Born: April 26, 1893, Sissons, CA

Died: August 18, 1981, New York, NY

She was the first practitioner of the wisecrack for the screen.

—Gary Carey

Perhaps the most unsung creative artist in motion pictures was Anita Loos. No other writer in film history can lay claim to her sheer artistry. Her terse, clever title cards came to define screen personalities in the silent era. Loos was in tune with moviegoing audiences and knew exactly which linguistic approach would send them into howling laughter. Mastering the ability to make audiences anticipate her next comment, she would surprise and delight them with unexpected wordplay or double meanings. Her words had the power to create stars and level governments. She was the unspoken “voice” of Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, and she crafted a tone and delivery that established the essence of Hollywood dialogue.

Surrounded by performers all her life, Anita Loos grew up on the streets of New York playing with childhood friends Helen Hayes, Adele Astaire and Paulette Goddard. At the age of sixteen, she went to work for D.W. Griffith writing a script for the Mary Pickford film The New York Hat (1912). One of the first film scenarists (most then were women), she received fifteen dollars a week for her story ideas, many of them humorous. She wrote a staggering 105 scripts in the next three years, including several of Biograph’s early commercial successes.

After seeing simple title cards used in early films for exposition, Loos urged Griffith to let her explore them as dialogue cards. Griffith, although partial to her humorous writing, was unimpressed with the prospect. His position was that “people don’t go to the movies to read,” but Loos persisted. After she presented some examples, he reluctantly conceded, and Loos was soon writing witty phrases that are credited with helping making Douglas Fairbanks a star in His Picture in the Papers (1916). It was the introduction of satire to silent film. Griffith was converted, Fairbanks was transformed into a star and title cards were a permanent fixture.

Loos’s silent wisecracks seemed to mock the Victorian values of most silent productions and drew humor from the moviegoing experience itself; in a Fairbanks adventure that featured a villain with an unpronounceable name, she tickled audiences with a title card that said, “Those of you who read titles aloud, don’t attempt to pronounce his name. Just think it.” Theater patrons sat up and eagerly awaited her next screen gem. Loos was the first writer to make sexual innuendo an integral part of highbrow film comedies. She was also one of the first known to the public by name, and she playfully winked at her followers by giving herself equal billing with the authors of classic literary works: a title card for Macbeth read “Written by William Shakespeare and Anita Loos.” Today’s flippant one-liners spoken by action stars after climactic moments are pure Loos. Her spirit is present in the smug “Hasta la vista, baby” of Arnold Schwarzenegger in Terminator 2 (1991) or the cynical “Go ahead, make my day” of Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry in Sudden Impact (1983). Loos turned wisecracking into movie language distinct from stage wit.

Until 1920, writers of title cards attempted to mimic the sharp-witted humor that Loos initiated, and many failed dismally to reproduce her talent for deft understatement. More important, other silent films were becoming tiresome and repetitive; it seemed Loos had added a personality and bite to them that moved the art form into a new era of maturity. Her subtitles strongly supported characterization and suggested a speaker’s “tempo.” Good subtitles, she demonstrated, could clarify the action in a scene and help propel the plot forward.

Loos developed a prestigious reputation for her writing on more than two hundred films, including Griffith‘s Intolerance, several Shakespeare adaptations and a popular treatment of Clare Booth Luce’s play The Women (1939). Sought after by other studios, including Reliance, Lubin and Metro, she would remain on of the most prolific and well-paid writers in Hollywood, finally accumulating more than 250 screen credits in her career. Her success drew attention to the screenwriter as a creative artist equal to the director and allowed audiences to see that movies were written and not merely ad-libbed, and her biting wit paved the way for Dorothy Parker and other women writers who came to assume similar prominence in Hollywood.

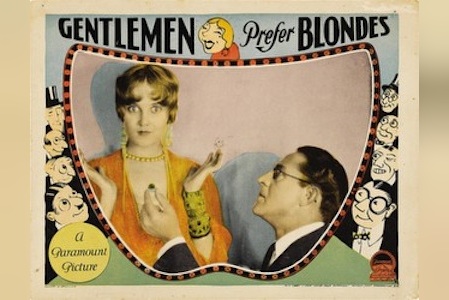

Screenwriting led her to other forms of writing—a 1925 comic novel, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, became a bestseller, which Loos subsequently adapted for the screen in 1928.

In 1929, Loos joined MGM at the request of Irving Thalberg. Female screenwriters then outnumbered males by nearly ten to one, and she was instrumental in guiding some of the talented young screenwriters of the era, especially Preston Sturges, while pounding out scripts for sound films. Actress Jean Harlow became a recipient of Loos’s cynical banter in Red-Headed Woman (1932) and opposite Clark Gable in Riff-Raff (1935) and Saratoga (1937). The breezy lines of Loos’s script slipped off the sexy lips of Harlow with ease and became her trademark delivery.

Despite penning the exploits of characters in all kinds of exotic settings, Loos rarely traveled outside the country, dividing her entire life between New York and Hollywood. A diminutive woman of four feet, eleven inches, she died at the age of eighty-eight. In her old age, she assisted historians in restoring many of her films in the 1970s and was careful to remind them of the contributions made by women screenwriters.

Few have ever matched the style of the teenage scenarist who literally set the tone of movie dialogue. Among other gifted screenwriters of the day, including such pioneering females as June Mathis, Frances Marion and Jeanie Macpherson, she was the most successful at creating a voice and personality for the stars of the silent screen. The clever banter that Hollywood scripts favor is the direct result of her prolific lines. A telltale anecdote of her influence comes from a Photoplay interview in 1917. Reporter Julian Johnson was interviewing D.W. Griffith, and when the name of Anita Loos came up, the stately director placed a finger over his mouth, paused to collect his thoughts for a moment, smiled and said simply,” The most brilliant young woman in the world.”

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.