The question on many minds as The Grandmaster opens the Berlinale today: Will Wong Kar-wai bounce back after My Blueberry Nights (2007)? That rather vacuous first feature in English had some of us wondering whether the lushly saturated cinematography, floating camerawork, spectacular set design, and impossibly gorgeous casts of his previous work had seduced us into believing that there’d been less there there all along.

But heaven knows, we’ve been rooting for a comeback. Since, at the latest, Quentin Tarantino championed Chungking Express (1994) and Sofia Coppola began quoting a few of his trademark moves, Wong has seemed destined for the pantheon. By 2010, when it came time to assess the first decade in the new millennium, we knew that In the Mood for Love (2000) was a stone-cold classic. Mood and David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2003) battled it out for top positions in countless best-of-the-Naughts lists, and in the 2012 Sight & Sound critics poll—the best films of all time!—Mood landed in the #24 spot, four notches above Mulholland.

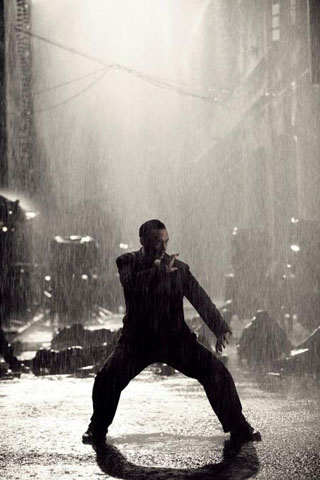

Since My Blueberry Nights, Wong has been working on his biopic of Ip Man, the martial arts master probably most famous for having taught Bruce Lee. But that is not all. He’s also been making a handful of shorts and, most tellingly, commercials, polishing up cosmetics, perfume, whiskey, and flatscreen TVs with a sheen that isn’t quite as unique as it once was now that so many others have learned how to imitate it. When the credits rolled at today’s afternoon screening of The Grandmaster, many of us rose and began to file out of the theater—until, wait, extra scenes: Ip Man (Tony Leung), fighting again—cut, cut, cut! Every which angle, cut again!—before turning to face us and expounding a bit more on how no one martial arts style is necessarily superior to any other. Frankly, this add-on is little more than a limp trailer for the film we’d just seen. And then, still talking directly at us, I kid you not: “What’s your style?” Had Leung then held up a glass of whiskey, all glowing amber, I would not have been surprised.

Since The Grandmaster opened in China last month, reviews have ranged from the generally positive to the near-ecstatic. I’m not familiar with critics Clarence Tsui (Hollywood Reporter) and Edmund Lee (Screen), but I do know and, to a considerable extent, trust Maggie Lee (Variety) and James Marsh (Twitch). And, all due respect and all, I simply cannot tell where they’re coming from. Maggie Lee: “Boasting one of the most propulsive yet ethereal realizations of authentic martial arts onscreen, as well as a merging of physicality and philosophy not attained in Chinese cinema since King Hu’s masterpieces, the hotly anticipated pic is sure to win new converts from the genre camp.” James Marsh: “In The Grandmaster, Wong Kar-wai has crafted the best-looking martial arts film since Zhang Yimou’s Hero, and the most successful marriage of kung fu and classic romance since Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and is more than deserving of that film’s measure of international success.”

I don’t see that happening. Granted: There are shots in The Grandmaster of undeniable beauty; cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd has pulled back the saturation dial from eleven, where Christopher Doyle’d left it. But there are few sequences that actually cohere. Yuen Woo-ping’s choreography is probably damn impressive (and to hear Leung and Zhang Ziyi tell it, they worked themselves to the bone to get it down), but Wong’s action sequences suffer from the same sloppiness of construction that Jim Emerson has analyzed in the films of Christopher Nolan. Further, the film as a whole has been pieced together from stylistically incongruous modules: the fights and the long stare-downs that proceed them do echo the pageantry of mid-2000s Zhang Yimou, but throughout the film, they’re disarmingly set next to poorly integrated spurts of exposition: documentary footage, title cards, voice-over narration, all of which kick the story a bit further down the road but nearly none of which shed any light on these paper-thin characters. I do agree with Maggie Lee’s argument that Zhang Ziyi comes off far more convincingly than Tony Leung in that her character, Gong Er, rides an arc—whereas nothing, not even war and a Japanese invasion, the loss of his family, or outright destitution even budges the straight-arrow trajectory of Leung’s Ip Man.

While I’m sure it’s not true, I can’t help but wonder whether Wong, who’s been dreaming up this project for 16 years, has spent the past five years making clips alongside those shorts and ads that he trusted would, once strung together, produce a sweeping epic. Not to these eyes. That said, I still hold on to the hope that Wong gets it together again before he’s swept off that path to the pantheon.

Updates: The Weinstein Company has acquired U.S. rights, reports Rachel Abrams for Variety.

Blogging for the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Brian Brooks has notes on today’s press conference. So, too, does Peter Knegt at Indiewire, where Eric Kohn finds The Grandmaster to be “satisfyingly in tune with the contemplative nature of the director’s other work, only breaking his trance-like approach to drama for the occasional showcasing of martial arts techniques.”

Writing for Film.com, Stephanie Zacharek finds “something oddly sterile about The Grandmaster; it’s too meticulous to be genuinely fervid. Even Zhang Ziyi’s unassailable gorgeousness—her skin is like a porcelain night-light—in the end seems curiously flat, a movie-magazine rendering of feminine allure. Those of us who love Wong, and who patiently wait out the interminable years between his movies, demand a specific kind of greatness from him: We want his movies to be overwhelming but delicate; supple but sturdy; hypnotic but assured. The Grandmaster is trying to be all those things at once, and it’s perhaps the ‘trying’ that’s tripping it up. But one thing is constant: Leung holds that camera. His face is almost a movie unto itself. The filmmaking around him is just an excuse.”

“Considering Wong’s work at its best is an exercise in sustained mood and tone, his inability to maintain it here is among the film’s chief disappointments,” finds Jessica Kiang at the Playlist.

Thomas Groh, writing at Perlentaucher, is also disappointed. Also in German: Andreas Borcholte at Spiegel Online.

Updates, 2/8: At HitFix, Guy Lodge finds that “for every creative decision here that feels exquisitely, exhaustively considered, there’s another that feels entirely careless or, worse still, compromised.” Consider Leung’s “What’s your style?” line, for example: “He may be referring to the dizzying array of martial arts schools and disciplines covered in this valentine to the physical art form, but he could as easily be Wong himself, shrugging to any audience members confused by his own straying aesthetic. Either way, it’s an arch, even camp, flourish that suggests he may not be taking the enterprise entirely seriously—or at least wasn’t at one particular juncture in the editing process. Elsewhere in this protracted tale of love and war on the kung-fu power ladder, proceedings could hardly be more po-faced—this uneasy tonal range another symptom of a film perhaps left stewing too long.”

“The Grandmaster possesses nothing like the bounding, light-on-its-feet energy of Lee’s [Crouching Tiger],” writes the Guardian‘s Andrew Pulver. “Wong’s film is much more a study of ideas and textures, designed to ravish the senses.”

“Traces of Wong’s favorite themes are recognizable throughout,” writes Giovanni Marchini, dispatching to the Film Society of Lincoln Center, “for example in the impossible love between Ip Man and Gong Er, but these too are not given enough room to breathe and truly develop. In aesthetic terms, however, Wong does not disappoint.”

At Thompson on Hollywood, Tom Christie is upbeat on the film’s commercial prospects.

For those who read German, Film Zeit is collecting more reviews. Lukas Foerster argues that the digital projection here at the Berlinale was nothing less than a catastrophe.

Updates, 2/10: The Telegraph‘s Tim Robey finds that Wong’s “most mannerist tendencies have bloomed unhelpfully in the last decade, and long stretches recall the distractable, wandering inertia that made 2046 such hard work. It may be that indulgence has got the better of him—surrendering to the movie involves being willing to give him quite a long leash. In the absence of genuine profundity, but with dazzling craft on frequent display, his most ardent devotees may summon enough loyalty to defend this one as a noble failure.”

Adam Cook in the Notebook: “Beginning awkwardly with an alternately beautiful and illegible action set-piece, The Grandmaster finds its footing when it retreats to the territory of Wong’s wheelhouse: unrequited love, careful, minute gestures, montage flourishes that compress time but expand emotions.”

Updates, 2/13: “Look no further than Wilson Yip’s recent series of Ip Man movies to see what a difference an auteurist sensibility can make with the exact same material,” writes Stephen Garrett for Time Out New York. “Those iterations, starring Donnie Yen and choreographed by Sammo Hung, were straight-up entertainments, with teeth-rattling action, maudlin sentimentality and heartwarming uplift. But Wong, who uses Ip Man’s story as a foundation for more sociopolitical and even metaphysical notions of identity, astonishingly infuses his trademark aching melancholy into all the fight scenes…. As one character explains, there are three steps to the path of a Grandmaster: being, knowing, and doing. As a director, Wong has clearly attained the title.”

“Essentially a biopic wrapped in a kung-fu art film, The Grandmaster‘s ambition but feeling of incompletion brings to mind Sam Peckinpah’s analogous probing of national history, mythology, and masculinity,” suggests Joseph Pomp at the House Next Door.

For Christopher Shea, writing for the Phoenix, “full enjoyment of the movie probably rests largely on your belief in the infallibility of Wong Kar Wai’s genius. Seen through this lens, the movie’s inscrutability is a sign of mastery; its nearly incomprehensible early scenes—during which we learn the details of 1930s Sino-Japanese politics and the history of Kung Fu—aren’t sloppy, but deliberately, unsettlingly obscure. If you trust that your ignorance of Kung Fu wisdom and Wong’s craft lie behind these little confusions, you’ll love the movie; otherwise you might find it satisfyingly epic, but opaque.”

More, in Spanish, from Diego Lerer.

Update, 2/18: For the New York Times, Dennis Lim talks with Wong about The Grandmaster and about heading up this year’s International Jury.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.