“When I think of the word ‘documentary’ I think of being granted a front row seat to an experience that changes the way I look at the world,” American filmmaker Alan Berliner writes by email. Berliner was present at the 18th edition of It’s All True (IAT), Brazil’s largest documentary festival, which occurred this year throughout four cities. “A good documentary functions as either a window in which I look through the frame to observe and learn about the world outside myself and my own experience, or a mirror in which I find myself reflecting upon my own life and my own place in the world in relation to the subject at hand. The best documentaries somehow manage to do both.”

I wasn’t merely watching a film, but voting in a referendum on the value of memory.

One can say that the best experimental films also do this; like many strong documentary films, they challenge the viewer to raise his or her awareness of the world beyond the frame. This year’s edition of It’s All True (named after the legendary aborted Orson Welles film shot in Brazil in the early 1940s) explored the relationship between documentary and experimental film traditions explicitly through a two-day conference organized around the topic, as well as implicitly through several of the films selected.

But what does the word “experimental” mean? Can there be experimental traditions? Documentaries have standardized their forms to the point where the majority of readers likely have an idea of how any given doc will unfold before they watch it. Yet so have experimental films, whose subcategories are as easily classifiable as those in the documentary field. The historical documentary that recounts the past through straightforward presentations of archive footage finds its counterpart in compilation films that manipulate archive footage in many directions; the performance documentary that focuses on musicians or artists putting on a show is an oft-talkier version of the structural film, whose performer is the filmmaker, and whose instrument is the film material itself. Experimental films are often deathly predictable—as speakers at the conference pointed out, they’ve earned their categorization by looking and sounding like films that have been called experimental in the past.

What makes a film truly experimental is a filmmaker’s test to see what will happen, without knowing the result in advance, if he or she creates a form to fit a subject. The most exciting documentaries are often experimental. Berliner’s latest film and an IAT special event, First Cousin Once Removed, is a case in point. Ostensibly the film is a portrait of Berliner’s aging cousin, the poet Edwin Honig, as he slides into Alzheimer’s. Berliner discovered that Honig’s levels of lucidity would vary greatly, and created a film whose form explores them. Tightly edited sequences will often rapidly show several successive close-ups of Honig remembering and forgetting details of the same story, sometimes struggling with his memory loss and sometimes at peace with it. The effect is that of a man in dialogue with himself. Ultimately, Berliner’s film suggests, anyone can identify with Honig’s human condition.

The film’s assemblage, less linear than fractal, is meant to give an impression of its subject’s non-narrative mind. “I’m simply a storyteller who tries to make the way I tell a story as interesting as the story I’m telling,” Berliner writes by email. “I think my work certainly borrows from certain documentary methods and tropes, but my overall process is so eclectic and filled with so many other kinds of puzzle pieces that I’m never quite comfortable using the ‘d’ word.”

For some artists that word has become tainted with staid formal associations, and in recent years the term “nonfiction filmmaking” has emerged as an alternative to it. While one could complain that all films, at some level, are nonfiction filmmaking, in a way this is the point—part of the term’s potential value lies in the way in which it allows for many different subjects and approaches to broaden a previously much narrower category, similarly to how “nonfiction writing” can encompass diverse kinds of texts that range from car manuals to history textbooks to confessional memoirs. A group of artists and researchers involved with Harvard University’s Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL) have recently become prominent nonfiction filmmakers, with their goal being less to tell stories than to create environmental immersions. Their films wed form and content by plunging viewers into sensorially overwhelming experiences that call attention to the act of filming itself. In the group’s film Sweetgrass (2009), the viewer moves around Montana mountains with sheepherders, sometimes coming face to face with the animals themselves; in last year’s Leviathan (2012), the viewer comes to experience the feeling of life at sea through sounds and images captured with swinging cameras affixed to fishing boats. The SEL film People’s Park, an IAT selection, also weds approach to environment. J.P. Sniadecki and Libbie D. Cohn’s film explores a crowded public park in Chengdu, the capital of China’s Sichuan province, primarily through a single seventy-eight-minute-long tracking shot that begins and ends with a variety of people dancing together. A multitude of wanderers enjoying the day are captured in between.

“The architecture, the social space, and sensorial experience of movement through the park seemed to call for a sustained, continuous itinerary that would foreground its indelible details, its surfaces, textures and sensual dimensions,” Sniadecki and Cohn write by email. “Rather than use editing and impose an ex post facto hierarchy of meaning, we wanted a more democratic treatment of all the park’s aspects and lifeforms. We wanted to cede some of the authorial control and meaning-making of montage, and open the film up to the serendipitous, the unplanned and the accidental. This is not to say that we disavow our roles as directors, and the one-shot approach grants People’s Park a formal structure upon which we invite a wash of portraiture, performance and provocation. We also felt that, working with the performers in the park, we needed a similarly performative role or identity in order to parallel their activities.”

Yet while the technology that these particular chroniclers are using is new, and their approach can even reasonably be called experimental, the tradition of a chronicler attempting to bring as much energy and passion to his work as the world he is chronicling possesses is longstanding. It’s there in the Swiss writer Robert Walser’s short turn-of-the-20th-century pieces written full of commas, exclamation points and long-running sentences penned in an effort to swallow Berlin whole, and in the confident lines that Walt Whitman wrote as though wrapping his arms around all fellow creatures. And it’s there in the great experimental documentary film movement of the city symphony, which reached its peak in the 1920s and whose most celebrated example, Dziga Vertov’s 1929 Man with a Movie Camera, played at IAT as part of an all-35mm Vertov retrospective.

Because of this virtuosic, toolbox-deploying film that looks at a city’s daily life through a dizzying number of ways, Vertov has often been seen in the West as an avant-garde filmmaker. Yet as pointed out at IAT by Austrian film museum researcher and curator Adelheid Heftberger (whose institution provided the festival’s Vertov prints), in modern Russia he’s much better-known as a presenter of Soviet daily life, with the overtly propagandistic Three Songs About Lenin (1934) his most cherished film. While critical discussion of Vertov often emphasize the “movie camera,” they can also emphasize “man.” And indeed, attending the retrospective revealed that Vertov took extraordinary care, and even love, in capturing the faces and bodies of his human subjects, who wer often poor workers; a film like Kino-Eye (1924) transports a viewer through town and country along the backs of ditch-diggers, hospital workers, and street cleaners. The movement of city life in particular is captured with as much racing vitality as the sensations of a daily urban sprint CAN bring. (This vitality was undermined by the abominably slow speed at which I saw Kino-Eye projected during IAT—though the projection speeds of Vertov’s silent films depend on each projectionist’s judgment, the movies work best when played fast.)

Heftberger says that she sees Vertov more as a documentarian than as an avant-garde artist, but that his willingness to play with form is part of what makes his documentaries great. “Vertov strove for the authentic image,” she says. “And what I miss in documentaries right now is the willingness to formally play with what’s at your disposal while still striving for it. Vertov can teach us how every image in a film has meaning, even if that meaning is not immediately clear. He can do many different things with images and even sometimes reuse them, giving them new meanings within each new, specific context.”

And this is perhaps what nonfiction cinema can ultimately do. It can educate through exposure not just to factual information, but also to different approaches and ways of thinking. It can teach viewers not just that each subject can be approached differently, but that each subject should be.

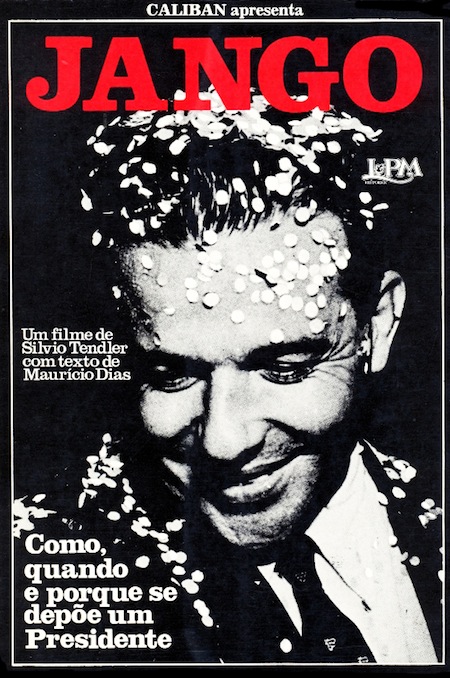

For instance, there is the rigorously expository approach taken by Brazilian filmmaker Sílvio Tendler, whose 1984 film Jango proved the highlight event of the retrospective “Jango and the Road to 1964.” The film’s title refers to the nickname of Brazilian President João Goulart (1919-1976), a leftist leader who proposed major economic, educational, work and land reforms in the interests of improving the fate of the nation’s poor. He was then deposed on April 1, 1964, by a military coup that led to 20 years of military dictatorship in Brazil. As in several other South American countries, fascism deposed socialism in the name of defeating communism, and then later become totalitarianism. (And, as in several other South American countries, the United States government aided the military.) Jango watched his country’s history unfolding during his subsequent years in Uraguay and in Argentina, where he became the lone Brazilian President to die in exile.

Tendler’s method of showing what happened, in this film as well as in others (including his The JK Years [1980], which discusses the political trajectory of the earlier Brazilian President Juscelino Kubitschek), will be familiar to many viewers from other traditionally told documentaries: A chronological movement through archive footage, connected by voiceover, with experts explaining what happened and when during interspersed present-day interviews. In the process, the films—among the first to discuss Brazilian politics as they worked before and during the dictatorship—uncover much information that had previously been buried. Their textbook approach was appropriate because of the need they served, which was to fill in a space containing a number of years that the military dictatorship had erased.

Tendler writes by email today that at the time of Jango’s release, “On account of censorship, and above all because of the school system and of people’s fear to speak, Brazil lived unaware of its own history.” For the half-million viewers who saw Jango upon its initial theatrical release, the film helped raise awareness. Tendler, who refers to The JK Years as the first film to discuss the dictatorship (which to my knowledge is true), continues that, because of his films, “Doors were opened to knowledge that had been hidden about a country.”

As the coup’s fiftieth anniversary approaches today, Tendler’s films still hold this function. Unlike in some other countries formerly ruled by military dictatorships, where the need to remember dictatorship years can sometimes register like a national obsession, one hears relatively little within Brazil about this time, as though it were a trauma to be suppressed. Yet the sold-out screening I attended of Jango contained an audience whose members (many of them under 30) applauded loudly throughout. The world beyond cinema became clearer than usual for me that day. I wasn’t merely watching a film, but voting in a referendum on the value of memory.