Born: July 9, 1882, Stillwater, MN

Died: January 13, 1936, New York, NY

Samuel Rothafel was the first great showman and supreme impresario of motion picture exhibition.

—Emily Gwathmey

Samuel Lionel Rothapfel began his career in motion pictures by projecting movies to drunk miners in the back room of a Pennsylvania saloon in 1905. A one-man operator, he painted his own advertising posters, rented chairs from an undertaker, exchanged his own films and ran the projector for six shows a night. After raising enough money to travel to New York, Rothapfel struck out on his own in grand style. When he arrived, Rothapfel approached the owners of a number of New York establishments, including the Paramount, Strand, Knickerbocker, Rialto, Rivoli and Capitol theaters. He offered them a partnership proposition: he would manage them all and introduce motion pictures to their theatrical offerings.

He decided to shorten his name to Rothafel, which was displayed over his many theaters. Soon he would be known simply as “Roxy,” and his venues would begin showing films to aristocratic audiences that shied away from the bawdy entertainment of vaudeville houses. Rothafel saw an opportunity to present a luxurious environment for displaying movies to a better class of customer. His theaters would become superior to all others, and Rothafel would refer to them as “pleasure palaces.”

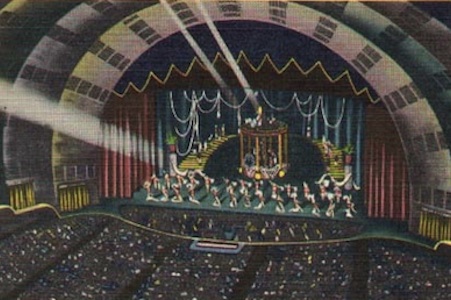

His flagship was the exemplary Roxy Theater in New York City. When it opened in 1927, it was advertised as the largest theater built since the fall of Rome. It had private apartments, a hospital staffed with nurses, a radio broadcasting booth, a kitchen and a waiting room that could comfortably hold more than two thousand people. Boasting one of the first wide-screen theaters, the Roxy had a canvas forty-two feet tall. The specially commissioned Kimball organ had three consoles facing all areas of the theater, and had six box offices and ticket sales of $100,000 a week.

The palatial quality of Rothafel’s theaters was extraordinary. Many of his finest picture houses were decorated with an opulent “rococo” flair, an excessively elaborate architectural style highly fashionable at the time. To make visitors comfortable, he installed thick carpets, cushioned seats, balconies and enormous restrooms. To add a regal appearance, Rothafel installed crystal chandeliers, oriental rugs, marble floors and gilt-edged paintings. To make his environment more elegant and accommodating, he hired uniformed attendants and built relaxation rooms decorated in Venetian, Elizabethan and colonial motifs.

Also contributing to the opulence were the huge organs that played accompaniment to silent films, adding comedic sound effects and heightening the dramatic mood. Rothafel imported international soloists to sing before screenings and kept a staff of master organists that included Carl Stalling, Lew White, Deszo Von D’Antalffy and Dr. C.A.J. Parmentier on the payroll. Many of the musicians would move on to Hollywood in the sound era as composers; others would join Rothafel on the radio.

In 1923, the National Broadcasting Company approached Rothafel about broadcasting a live program from the Capitol Theater in New York, which had fifty-three hundred seats and room for eighty musicians in the orchestra pit. As the host of a variety show, Roxy and His Gang, Rothafel presented his popular performers and organ music to audiences around the city. The broadcast ran weekly until 1931, and it encouraged thousands of moviegoers to come see a real radio show before their movie started.

During the 1930s, Rothafel’s genius for theater design was sought by other entrepreneurs. He was consulted by the Rockefellers, who wanted a dazzling launch for a concept venue called Radio City Music Hall. Rothafel accepted the project with characteristic enthusiasm. He sailed to Europe to study the great architecture of European playhouses. On the return trip, on the deck of an ocean liner, Roxy’s original concept for the Music Hall came to him. He envisioned the stage and surrounding coves to be designed as sunbeams shining above an ocean of theater patrons. The final decoration was a spectacular model of the modern theater, with glass, aluminum and chrome styled in art deco geometric patterns. Unlike any other theater in the world, the Radio City Music Hall featured a host of mechanical wonders—including eight elevators, pulleys and cranes underneath the stage—as well as the usual comforts that had become the trademark of the theater king.

With an unmatched devotion to the moviegoing experience, Sam Rothafel became known as the “high priest of the cathedral of motion pictures.” His legacy lives on today in the multiplex theaters, with their video arcades and espresso bars. He was truly one of film’s most interesting characters never to set foot in Hollywood.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.