“As a faithful rendering of a justly beloved musical, Les Misérables will more than satisfy the show’s legions of fans,” begins Variety‘s Justin Chang. “Even so, director Tom Hooper and the producers have taken a number of artistic liberties with this lavish bigscreen interpretation: The squalor and upheaval of early 19th-century France are conveyed with a vividness that would have made Victor Hugo proud, heightened by the raw, hungry intensity of the actors’ live on-camera vocals. Yet for all its expected highs, the adaptation has been managed with more gusto than grace; at the end of the day, this impassioned epic too often topples beneath the weight of its own grandiosity.”

“Victor Hugo’s monumental 1862 novel about a decades-long manhunt, social inequality, family disruption, injustice and redemption started its musical life onstage in 1980 and has been around ever since, a history of success that bodes well for this lavish, star-laden film,” writes Todd McCarthy in the Hollywood Reporter. “But director Tom Hooper has turned the theatrical extravaganza into something that is far less about the rigors of existence in early 19th century France than it is about actors emoting mightily and singing their guts out. As the enduring success of this property has shown, there are large, emotionally susceptible segments of the population ready to swallow this sort of thing, but that doesn’t mean it’s good. The first thing to know about this Les Misérables is that this creation of Claude-Michel Schonberg, Alain Boublil and Jean-Marc Natel, is, with momentary exceptions, entirely sung, more like an opera than a traditional stage musical. Although not terrible, the music soon begins to slur together to the point where you’d be willing to pay the ticket price all over again just to hear a nice, pithy dialogue exchange between Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe rather than another noble song that sounds a lot like one you just heard a few minutes earlier.”

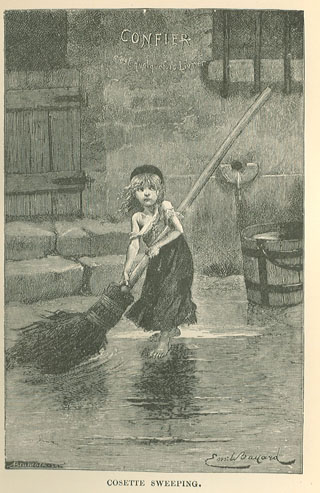

John Hazelton, writing for Screen, finds that “the singing is more natural and speech-like than it could ever be on stage. The approach preserves the feel of a musical but offers little context to ease newcomers into the story. Hooper (best known, of course, as director of The King’s Speech) chose to have the actors singing live on camera rather than lip-synching to playback and the decision gives many scenes a real emotional force…. The effect is most dramatically felt during Hathaway’s anguished delivery of ‘I Dreamed a Dream,’ one of the shows best-known songs…. Sacha Baron Cohen and Helena Bonham Carter to provide comic relief as sleazy innkeepers…. Among the individual actors, Jackman stands out for the force of his performance and the nuance of his singing. Crowe’s singing is less confident but his intensity mostly makes up for the lack of vocal range. Elsewhere in the cast, Amanda Seyfried (from Mamma Mia!) makes an appealing adult Cosette and Eddie Redmayne (from My Week With Marilyn) is strong as Cosette’s love interest Marius.”

For Time, Jesse Dorris has a quote-laced backgrounder and an interview with Hathaway. And Movieline‘s Frank DiGiacomo gathers (mostly ecstatic) reaction from a screening that took place in New York late last month.

Updates: “It’s designed to make us feel every emotion fortissimo—because pianissimo is so 1862.” Stephanie Zacharek for Film.com. “One of the tragedies of this hunk of whale blubber is that Jackman really can sing—he does the best he can with the nearly unbroken stream of sung dialogue that constitutes this damn thing.”

“Hooper’s grand canvas is impressive,” writes the Guardian‘s Catherine Shoard, “and your temples throb at the logistics of those final scenes; all those extras and horses, flags and cannons, not to mention an elephant and castle. In fact, other than a bit of a thing for distressed paintwork, it’s all but impossible to detect his thumbprints. You can’t blame him for wanting to marshall a parade, to march out of the low-budget ghetto. But the experience of sitting through all 160 minutes of Les Mis can feel less like an awards bash than an epic wake, at which the band is always playing and women forever wailing. By the end, you feel like a piñata: in pieces, the victim of prolonged assault by killer pipes.”

For the Telegraph‘s Robbie Collin, “Les Misérables is a heart-soaring, crowd-delighting hit-in-waiting: the Mamma Mia it’s all right to like.” And “the showstopper is Hathaway. When she half-sings, half-sobs ‘I Dreamed A Dream,’ hair cropped and eyes shining like Maria Falconetti, Hooper captures her performance in a single, unblinking, breath-catching close-up. This will be the clip they show before she wins her Oscar.”

And Nicola Christie, writing for the Independent, predicts that this one’s “going to go down in history for the way it tells a musical tale on the big screen.” Hooper’s “reinvented the movie musical and created a whole new generation of Les Mis lovers. It’s a dream nobody could have dreamed.”

Updates, 12/9: “For fans, this is exactly how the story of Jean Valjean’s transformation from thief to saint should be delivered: smothered in bombast.” Mark Keizer for Box Office: “But when Hooper carts out the shaky-cam, wide-angle lenses and vertiginous crane shots, he risks making this state-of-the-art Les Misérables a triumph of construction over character. Hooper’s pursuit of crowd-pleasing scale occasionally leads him to overplay his hand, but all is forgiven by the next musical distraction. It’s all visual excess tampered by his reluctance to dig too deeply into the musical’s politics and religion—which for a worldwide audience is exactly what they want.”

The film closes with a “moving and spectacular finish, which will leave audiences floored,” grants Rodrigo Perez at the Playlist. “The rest of the film, however, is just a little bit overcooked.”

“When it all comes down to the singing, the communication of these grand, sweeping passions in song, Les Misérables connects and connects and connects again, and on that level, it has to be called a triumph,” declares HitFix‘s Drew McWeeney.

Updates, 12/10: “The tasteless bombardment that is Les Misérables would, under most circumstances, send audiences screaming from the theater,” writes David Edelstein in New York, “but the film is going to be a monster hit and award winner, and not entirely unjustly. After 30 or so of its 157 minutes, you build up a tolerance for those it’s-alive-alive-alive! close-ups and begin to admire the gumption—along with the novelty of being worked over by such a big, shameless Broadway musical without having to pay Broadway prices. The authors (there are four credited screenwriters) have pared down Victor Hugo’s great wallow of a novel to its dumb, pious moral (Christian forgiveness always wins, though you might not live to break out the Champagne), but the show has been audience-tested for decades and defiantly holds the screen, much like its French revolutionaries at the barricades.”

“I grew up listening to Les Misérables,” Alison Willmore confesses—her choice of wording, mind you—at Movieline. “These songs… are permanently etched in my psyche, and I am as far from being able to look at this material with critical distance as a highly trained stage star is from an actual consumptive 1800s French urchin. That said, can we admit that Les Misérables is an absolute beast of a musical? It faces the impossible task of compressing Victor Hugo’s 1500-page novel into three hours… Even at a generous running time that matches this season’s other giant award candidates, Les Misérables seems like it’s in a hurry, skittering from one number to the next without interlude…. But even if this isn’t a great screen adaptation of the musical, there’s no resisting the ending, which pairs the film’s two brightest stars and then has everyone join in on a reprise of ‘Do You Hear The People Sing?’ Say, do you hear the distant drums? Maybe not, but at that moment the voices coming from the screen and the tune they’re crooning are rousing enough to draw a few tears.”

Updates, 12/12: Calum Marsh, writing for Slant, finds that “the worst quality of Les Misérables‘s live singing is simply that is puts too much pressure on a handful of performers who frankly cannot sing.” What’s more, the film comes off as “an elaborate demo reel for [Hooper’s] tics as self-styled auteur. Those who’d considered the milquetoast King’s Speech an inoffensive but largely anonymous-looking production are here presented with a most persuasive retort—in the form of pronounced garishness. Fisheye lenses and poorly framed close-ups abound in Les Misérables, nearly every frame a revelation of one man’s bad taste; the best that can be said of the style is that it’s deliberate, which at least distinguishes it from Hooper’s work to date. What’s frustrating is that the world of the film is, outside of how it’s actually shot, magnificently realized, the filth-lined streets of early 19th-century France brought to life by the capable production design of Mike Leigh regular Eve Stewart (whose work on Leigh’s Topsy-Turvy seems the best precedent).”

For Glenn Kenny, writing at MSN Movies, “as someone whose taste in show tunes is more aligned with the era of Ziegfeld and the Schuberts than that of the super-productions of Cameron Mackintosh (this and Miss Saigon are two of the theatrical impresario’s biggest), I don’t get much out of the songs that are, all production value aside, the things that have to sell this iteration of Hugo’s epic. But such is merely my own darn taste. Most of the show’s partisans I’ve encountered have been pretty high on the movie version. But I do wonder if the rousing choir that asks, ‘Will you join in our crusade?’ is going to be able to win many further converts.”

“Sensitive souls in search of wrenching emotion can be guaranteed their Kleenex moments; you will get wet,” assures Time‘s Richard Corliss. “But aside from that opening scene, you will not be cinematically edified. This is a bad movie.”

Update, 12/16: “If I want to understand why people are so hyped for Les Miz, where do I start?” asks Jane Hu in Slate. “Happily, that question doubles as the perfect prompt for a debate over who among the myriad performers who’ve attempted the delectable roles provided by Victor Hugo’s saga have performed them best. And so…, after countless soundtrack listening sessions and solo bedroom singalongs, I give you the answers: the definitive versions of Jean Valjean, Javert, Fantine, Marius, Cosette, and Eponine.”

Updates, 12/23: “Tom Hooper’s barge-bloat adaptation of decades-running musical Les Misérables, an advanced seminar in formal misjudgment, runs a near-interminable 157 minutes, and it’s one of those rare so-bad-it’s-pitiful movies,” writes Ray Pride at Newcity Film. “Think of the classic photographs of film directors working with megaphones: Hooper’s megaphone is the size of the Hindenburg. Oh, the inanity.”

Jim Ridley and Jason Shawhan, “two guys who snuffle without shame every time they hear the cast albums,” have “watched the new movie version with the highest of hopes. One discreetly reached for the Kleenex as the characters embraced their fates; the other reached for a musket.” Their discussion is recorded in the Nashville Scene.

Updates, 12/26: “It was the right musical at the right time.” For the Los Angeles Review of Books, Laurie Winer sketches that cultural moment in 1987: the AIDS epidemic, Reaganomics, Black Monday on Wall Street. And the show runs on. “The general perception that musicals exist to entertain, to distract and soothe us, is not only a simplification; it is a misunderstanding. Since its birth, the musical has been asking us to consider, as Les Miz does, what our purpose here on earth might be, and it has done so in complex, often dark ways.”

Also in the LARB, David Ehrenstein: “That a novel as enormous as Les Misérables possesses zeitgeist in perpetuity may seem unusual. But its continued impact likely derives from the way this epic tale has been boiled down, in the popular imagination, to the Valjean/Javert confrontation, with the fates of the other characters served as emotional side dishes. And its the notion of fate, with its obvious religious underpinnings, that distances a social reformer like Hugo (who was a Royalist in his youth) from an otherwise similar novelist-cum-muckraker, Charles Dickens. Les Misérables gives readers an emotional rollercoaster ride with a patina of social consciousness that keeps the political at a polite distance. One can appreciate the book’s humanist political message but, make no mistake: the story’s shameless melodrama is what has kept this story told and retold. It’s a story, not a tract.”

“Some stage musicals just aren’t meant to be movies,” argues Dan Callahan in the L.

“As he showed in The King’s Speech and in the television series John Adams, Mr. Hooper can be very good with actors,” writes Manohla Dargis in the New York Times. “But his inability to leave any lily ungilded—to direct a scene without tilting or hurtling or throwing the camera around—is bludgeoning and deadly. By the grand finale, when tout le monde is waving the French tricolor in victory, you may instead be raising the white flag in exhausted defeat.”

“Hooper’s greatest failure in directing it is an intermittent unwillingness to trust the raw power of the material or his richly appointed setting,” finds the AV Club‘s Tasha Robinson.

Tyson Kubota for Reverse Shot: “At times, the film feels like a highly self-conscious attempt to plot a new direction for the musical genre—one that repudiates the trappings of live theater in favor of ‘realistic’ visuals and an insistence on ‘truthful’ performances, despite the toll these decisions take on the music itself. It’s hard to blame Hooper for trying; all musicals these days are meta-commentaries on a form that, like the Western, survives only as a spectral genre, its genes long since spliced into other formats and places, like music videos, the lip-synched spectacle of pop concerts, and Bollywood. Despite the film’s specific failings, its narrative arc—from confinement and tragedy to truth, love, and redemption, accompanied by the stirrings of revolutionary change—is still moving in its epic sweep and blunt thematic engagement. Les Misérables presents a simpler world, rich in human feeling and free of irony. Questionably grandiose aesthetics aside, the film seems apt for a cultural moment that collectively yearns for spiritual sustenance even as it tries to deny these impulses, locating a shared cliché of ‘authenticity’ and holding it close to heart.”

The Los Angeles Times‘ Kenneth Turan warns that “if unashamed, operatic-sized sentiments are not your style, this Les Miz is not going to make you happy.”

Jason Bellamy presents a review to the tune of “Master of the House.”

Movieline‘s Frank DiGiacomo talks with Hooper “about his reasons for making the movie and the challenges of pacing and editing a film that is essentially sung through from beginning to end. He also addressed criticism that he relied too heavily on close-ups in the film, divulged Eddie Redmayne’s technique for attaining such exquisite sadness in his performance of ‘Empty Chairs at Empty Tables’ and answered the burning question of the day: whether Anne Hathaway or Hugh Jackman is a bigger musical geek.”

Updates, 12/30: Ignatiy Vishnevetsky in the Notebook: “While unheard of for a big-budget production, live-sung musical numbers are nothing new—and lately, they’ve become more and more common. The same device is used for Kylie Minogue’s musical number in Holy Motors—and result is more effective than any anything in Les Misérables. It’s an interesting case of a technique becoming technologically outdated and then returning decades later as a deliberate stylistic device.” History follows.

“I was unprepared, having missed Les Misérables onstage, for the remarkable battle that flames between music and lyrics, each vying to be more uninspired than the other,” writes Anthony Lane. “The lyrics put up a good fight, but you have to hand it to the score: a cauldron of harmonic mush, with barely a hint of spice or a note of surprise…. I screamed a scream as time went by.” But Adam Gopnik, also writing for the New Yorker, “will confess myself an unashamed, weepy fan of the Schönberg and Boublil adaptation—I use the verb ‘confess’ because it is the kind of European-bombast musical that I normally hate, the kind that pretty much killed off the real, more informal and comic American kind of musical that it spawned…. I had the nice assignment, a few years ago, of writing the introduction to Julie Rose’s masterly translation of the book, which caused me to reflect at length on why this novel, improbably long and gassy in spots, still mattered so much to so many.” And of course, he revisits those ideas.

David Haglund: “Earlier this week in Slate, Rachel Maddux attempted to explain why tweens—or, as we called them when I was one, children—love Les Misérables, despite the musical seeming, on paper, ‘decidedly un-kid-friendly,’ what with its centuries-old, epic source material and its emphasis on poverty and prostitution and so on. Among the reasons Maddux cites: the ‘show’s overwhelming emotional bigness,’ the way its characters are all ‘straining or scrambling toward some unseeable future’ (like, e.g., someone on the cusp of adulthood), and the ‘peephole’ the show provides into ‘grown-up stuff.’ Having seen the musical when I was 9, on its first U.S. tour, all of those reasons sound right to me. But there’s another one, perhaps more particular (but not unique, surely) to boys, which only hit me when I watched the new film adaptation: Jean Valjean is a superhero.”

Also in Slate, Dana Stevens wonders out loud, “given that I’ve never seen a stage production of Les Misérables and probably wouldn’t enjoy it if I did, am I still allowed to say that this show could surely have been done better justice than this movie does it?”

“This movie is by definition hobbled, with no chance of equaling Raymond Bernard’s exquisite and resonant 1934 version of the novel, which unfolded over five luxurious hours,” writes Michael Koresky for Film Comment. “The stylistic elegance and visual coherence of that early French cinema adaptation have been traded in for an all-out sensory assault. As The King’s Speech’s Merchant-Ivory-meets-Jean-Pierre-Jeunet style suggests, Hooper is more capable with actors than with space and there’s no dancing, thank God. Ultimately the film’s choppy, camera-goes-anywhere approach works well in translating a play that was never all that interested in the movement of bodies anyway—only their martyrdom.”

“When Les Misérables is good, it is very, very good, and when it is bad, it’s usually because Russell Crowe has opened his mouth,” writes Kimberley Jones in the Austin Chronicle. Counters Robert Horton in the Herald: “His singing voice strains at the demands of the role, but he does have presence.”

Goldy in the Stranger: “You are going to cry, goddamnit, even if the ghosts of the dead have to come back for the finale and hand-massage your tear ducts. Which they do.”

Kate Kellaway talks with Hooper for the Observer. Interviews with Jackman: Kyle Buchanan (Vulture) and Jesse Dorris (Time). And one more from Vulture: “Was Les Misérables any good at all? Amanda Dobbins and Kyle Buchanan will now hash it out.”

Update, 1/18: “Granting that Jean Valjean’s saint-like quest for personal salvation forms the redemptive core of the story,” writes David Hancock Turner for Jacobin, “what if the global popularity of this work also echoes the perennial frustration with government’s interminable persecution of innocents and its obsessive zeal for crushing liberatory movements? The perennial hostility of critics would then remind us more of the nervous murmurs and outright hostility of elites whenever the masses begin to congregate, build barricades, camp out and demand a better world. The tears of the audiences would not remind us that the ‘people’ are easily conned into weeping over a melodramatic spectacle that apes the gospels, but perhaps allows a vicarious vision of rebelling against unjust rule while remaining true to desire and love.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.