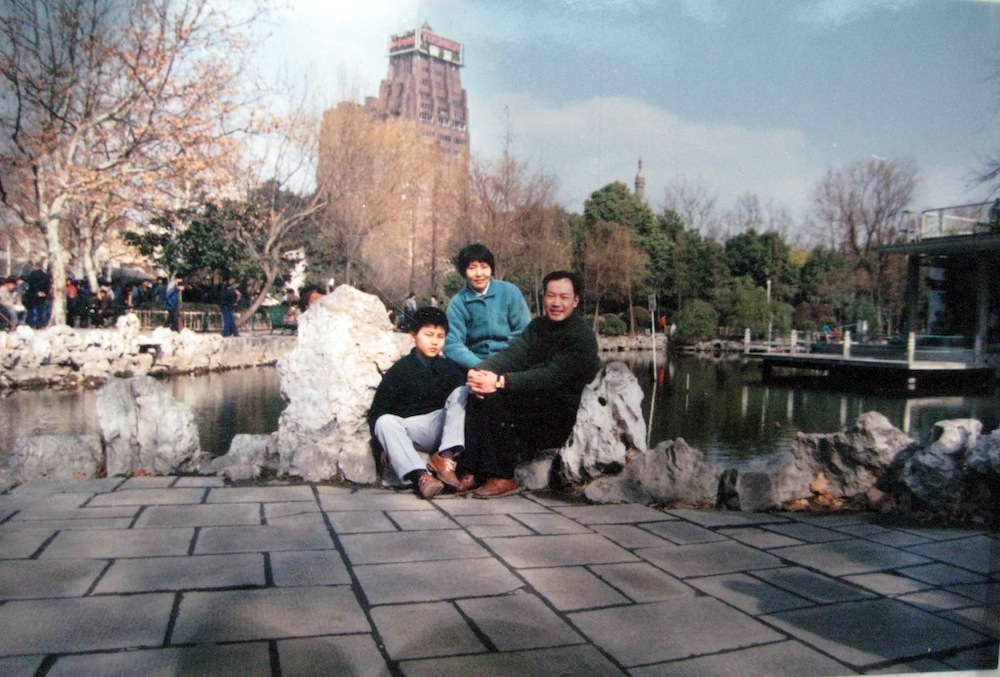

Ying: I wanted them for two purposes. The first was functional, in order to provide some basic background information. The second was to give the audience a kind of stiff, rigid social feeling—to give the impression that this is a film one has to deal with, and from which one cannot shy away. I liked the contrast that they created with the voice that Wang Jinmei was given in the media at the time. The photographs at the end were taken by Wang Jinmei herself. She would take a photograph each holiday whose contents were similar. It would either be at her home or at Yang Jia’s tomb, with some food in front of a picture of him. She would add a caption stating what holiday it was and how old he would be. She has been taking these pictures and uploading them onto her blog over the past four years. In her heart, her son didn’t leave. He is still living with her.

Keyframe: There are a few references in the film to ‘netizens.’ Why was it important to make reference to them?

Ying: I think that 2008 was the time when people online really started to be politically conscious. Even though there were not as many blogs then as there are now, a blog such as Ai Weiwei’s held a lot of influence over how people viewed public events. 2008 was a special year for China. There was a major earthquake in the first half of the year, followed by a major snowstorm. Summer brought Yang Jia’s incident, followed by the Beijing Olympics. A lot of people feel that if there had been more blogs then, some things might be different. For example, there was a lot of confusion after the Wenchuan Earthquake in terms of organizing relief effort, so more blogs might have changed that. There was also the investigation into Yang Jia’s case. Those two events were starting points for people who had perhaps not previously been as interested in political events.

The Internet was really a focus of Yang Jia’s case, and has remained so until today. There was a report on a blog just a few months ago of a Japanese man who lost his bicycle and received help from police in finding it, and people online would put the Japanese guy’s picture and Yang Jia’s together and say, ‘It’s similar. How can this event and that one be so different?’

Keyframe: Why is there a Robocop 3 poster on Yang Jia’s door?

Ying: That’s a very interesting thing, because he did have that. I did remember that image when I saw it in Ai Weiwei’s documentary. I put the poster in my film in order to respect the truth, but also, I guess, because that’s one of my images of Yang Jia. There are still people on the Internet who write poems and songs for him and praise him. Yang Jia had a special image on the Net, with people presenting him as though he were an ancient martial arts hero who had assassinated corrupt officials. I cannot use one sentence to state my personal image of him. If I had to describe it, I would say that I think he was just a regular young man in China who wanted to be treated normally, and that he was an ordinary person more than he was anything else.

Keyframe: Who do you hope will see the film? And what good do you hope the film will do?

Ying: It’s very difficult to say. The part of the story that struck me most was the emotion felt by this person in this extreme situation, in which you feel that you have something to say but don’t have a way of saying it. I know a lot of people who have had similar experiences. I knew this was not going to be a pretty film. It wouldn’t be nice to watch, and I’m now in a bizarre situation, because I actually feel that there wouldn’t have been much interest in the film without the Chinese government’s reaction to it. It would have been just like my previous films, which were very low-budget digital productions with small audiences made up of the few people who had the patience to finish watching them. Because my films never went through the Chinese examination system, they were never screened in public theaters. So this makes it very interesting to have the police break into my home and say that I had made a problematic film—I had never even really seen myself as a filmmaker before. Yet their actions confirmed that I was a filmmaker, and that I had really made this film.

Wang Jinmei saw the film and felt that, even though it was not a true documentation of her life, the character’s state was similar to hers. What I did in this film, and what I also did in my previous films, was to talk about my inner feelings. I’ve never made films to gain a wide audience. I want to make these films so that people who have had similar experiences might be interested in looking at them. Because this film and my previous films were, for distribution reasons, intended for smaller audiences, they might not necessarily reach the people that I was describing, but that isn’t something that I can personally do much about. Since I made the decision that the film would be a personal expression, very little of my attention has gone towards how many people have watched it. Yet each time I have seen it play, regardless of whether through an international film festival or just through being shown to people around me, people give me the feedback that they can feel the emotions that this mother was feeling. And to me that’s already a lot of encouragement.

This interview was conducted at the 2012 edition of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), where When Night Falls screened as part of the festival’s Wavelengths program. Alexandria Feng translated Ying Liang’s answers.

All images in this article come courtesy of Ying Liang. Thanks to Wai Ho for additional research help.