This past holiday season, a leading American filmmaker released a historical procedural concerning a decisive period in the trajectory of one of our national icons, a talismanic figure in the bitter, arduous conflict that, arguably, most defines our country. Lincoln in Lincoln? Actually, I was talking about Osama bin Laden in Zero Dark Thirty. OBL in ZDT is something like a structuring absence, the figure hovering just outside the frame and providing the context.

In the spirit of further inscribing the outlines of American fear, here is a playlist of films dealing with existential threats, in the geopolitical sense of the term, to the state of our union. Sometimes the threat is implied by the film, and sometimes embodied in it. Some of the filmmakers are thoroughly terrorized, in hysterical thrall to their bogeymen; some are prescriptive, finding cause for teachable moments; some are reflexive, analyzing the roots of our sense of evil; and some are defiant, identifying with the spirit of transgression. Most are all of these things at one time or another.

1. The Cheat (1915, Cecil B. DeMille)

Yellow peril! In the most spectacular, flagrantly offensive scene of this early melodramatic sensation, an Asian ivory trader burns his brand into the bare shoulder of a white woman. But interestingly (if that’s the right word), the lady in question only becomes virtuous through her violation. She’s a Long Island socialite who initially symbolizes feminine frivolity, stuffing $10,000 from the Red Cross fund down her cleavage to supplement the clothing allowance granted her by her diligent stockbroker husband. Pulled into scandal by the would-be white slaver who had ingratiated himself into their garden-party set, the couple’s eventual happy ending is ensured by an angry mob of middle-aged white men. But dig, if you will, how the misogyny and race panic seem to be the displaced form of anxiety over work: the husband, whose drudgery leaves his wife idle and susceptible to corrupting influence, hunches over the stock ticker well past closing time, desperate not to fall behind.

2. The Stranger (1946, Orson Welles)

Welles’s Shadow of a Doubt, with the director-for-hire starring as the evildoer strolling down Main Street, USA, in the bright afternoon sun. He plays an escaped Gestapo mastermind posing as Connecticut schoolteacher, evading Nazi-hunter Edward G. Robinson and courting the daughter of a Supreme Court justice, played by All-American goody-two-shoes Loretta Young. Complicating the message of sustained vigilance against a seductive outsider, Expressionist flourishes with camera movement and light suggest film noir’s alienated America, and earn the title’s echo of a recently published masterpiece of estrangement from society. Welles’s Nazi marks an early postwar appearance from an archetypal baddie which the American cinema has still not exhausted; the setup of a foreign enemy within our midst also parallels the way the Red Scare would soon become Hollywood text (I Married a Communist) and subtext (Invasion of the Body Snatchers). It may also posit Welles (who seems to have ghostwritten some of his own dialogue, which he delivers with his usual European purr) as an auteur presciently sabotaging the studio system from within.

3. Invasion USA (1952, Alfred E. Green)

Speaking of the Red Scare—during which The Cheat’s director Cecil B. DeMille proved himself Hollywood’s leading McCarthyite—here’s this scared-straight thriller. It’s about fifty percent assemblage film, making use of extremely ample recent war and bomb-test footage to imagine a Soviet invasion, pieced together with strategic exposition delivered in plywood war-rooms and at a saloon in midtown Manhattan, whose denizens follow breaking-news updates which implicitly chastise their complacent patriotism.

4. City of the Dead (1960, John Moxey)

Fun with the return of the repressed: with the encouragement of her history professor, a co-ed (the very sympathetic Venetia Stevenson) drives out past the warnings of the withered gas station attend who gives her directions, to do some fieldwork in an off-the-map Massachusetts town that had burned witches in the 1690s. It seems mentioning at this juncture that the history professor is played by Christopher Lee, and that the town is a miracle of soundstage bonfire ambience, all machine-made mist and flickering light on faces. This effort from the heyday of British horror, with dubbed-in American accents and a (mostly) dressed-down Lee stepping out from his usual Hammer Studios environs, mines our Puritanical past not as allegory (though this was a few years after The Crucible), but for exoticism.

5. Punishment Park (1971, Peter Watkins)

Watkins’s faux-doc covers a near-future in which a tribunal of ordinary (Republican) citizens sentence hippies to a manhunt in the Mojave (both sides are played by nonpros sympathetic to the rhetoric they spout). But though the film is at least as propagandistic as any on this list, its bogeyman here is not the subversive element extracted and left out to bake in the sun. Rather, it’s a structuring absence: Nixon, still very much the president in this not-terribly-alternate universe. The dystopia is urgent—with obvious stand-ins for Baez, Seale and others—and explained by plausible interpretations of existing emergency-detention and anti-sedition legislation. The film’s mentality is immediately influenced by the Southern Strategy and Silent Majority speech, with early avatars of red and blue America talking past each other across an impossible gulf; and by Kent State, in its depiction of callously trigger-happy law-and-order pigs. It’s a wound-fresh depiction of a contemptuously divided nation, and the ending, which extrapolates Tricky Dick’s persecution complex into a chilling vision of authority’s contempt for the objective press, predicts his party’s eventual split from the reality-based community.

6. Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (1991, Craig Baldwin)

The ultimate—in multiple senses—Cold War paranoia film. In Baldwin’s true assemblage film, news footage and Z-grade monster movies—the front pages and funny pages of Red Scare-era America—is crazy-glued together by the most patently insane voiceover in the history of cinema, which explains how previous decades’ covert CIA meddling and overt military intervention were all part of a master strategy of proxy war against a profound and protean enemy: namely, alien invaders from the lost planet Quetzalcoatl. Like every great conspiracy theory, this explains a lot. And also like every great conspiracy theory, it’s strangely poignant in its impossible conviction—which has the effect of recasting many of the above films in a more sympathetic light, as the desperate rationalizations of a pathology.

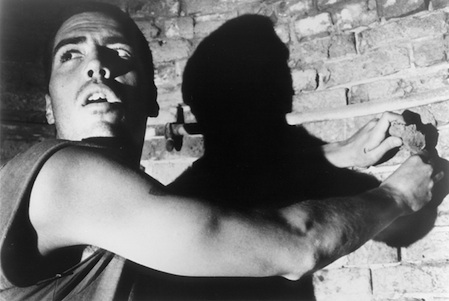

7. Poison (1991, Todd Haynes)

From the same year, another American independent which mines the depths of fifties schlock: in this triptych’s funniest segment, shot in the alarmist black-and-white of Z-grade sci-fi, a scientist acting as his own guinea pig (he’s discovered a “sex drive” formula) is overcome by his own drive for knowledge. The body-horror gags—sloughed-off skin as hot dog condiment!—wink at genre convention, while putting across an AIDS metaphor that updates the genre’s conventional encoding of timely allegory. It’s a parable from a pariah’s point of view; so too the other two segments: the sun-kissed, frankly non-normative depiction of illicit desire in a prison tale inspired by Jean Genet; and the grainy docudrama account of a young suburban boy who shoots his father and then takes literal flight, as if too pure to live. In this New Queer Cinema landmark, to be marked as different is also to be marked by grace. So appropriately, Poison, the recipient of an NEA grant, earned the ire of conservatives like Jesse Helms, who, having beaten the Soviets but lost the battle over Civil Rights, found another Other to demonize during the Culture Wars before finding a more energizing, popular external threat in the wake of 9/11.