Via Alison Willmore comes word that the family of Ray Harryhausen has announced that the visual effects pioneer has passed away today in London at the age of 92:

Steven Spielberg, James Cameron, Peter Jackson, George Lucas, John Landis and the UK’s own Nick Park have cited Harryhausen as being the man whose work inspired their own creations.

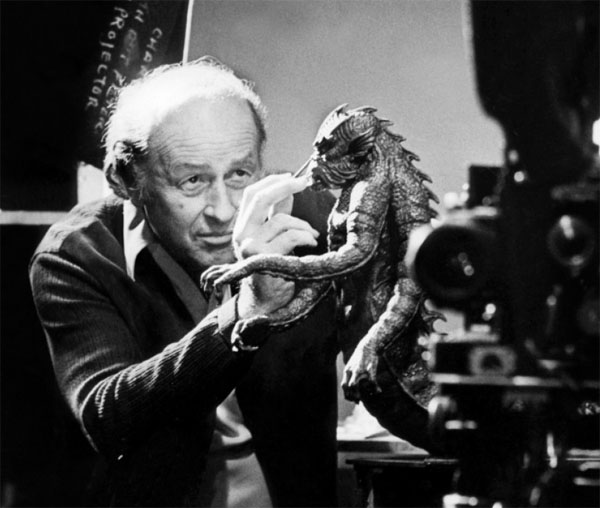

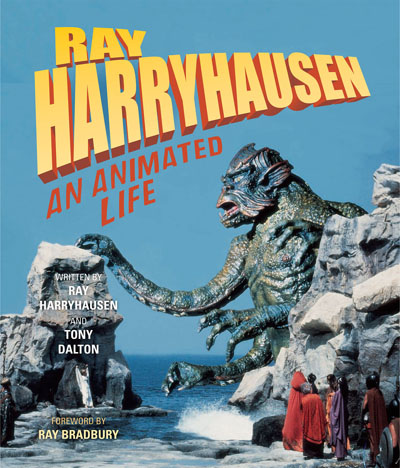

Harryhausen’s fascination with animated models began when he first saw Willis O’Brien’s creations in King Kong with his boyhood friend, the author Ray Bradbury in 1933, and he made his first foray into filmmaking in 1935 with home-movies that featured his youthful attempts at model animation. Over the period of the next 46 years, he made some of the genres best known movies—Mighty Joe Young (1949), It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), Mysterious Island (1961), One Million Years B.C. (1966), The Valley of Gwangi (1969), three films based on the adventures of Sinbad, and Clash of the Titans (1981). He is perhaps best remembered for his extraordinary animation of seven skeletons in Jason and the Argonauts (1963) which took him three months to film.

And here’s a clip from that film’s most famous scene:

In the summer of 2010, on Harryhausen’s 90th birthday, I posted a roundup of appreciations to the Notebook, including one from John Landis: “The 7th Voyage of Sinbad [1958], which became a tremendous box office success for Columbia, was the first color movie he worked on, and he was credited as an associate producer. That is an important moment in the history of the movies: Harryhausen, a below-the-line special effects technician, had become his own genre. In fact, Ray is truly unique in the history of movies as a special effects technician who is really the auteur of his films. The stop-motion creatures and vehicles Ray created were not only the stars of those movies, but the main reason for them to exist at all.”

The Guardian‘s posted a photo gallery, but to really lose yourself in Harryhausen’s worlds, head to the official site, where you’ll find a full biography, tributes, and much more.

Updates: In 2003, the Guardian ran an extract from Harryhausen’s memoir, Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life, co-written with Tony Dalton. “Greek and Roman mythology had never been my favorite subject at school,” begins the excerpt, “but as I grew older I began to appreciate the legends and to realize that they contained a vivid world of adventure with wonderful heroes, villains and, most importantly, lots of fantastic creatures. In the late 1950s, the producer Charles H. Schneer and I discussed filming a Greek legend. Between us we read all of them and decided on Jason and his search for the Golden Fleece. This would allow us the most flexibility for high adventure and fantasy. So it was that what would be known as Jason and the Argonauts was born, and of all the films that I have been connected with, it continues to please me most.”

The compilation below comes from the Stranger‘s Paul Constant, who adds: “I’ve yet to see a digital monster that impresses me the way a good Harryhausen creature impresses me.”

From Variety: “‘Without Ray Harryhausen, there would likely have been no Star Wars,’ said George Lucas this morning. ‘His patience, his endurance have inspired so many of us,’ stated Peter Jackson. ‘What we do now digitally with computers, Ray Harryhausen did digitally long be4 but without computers. Only with his digits,’ said Terry Gilliam via Twitter.”

Calum Marsh at Film.com: “Cherishing Harryhausen’s now antiquated stop-motion animation techniques isn’t a matter of mere nostalgia for some outdated facet of movie history—the quality of the work speaks louder than that. It’s true that many of the fantastic creations for which Harryhausen was responsible have aged and look dated, maybe even quaint, but they don’t look dated in the same way that, say, the early computer effects plastered throughout Tron do. Digital effects have a tendency to fall into what seems like instant obsolescence, where even the most-cutting edge images are outpaced the moment they arrive, making year-old blockbusters seem clunky and decade-old ones to look practically archaic; the advances are so sudden, the achievements so fleeting, that what’s once-revelatory rapidly becomes an antique. But Harryhausen’s effects never had that problem: their style was so singular, their presence on screen so wonderful and strange, that even today they don’t appear old-fashioned so much as otherworldly.”

From the BBC: “‘I loved every single frame of Ray Harryhausen’s work,’ tweeted Shaun of the Dead director Edgar Wright. ‘He was the man who made me believe in monsters.’ The veteran animator donated his complete collection—about 20,000 objects—to the National Media Museum in Bradford in 2010.

David Cairns: “We can be grateful that he lived long enough to see that his films lasted and were still loved and his artistry was appreciated.”

“Thank you for providing me with a place to go as a child when I needed to escape into your fantasies.” J. Hurtado to Ray Harryhausen at Twitch.

Mike Bracken at Movies.com: “For another touching tribute to the legend, check out this video of lifelong friend Ray Bradbury celebrating the career of Harryhausen back in 2010”:

“There’s a moment in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park sequel The Lost World when the T. Rex scratches itself that is a direct homage to something that Harryhausen would often have his dinosaurs do,” writes Drew Taylor at the Playlist. “The magic of Harryhausen’s monsters is that he really did fill them with personality and tics—things like that dinosaur scratch—that elevated them from some otherworldly menace to a true character. This is why he was in such demand—his creations had weight and heft, both physical and dramatic.”

“Though his on-screen credit was often simply ‘technical effects’ or ‘special visual effects,’ Mr. Harryhausen usually played a principal creative role in the films featuring his work,” writes Patrick J. Lyons in the New York Times. “He frequently proposed the initial concept, scouted the locations and shaped the story, script, art direction and design around his ideas for fresh ways to amaze an audience…. To make The Three Worlds of Gulliver (1959), which required combining footage of giant and tiny live actors in the same shot, Mr. Harryhausen went to Britain to take advantage of the ‘traveling matte’ system developed by the Rank Organization, and then decided to live and work there permanently. He met Diana Livingstone Bruce, a descendant of the Scottish explorer David Livingstone, and married her in Britain shortly after completing Jason and the Argonauts in 1963. She survives him, along with their daughter, Vanessa.”

“In Pixar’s 2001 animated feature Monsters Inc., a Monstropolis restaurant is named after Harryhausen,” notes Dennis McLellan in the Los Angeles Times. “Robert Rodriguez’s Spy Kids 2: Island of Lost Dreams included a Harryhausen-inspired multiple-skeleton swordfight and a closing-credit thank you to Harryhausen. And Lucas’s Star Wars: Episode 2—Attack of the Clones featured a gladiator-style scene, including two shots set up exactly like ones Harryhausen devised for his 1958 classic The 7th Voyage of Sinbad…. ‘Some people think it’s childish to do what I’ve done for a living,’ Harryhausen told the Toronto Sun… ‘But I think it’s wrong when you grow to be an adult to discard your sense of wonder.'”

A 1974 interview

Updates, 5/8: Guillermo del Toro, as quoted by Geoff Boucher for EW: “I lost a member of my family today. A man who was as present in my childhood as any of my relatives…. To my generation, and to every generation of monster lovers to come, he will stand above all. Forever.”

Patton Oswalt, as quoted by C. Edwards at Cartoon Brew: “If I believed in God, I’d want him to be like Ray Harryhausen—nudging us one frame at a time toward the sublime & fantastic.”

“It is fascinating that Harryhausen’s two closest childhood friends, Forrest J. Ackerman and Ray Bradbury, would themselves become ambassadors of the fantastic in the realms of magazines and literature respectively,” writes Glenn Kenny. “The triumvirate had an incalcuable impact on the pop imagination. What Harryhausen did with clay and plastic and a stop motion camera still constitutes the most dazzling and awe-inspiring body of visual effects a single filmmaker can lay claim to. Even once you knew the rudiments of how stop motion animation was done, what Harryhausen accomplished was unfathomable. The combination of his deep understanding of the frightening and the grotesque (as intuited via the Greek myths from which he drew so much inspiration), and his painstaking draftsmanship, and his literally saintly patience yielded cinematic miracles.”

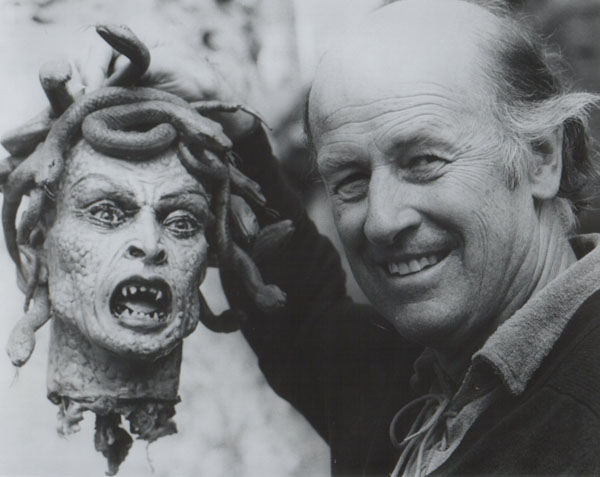

“Even when Harryhausen’s creatures do naughty or nasty things, they’re never really the enemy,” writes Stephanie Zacharek in the Voice. “The Cyclops from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) looks dumbfounded when his chest is pierced with an arrow—it’s all too easy to read the expression in his one good eye.”

Sheila Whitaker in the Guardian: “Once, when asked if he had a favorite among his creatures, Harryhausen replied: ‘It would be Medusa. But don’t tell the others.'”

“While stop-motion was discovered, CGI (computer-generated imagery) was invented, and has still to be perfected,” writes Brendon Connelly. “Cinematography is about putting something in the way of some light and using a lens to capture and focus that light as it bounces back. That goes unchanged with stop-motion, as well as any kind of puppetry, men in suits or miniatures. Everything we’d call ‘practical effects’ has actually been filmed, not just as though real, but actually for real. But this isn’t true of CGI. It requires computer software to fake what the light and the lens do naturally, and as clever as it’s getting, it’s all still an approximation…. I met Harryhausen once, at the launch of the London Film Museum’s exhibit of his works. As we chatted, he picked up one of the skeletons from Jason and the Argonauts, and—try this one, Pixar—placed his beloved creation in my trembling hands. I felt that like a bolt, I can tell you.”

Also in the Guardian, art critic Jonathan Jones: “He was a visionary who depicted the ancient myths for a modern audience: the 20th century’s answer to artists such as Piero di Cosimo, J.M.W. Turner and Gustave Moreau, who painted intense renditions of the mythology of the ancient world.”

Updates, 5/10: Adam Gopnik for the New Yorker: “What was odd about Harryhausen’s work was that it was obviously ‘fake,’ fabricated—even in its heyday, its invented, articulated falseness was as evident as it was bemusing. One wasn’t convinced by his skeleton warriors; one was amazed by them, a different thing…. There are, one might say, two theories that attempt to explain the spell his movies still cast despite their obvious deficiencies as illusions. One, which one might call the Whig version of F/X history, is that, though long surpassed by Star Wars-style miniatures, and then by C.G.I., they did look persuasive in their day, and we honor them, so to speak, as we honor ancient Roman orators: we’re not persuaded now, but we’re impressed by the persuasiveness they once possessed. The trouble is that we don’t really appreciate Harryhausen’s movies archivally, any more than we appreciate Georges Méliès’s silent magic archivally; we appreciate them poetically, not for what they did given what they didn’t have, but for what they did with what they did have.”

“Harryhausen was no fool,” writes Michael Atkinson at Sundance Now: “once the ‘80s got going, and stop-mo methods approached market obsolescence, he retired rather than pollute his pantheistic biosphere with slicker technology. Studies in an alternate physical truth of a kind only old-fashioned celluloid cinema can muster, Harryhausen’s movies should be required viewing for anyone under 12, the topsoil of whose imaginations have been desertified in recent times with the vigorous application of even more digital-screen sandblasting.”

“As a modern pioneer of the screen effects, only 2001: A Space Odyssey‘s Douglas Trumbull held a candle to him,” writes David Jenkins in Little White Lies, “and both were united in their desire to exploit the vast potential of tactile materials and (one imagines) extreme patience in being able to transport film audiences to times, world and galaxies that had never been seen before. Or if they had, never in this way.”

Updates, 5/11: “Though Harryhausen had been retired from filmmaking for decades, his death feels not only like a loss in the ongoing war between the art of the handcrafted and art by committee, but an insuperable separation from a totally different, more innocent ethos in fantasy moviemaking,” writes Nick Pinkerton at Sundance Now. “After a childhood filled with Bulfinch’s Mythology and Harryhausen’s 1981 Clash of the Titans, I was professionally obligated to see the 2010 film of the same title, starring Sam Worthington, if indeed Sam Worthington can be said to star in anything…. In one scene…, Worthington, in the armory and preparing to go a-questing, picks up a mechanical owl. Viewers of the Desmond Davis/Harryhausen movie will recognize this as Bubo, the familiar to Harry Hamlin’s Perseus, provider of a bit of kid-friendly, capering comic relief. ‘What is this?’ Worthington asks of Bubo; ‘Just leave it,’ he’s told, and the little guy is never heard from again. It’s a smirky little ‘This ain’t yo’ parents’ Clash of the Titans‘ moment, and it’s pretty much indicative of everything that’s wrong with the self-consciously edgy attitude that is ubiquitous now, everything that’s wrong with the world in general. And yet, and yet—isn’t it is a slippery slope, assigning a price above rubies to the toys and trinkets of one’s youth, acting as though the pop culture that happened to be preeminent during one’s childhood is the end-all be-all of pop culture? Isn’t much of our present morass attributable to an inability to put aside childish things, a compulsion to dig them out of storage and splash them across the screen?”

“The life he gave his creatures exists in a kind of hyper-reality, their movements more dynamic than mere organic motion,” writes Jed Mayer at Press Play. “Though given a distinctly 1960s American brand name, Superdynamation has much in common with a visual effect that is quite ancient, one dubbed the ‘uncanny’ by Freud. The hair-raising frisson of the uncanny is experienced ‘when there is intellectual uncertainty whether an object is alive or not, and when an inanimate object becomes too much like an animate one.’ One need only mention the idea of a ventriloquist’s dummy coming to life to convince us that Freud was on to something here. Doors screeching, windows rattling, shadows moving: these are all stock elements of gothic terror, but there is something uniquely creepy about the ‘too much like’ animation perfected by Harryhausen.”

“Ray Harryhausen kept multitudes from putting away childish things,” writes John McElwee. “He made it OK to go on admiring Sinbad and giant octopi. There was room for awe in adulthood for quality his work represented. You could be grown up and still want to make playroom monsters move just like magician Ray. If childhood had left us only The Magic Sword and Jack the Giant Killer, both imitators of the RH brand, it would have been easier to pack up youth and not look back. Remember when Tom Hanks gave Harryhausen a special Academy Award and said, Never mind Citizen Kane … Jason and the Argonauts is the Greatest Movie Ever Made? Nobody laughed or thought him infantile, Jason by then representing a mythology as persuasive as that it dramatized. RH was a behind-camera Zeus for 1963 watchers and ones to come.” McElwee also wrote about Harryhausen in 2010.

Sean Axmaker writes up his “ten picks for celebrating the legacy the ray Harryhausen, one of the great dreamers of the movies. Most of these, by the way, are only available on disc, so please, give a little love to your friendly neighborhood video store.”

Updates, 5/13: “He was not the originator but rather the exemplar of stop-motion animation,” writes Tim Lucas. “He took a scientific principle and gave it a consistency and character that was never-before-seen yet part of an essential tradition of storytelling traceable to the earliest etchings on cavern walls, when stories were brought to life by flickering candlelight rather than a rattling neighborhood movie projector. For the Baby Boomer generation, Ray Harryhausen was Mother Goose, the Brothers Grimm, La Fontaine and the Arabian Nights all rolled into one, himself animated by a heart of adventure whose depth and scope were worthy of H. Rider Haggard.”

In an appreciation at Indiewire, Gareth Edwards, whose Monsters (2010) was pretty much produced on his laptop, recalls meeting Harryhausen, the man who inspired him to get into visual effects: “I was just making chit chat, but it happened to be the week that the trailer for [Peter Jackson’s] King Kong [2005] came out, so I asked him what he thought about the trailer. He said, ‘Oh, I haven’t seen it.’ I said, ‘Hang on a minute. I’ve got it on my laptop.’ So I got my laptop out and booted it up. I put headphones on Ray Harryhausen and played him the King Kong trailer in the middle of this café. Nobody knew who he was there. Nobody understood that moment. But I couldn’t believe I was showing King Kong to Ray Harryhausen. It felt like a really special moment. When the trailer ended, he was blown away. He was beaming. ‘It looks fantastic,’ he said. I decided if I was ever lucky enough to meet Peter Jackson that I would tell him that story. I did eventually meet Jackson and came out with the story straight away. That was my ice breaker.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.