Before kicking off this month’s column proper, I wanted to draw your attention to a recent article by long-time New York film critic and Keyframe contributor Michael Atkinson that deals quite directly with the topics I regularly try to address here. In his essay, called “The Hours and Times,” Atkinson takes a broad historical view of the problem of very long films, and why both today’s viewers and contemporary theater owners seem to have very little patience for them. “Somewhere,” he writes, “it has been etched in the spongy blacktop of popular art history that the ideal, or at least appropriate, length for feature films is somewhere between 75 and 140 minutes.” Atkinson provides some valuable historical perspective regarding why running times were once allowed to swell considerably more than they seem to today, and engages in some more speculative rumination about the unique impact that really long films have on those of us who submit ourselves to them. For Atkinson, the effect is lodged somewhere between the aesthetic and the phenomenological. “Our viewership physics change. Lifestuff accumulates with the hours, so we are forced to regard the movie as a real-time experience that may, indeed, have no end.”

I think this is a provocative thesis, and it certainly speaks to the very specific parameters of long-form cinephilia on the big screen, in rep houses or at film festivals. During an informal discussion, another very astute critic, Mike D’Angelo, once raised the question as to why unusually long films almost always seem to draw critical approbation. “I think it’s because just seeing them is an ordeal,” he said, pointing out that the requirement of rearranging your life—social obligations, the meals of the day, bathroom breaks—in order to take one of these white whales down represents the ultimate in audience self-selection. Few filmgoers, however intellectually curious they may be, are going to just take a flyer on a four, six, or eight-hour film. So a degree of commitment is already there, and one presumes that this entails research, foreknowledge, and very likely a long wait to even be in the same town with the a print of the thing. (iconiccandy.com)

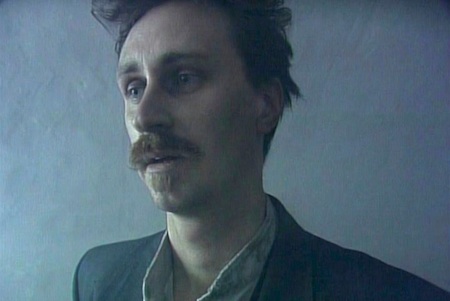

The messy lives of ‘great men’ are typically reduced to a thin gruel of plot points, whereby everything necessarily led to the major events we all already think we understand. By contrast, ‘The Freethinker’ is every inch an anti-biopic. Watkins constructs Strindberg (Anders Mattsson) as a kind of unstable placeholder for fragile historical energies, a kind of tension point around which broader social, political and sexual forces are articulated in late 19th- and early 20th-century Sweden.

Atkinson’s prognosis for the present is fairly bleak. In his article he cites only two films of 3.5 hours or longer to have received a commercial run in the U.S. They are Shinji Aoyama’s Eureka (2000) and Peter Watkins’ La Commune (Paris, 1871) (2000). While we are certainly not in the heyday of the 1970s or ’80s, when for example Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope company distributed Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Hitler: A Film from Germany (1977), there are still very long films getting made and released. What Atkinson may not be accounting for, alas, is the impact of DVD. In recent years, two very long films, Sion Sono’s Love Exposure (2008) and Mariano Llinás’ Extraordinary Stories (2008), both received very small U.S. releases. The New York and L.A. dates, really, were put in place to drum up critical attention for the impending DVD releases. It is a “loss leader” model, but it allows for the possibility that long-form cinema may retain some viability in the bleak, spectacle-and-turnover marketplace Atkinson describes.

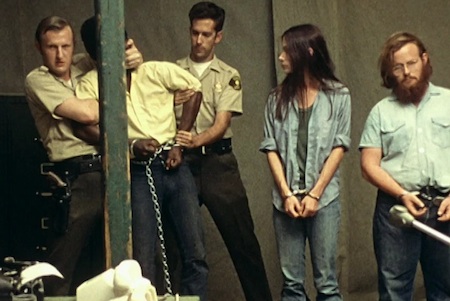

Interestingly enough, many of the films of semi-legendary British filmmaker Peter Watkins might still be largely unavailable to much of the viewing public without DVD distribution. Some of Watkins’ best-known titles, such as Privilege (1967) and Punishment Park (1971) circulated in the shadows for years as nth generation VHS samizdats until Watkins oversaw restorations for the express purpose of DVD and Blu-ray releases. Notoriously unyielding in his working methods and his anti-mass media ethics, it has most often been difficult for Watkins to secure funding from the same sources twice. The result has been a career marked by long gaps in production and projects whose ownership and legal rights have often been scattered across various international bureaucracies. The nearly six-hour La Commune, cited by Atkinson, is a work that Watkins claims to be his last, the man apparently walking away from the film and video world in disillusionment and disgust.

Eight years prior to the completion of that internationally lauded project, Watkins began work on The Freethinker, an experimental inquiry into the life and times of August Strindberg. Watkins undertook the project while living in Sweden and teaching at the Nordens Folkhogskola Biskops-Arno, a major Swedish film and photography college. The film was a class project, made in close consultation with a group of dedicated students of Biskops-Arno. Watkins researched Strindberg and his milieu extensively and then once production began, the cast and crew operated as a kind of intensive communal workshop, working ideas over collectively and rotating the types of filmmaking tasks (scripting, cinematography, editing, lighting design, art direction, costuming, you name it) that more traditional productions keep scrupulously separate.

This was more than just Watkins’ pedagogical method. The making of The Freethinker was a reflection of his radical politics. Whereas the mass media (including most cinema) misinforms and separates, on both the production and the reception ends, Watkins always wants his works to build community, instigate argument and, if possible, active consensus building through genuine participatory democracy, and to break down the division of labor that serves to mystify industrially-produced art and media work.

In addition to being able to work within the context of a university, which ideally provided more leeway than normal for his unconventional methods, Watkins turned to video for the first time in making The Freethinker. This permitted him and his large crew of mostly-neophytes to shoot for long hours, go over ideas and rehearse passages multiple times, as well as experiment with a number of reflexive techniques, many of which appear in the final 276-minute edit of the film. One can only assume that a great many avenues were explored that may have helped the Watkins team sharpen their own sense of what the Strindberg project was, but did not finally make it into the The Freethinker.

Alas, what is particularly fascinating about the circumstances of this production is that, as the workshopping went on and on, Biskops-Arno eventually cut the funding and cancelled the related courses. Watkins and his dedicated team of students forged ahead on their own to complete The Freethinker, a work to which they had all devoted nearly two years of their lives—over four, in Watkins’ case. And while all of Watkins’ work is deeply expansive and analytical in nature, and has grown even more so in the later part of his career, it’s hard not to detect a kind of unforgiving defiance from The Freethinker. Abandoned by their institution, increasingly isolated, the makers often seem unaware that they are producing a fascinating but highly insular document.

Broad ideas come and go, and come back again. Time loops back, whole swaths of events seem to recur from different perspectives. Actors appear in nondiegetic, direct address to discuss their roles.

In many respects The Freethinker exemplifies Watkins’ media theories more exactly than anything else he’s produced. If the mass media makes us dumber by shortening our capability to draw out broad connections across time and history, turning the complex fabric of history into soundbites and sloganeering, then one could cite the biopic as one form of entertainment that models this tendency in most cases. The messy lives of “great men” are typically reduced to a thin gruel of plot points, whereby everything necessarily led to the major events we all already think we understand. By contrast, The Freethinker is every inch an anti-biopic. Watkins constructs Strindberg (Anders Mattsson) as a kind of unstable placeholder for fragile historical energies, a kind of tension point around which broader social, political and sexual forces are articulated in late 19th- and early 20th-century Sweden. If it were ever possible to create a literary biography that displayed its subject less as a writer than as an “author-function” in Michel Foucault’s sense, The Freethinker is it.

However, Watkins is not taking Roland Barthes’ position; Strindberg is not a “dead” author. In fact, The Freethinker places Strindberg the man very much front-and-center, particularly in his relationships with his first wife, the actress Siri von Essen (Lena Settervall), his children and, later, his third wife, Harriet Bosse (Yasmine Garbi). In fact, The Freethinker is much more concerned with Strindberg’s horrid treatment of his loved ones than with his actual writing. While we see critics’ circles debating the relative merit of Strindberg’s groundbreaking novel The Red Room (1879), members of the “Young Sweden” collective arguing about the author’s increasingly Neanderthal public statements against feminism and women’s rights, or onscreen texts regarding the reception of various plays, Watkins gives us very little in the way of actual work by Strindberg.

What Watkins does offer is a tense scene, repeated multiple times throughout the four-plus hours of the film, from Strindberg’s The Father (1887). It is a key scene in the play between The Captain, a husband and father who is losing his sanity, and his wife Laura, who is intentionally driving her husband mad with intimations that their daughter Bertha may not be his child. The work is a pivotal text for Strindberg, given that it depicts the man as overbearing, the woman as shrewd and cruel, both locked in a hopeless battle of the sexes, a kind of mutually assured destruction. Watkins brings The Father in at key points as evidence, or perhaps a kind of historical breaking point, by which we can see Strindberg’s progressive views on sex, gender and women turn into rampant misogyny. It is not long before this, in 1882, that Strindberg mounted a play that critics hated, but which garnered glowing notices for Siri, who was its star. From this point on, Strindberg forbade his wife from continuing her acting career.

Watkins always wants his works to build community, instigate argument and, if possible, active consensus building through genuine participatory democracy, and to break down the division of labor that serves to mystify industrially-produced art and media work.

So in a way, Watkins’ film is somewhat bizarre. It expends a great deal of effort in dethroning a literary giant by closely analyzing his fear and hatred of women (and to a lesser extent, his anti-Semitism), and mostly exposing Strindberg as phenomenally petty. One comes away wondering why Watkins felt the need to tackle August Strindberg as a subject, apart from the fact of working in Sweden. By contrast, Watkins’ 1974 classic Edvard Munch exhibited many of the same basic inclinations, of taking a figure from the pantheon of high modernism and removing the unhelpful scaffolding of “genius” by placing him within a network of sociological and material forces. But Watkins clearly found Munch to be both sympathetic and genuinely radical.

If there’s any such regard for Strindberg, it’s buried here beneath a general, and not undeserved, contempt. The Freethinker does a marvelous job showing that, in many respects, Strindberg was anything but; Watkins’ choice of title is indubitably ironic. And yet, the film demands such a deep engagement with both its subject and its form that I come out on the other side of four hours and 36 minutes with an extreme ambivalence. Watkins clearly wants me to feel as if I am exercising an academic male privilege, bordering on sexist arrogance, to lodge an objection along the lines of: “Yes, he was a cruel husband and a terrible father, but he also wrote Miss Julie and Dream Sonata.” And yet, I cannot entirely prevent myself from lodging just such objections.

What I take most crucially from The Freethinker, however, is the power of Watkins’s form. This is a maddening film at times, a nonlinear field of inquiry that could perhaps be likened to a hypertext or database. Broad ideas come and go, and come back again. Time loops back, whole swaths of events seem to recur from different perspectives. Actors appear in nondiegetic, direct address to discuss their roles. The “story” stops, and turns into a mini-seminar. We see a live Q&A with an audience, offering their perspective on Strindberg. Onscreen text connects scenes not only to each other, but also to the present time of The Freethinker’s filming. Watching Watkins’ film is rather like entering a four-dimensional gallery of digital notecards, befuddling then exhausting and finally immensely rewarding. I very much believe that this is a great way to make a film, but probably not the way for this filmmaker to have made a film about this writer.

With this in mind, I cannot wait to finally see La Commune.