Born: May 12, 1907, Hartford, CT

Died: June 29, 2003, Fenwick, CT

You never pull up a chair for Kate. You tell her, ‘Kate, pull me up a chair, willya, and while you’re at it get one for yourself.’

—Humphrey Bogart

Katharine Hepburn broke the glass ceiling in Hollywood long before anyone had even heard of the glass ceiling; her determination and intelligence kept her on course through a glorious career, devoid of compromise. Her screen performances enabled men and women to be seen on an equal footing, and she deliberately shunned roles that required her to play women in conventional situations. Perennially listed among the most admired women in the world, Hepburn was the very essence of the cosmopolitan woman, a scrapper who took charge of her own career for more than six decades and led an exceptionally liberated lifestyle that both offended and inspired women in the modern age.

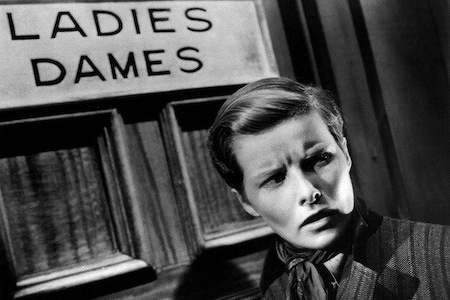

Her own influences were highlighted by an upbringing in a wealthy New England home, where her mother was an early crusader for women’s rights. The young, tomboyish Kathy preferred to wear her brother’s clothes and was often sent home from school to change into a dress. By the time she appeared in her first film, strong female roles had come to Hollywood. Inspired by several of the outspoken women in her own family, Hepburn created a number of feminist characterizations in such early films as A Bill of Divorcement (1932), Little Women (1933) and Stage Door (1937). Perhaps no film foreshadows Hepburn’s career more than Christopher Strong (1933). Directed by the pioneering female director Dorothy Azner, the film featured Hepburn as a daredevil aviatrix who falls in love with a married man and begins a love affair that threatens to destroy his family.

Hepburn’s early movie roles, under the guidance of such forward-thinking directors as George Cukor and George Stevens, were groundbreaking characters that challenged the accepted gender norms of society. Cukor’s Morning Glory (1933) earned Hepburn her first Best Actress Oscar, and Alice Adams (1934) secured another nomination. But by Sylvia Scarlett (1935), her smart, spirited woman-in-trousers performances upset conservative theater owners, who canceled many of her films rather than answer to their Middle American constituencies. Despite work in comedy classics such as Bringing Up Baby (1938), Hepburn had turned into a public relations nightmare for studios.

She suffered through five straight box office failures, leading many theater exhibitors to assume her favor with moviegoers was permanently gone. Gossip columnists smelled the scent of a dying actress and began digging around her personal life, reporting on her footloose and fleeting romantic relationships with famous directors, producers, publicists and leading men. Her brief affairs with John Ford and Howard Hughes kept her in the midst of scandalous rumors. Reported to have been dismissed as a candidate for Scarlett O’Hara in the upcoming Gone with the Wind (1939), she refused to audition for the role and left Hollywood for New York.

Starring in a successful Broadway play, she used her salary from the show to purchase the screen rights and returned to the Hollywood ranks triumphantly in The Philadelphia Story (1940). The film proved to be a rewarding comeback, bringing her exceptional praise, record-breaking ticket sales, a third Best Actress nomination and eventually the Oscar. The stage became a lifelong passion; throughout her long career, Hepburn would return to Broadway frequently, usually in roles that reinforced her image as an individualist. In the 1970 smash hit Coco, she played the eccentric Parisian fashion designer Coco Chanel to rave reviews.

Despite her growing acceptance among audiences, her long adulterous relationship with actor Spencer Tracy dominated the headlines and polarized her admirers. Despite the fact that Tracy was Catholic and married, he pursued Hepburn until an eventual divorce exposed the depth of their affections to the public. But by that time, most moviegoers already felt privy to their mutual attraction when watching the two performers work together in Woman of the Year (1942), Adam’s Rib (1949) and Pat and Mike (1952). The pair seemed a perfect match; Tracy’s masculine smugness often found a worthy adversary in Hepburn’s feline strength. Their on-screen battles spanned ten films, and their off-screen romance lasted twenty-seven years, until Tracy’s death in 1967.

Though unorthodox characters turned out to be one of Hepburn’s trademarks, she stumbled into a surprisingly offbeat role in John Huston’s The African Queen (1951) that aided her transition from youthful ingénue to strong matriarch. Hepburn took on the role of Rose Sayer, a spinster who tells a battered Humphrey Bogart after a trip down whitewater rapids, “I never dreamed that any mere physical experience could be so stimulating!” While the romantic overtones of African Queen, and subsequently Summertime (1955) and The Rainmaker (1956), softened Hepburn’s image and gave her several chances at Academy Awards during the fifties, her maturing features and air of experience left her well suited to tackle the serious subjects presented by the unsettling civil strife of America in the 1960s. She accepted challenging roles in Long Day’s Journey into Night (1962), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) and The Lion in Winter (1968), and her powerful monologues on such issues as alcoholism, homosexuality and bigotry established her as the personification of the nation’s social conscience.

At the height of feminism in the 1970s, she was finally seen as someone years ahead of her time, a woman whose career goals had superseded a need for a marriage and children. The qualities that had been labeled as too masculine for the attractive Hepburn—her stubborn determination, her imperious and competitive spirit, her political activism, her industriousness—were now the very characteristics espoused by outspoken women’s advocates who saw the actress as the embodiment of their movement. This formidable persona made her the perfect choice to play a foil to a chauvinistic John Wayne in Rooster Cogburn (1975).

She settled quickly and comfortably into more mature roles. After a bout with illness, she returned in On Golden Pond (1981), which boosted her Oscar nomination count to an unprecedented twelve and her number of wins to an equally unprecedented four, three awarded after she was into her sixties. A near-fatal car accident in 1984 slowed her again, but she rebounded to make a brief, bittersweet appearance in the romantic Love Affair (1994) and published several memoirs, including a recollection of The African Queen.

Hepburn’s contributions to the cinema were unique. Her portrayals of fiercely independent women with strong feminist dispositions paved the way for actresses like Barbara Stanwyck, Audrey Hepburn, Faye Dunaway and Jane Fonda. As a performer who actively forged her own image and exercised a producer’s control over her own career, Hepburn’s commanding presence in the film industry can only be compared to that of Mary Pickford. And though Greta Garbo and Anita Loos deserve slightly higher praise—and ranking—for their substantial influences in other areas, Hepburn’s efforts to advance the roles of women in film have since been unequaled.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.