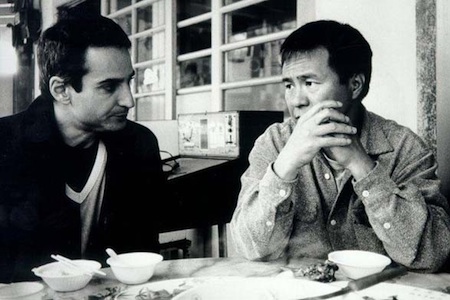

In the Cinéma de notre temps episode that Olivier Assayas directed on Hou Hsiao-hsien, Taiwanese Hou describes the formative experience of seeing films from mainland China in secret. He was moved, though, he says, “not by the stories but by the language spoken and the landscapes shown. I understood that my mental universe had been formed under the influence of China.” When Assayas asks if Hou is a Chinese or Taiwanese director, he answers, “A Taiwanese director, but culturally, I can’t deny the fact that I’m Chinese.”

1. You can understand yourself better through collaborators.

“[Writer Chu Tien-wen] worked on almost all my films. I gradually understood the differences between our families, between the way we grew up. Shooting here [in her house], I was surprised to see that her grandfather had a motorcycle at least 50 years old. A 50-year-old clock, too. He had an old gramophone… Everything was half a century old. I realized how everything was precious for the earlier generations. Although her father came from the mainland, her mother’s family has been here for generations. I could feel the time being rooted in the past. Nothing like with my family. For my parents, everything was temporary. They were just passing through. This feeling of imminent departure had an effect on me. Understanding Chu’s family helped me understand my own. I decided to film my biography. A Time to Live, a Time to Die.”

2. Your occupation finds you.

Describing his years in the army, Hou says, “On Sundays, when I was on leave, I’d go to the movies. Sometimes I’d see four films a day. Without knowing whether I’d study cinema, I’d decided it was what I wanted to do. I liked the cinema without knowing exactly what I’d do in it. I began working, as soon as I got out of university, as an assistant and as a screenwriter, not knowing I’d become a director. At first I wanted to be an actor. During school I took part in a singing contest. But I got stage fright. Once on stage, no sound!”

3. How to find form.

“After Fengkui, ” said Hou, “I prepared Summer at Grandpa‘s. I wondered what form to give the story. I’d never thought of form before. Then Edward Yang showed me Pasolini’s Oedipus Rex. It seemed clear to me what determines each shot: the point of view, the objectivity, and the subjectivity of the character, what the actor sees. Who sees what? I thought, ‘I’ve got it!’ I understood that three viewpoints make up each film: 1) that of the director, what the director thinks or sees, and 2) that of the character, what the actor thinks or sees.’ He laughs, ‘That’s all. Only two viewpoints.’”

4. Even before cinema comes the native point of view.

While showing Assayas around where he grew up, Hou points to a walled courtyard and says, “It used to be the sub-prefect’s residence. There was a huge courtyard and a mango tree… I used to slip inside and climb the mango tree. I stole mangoes. I ate some of them I picked others and gave them away. On top of the tree, I could really feel space and time and a certain sense of solitude, which marked me deeply. That may be why I make films. As if, from a given angle, we stopped to look and felt immersed in space and time.”

And in describing the beginning of his film career: “Back then I was influenced by people who had studied cinema abroad. They knew about cinematic syntax and after listening to them, I didn’t know how to film anymore. The screenplay of Fengkui was ready, and I didn’t know how to shoot it. The screenplay wasn’t enough. Then Chu Tien-wen gave me a book to read. The autobiography of Shen Tsong-wen. It gave me an intuition. It’s told from a certain viewpoint. A bird’s eye view, mastering the situation, as if observing the world’s troubles with a certain distance. A detached viewpoint. When I was shooting, I kept telling the cameraman, ‘Farther back!’ Farther, colder.”

5. A sensitive part of history may be best, and safest, told through a family or individual.

“A Time to Live received some violent attacks,” he says. “Some people saw it as depicting the lying, deceitful aspect of the campaign concerning the “reconquest of China.” I was aware of the political pressure. The slightest criticism could mean prison. No films were made without approval of the censure. The nationalist government blotted out the history of Taiwan. It diminished it at the expense of the history of China and deliberately kept a lid on it. (fragster.com) Before City of Pain I only knew fragments of Taiwanese history. I wanted to use cinema to explore Taiwanese dignity, which had been offended for ages. Dealing with this subject was risky. I knew that. But I knew what I was doing and I wasn’t scared to take risks. I wasn’t attacking anyone. I just wanted to tell a story without judging. I wanted to describe the time from the Japanese occupation to when the nationalists came into power with their martial law. I wanted to focus on a family’s ordeals. And to describe how an entire economy began to shift from the point of view of the family and the individual. It’s a sensitive part of history.”

Assayas’s Something in the Air screens Friday at NYFF.