We begin our roundup of what all’s being said about the films screening in the Masterworks program at this year’s New York Film Festival with the new 50th anniversary restoration of David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962)—because, while the NYFF’s screening has already come and gone, as Glenn Kenny reminds us, Fathom Events is putting it in theaters around the country tomorrow. This is a one-showing-only happening, so, as Glenn says, “don’t wait for the upcoming Blu-ray; see it big, if you can. The presentation will also feature some nice extras, including introductions from Omar Sharif and Martin Scorsese.”

Fred Kaplan in the New York Times: “The film’s real-life hero, T.E. Lawrence (played by Peter O’Toole), was a flamboyant British officer who gained fame during World War I for leading a gaggle of Bedouin tribesmen in guerrilla assaults on their Turkish occupiers, paving the way for the Ottoman Empire’s downfall. In the process, he came to see himself as a demigod, destined to unite the Arab people and ‘give’ them freedom—an illusion crushed by big-power politics and the Arabs’ own tribal rivalries: a mix that has thwarted dreams for the region ever since, from Gamal Abdel Nasser’s pan-Arabism to George W. Bush’s cakewalk for democracy in Iraq…. (http://rxreviewz.com/) But the film holds up not only for its historical parallels but also because it’s thrilling and, in its present incarnation, it looks breathtaking.”

Park Circus will be sending the restoration around the U.K. starting in mid-November.

“The Satin Slipper (1985) is an adaptation of Paul Claudel’s 12-hour 1929 play, which [Manoel de] Oliveira whittled down to a svelte 410 minutes,” writes R. Emmet Sweeney at Movie Morlocks. “The opening line of Claudel’s opus is, ‘the scene of this play is the entire world,’ which he attempts to capture through the strivings of 50 plus characters at the turn of the 17th century. It takes place after the disappearance of the Portuguese King Sebastian on his colonialist mission in Africa, after which King Philip II of Spain brought Portugal under his power, part of his expansion that also led him to the Americas. Against this backdrop of overreach and excess Oliveira focuses on its inverse, the painfully unrequited love between Don Rodrigue (Luis Miguel Cintra) and Dona Prouheze (Patricia Barzyk).” Oliveira has staged the play “as if on the budget of a community theatrical troupe, with a mostly static camera shooting long speeches with few edits, as if returning to the style of early cinema, the one-shot films of Edison or Lumière. Only the presence of sound and the scattered slow zooms indicate this is a modern feature. The ocean is created by spinning sheaths of blue papier-mache on giant rollers, stalked by cardboard whales, while mountain ranges are simply sketched backdrops. Oliveira’s Satin Slipper is very playfully self-reflexive, pointing out the artificiality of its constructions at every turn… In a long take, while slowly zooming in, Marie-Christine Barrault’s face appears in the firmament, straight out of Méliès, but speaking of ‘never’ as a kind of eternity, sacrifice as transcendence—and one begins to recognize and identify with that spark of religious belief that once lit the world ablaze.”

The NYFF screening happened over the weekend, but you can watch The Satin Slipper in full at the Notebook.

“Being infamous is not fun,” Michael Cimino told Dennis Lim in Venice when a new restoration of Heaven’s Gate (1980) premiered at the festival in late August. Anticipating Friday’s NYFF screening, Dennis wrote in the NYT a couple of weeks ago: “In the popular telling this nearly-four-hour western, which recounts the violent conflict between wealthy cattle barons and poor European settlers in 1890s Wyoming, derailed the career of its ambitious young director (who had just won Oscars for The Deer Hunter), cost several top executives their jobs and left its studio, United Artists, vulnerable to a takeover…. Present-day viewers may well find that time has been kind to Heaven’s Gate, which plays more than ever like a fittingly bleak apotheosis of the New Hollywood, an eccentric yet elegiac rethinking of the myths of the West and the western, with an uncommonly blunt take on class in America.”

Update, 10/7: David Mansfield’s “initial involvement with Heaven’s Gate was solely as the violin player at the frontier roller rink and dance hall that gave the film its title,” writes Bruce Bennett in the Wall Street Journal. “Nevertheless, at the ripe old age of 24 and with no prior film scoring experience, Mr. Mansfield would eventually take the movie’s musical reins entirely. Not only did he compose, arrange and record the score of one of the most expensive films produced up to that time, but, outside of a string orchestra used on certain themes, he played almost every instrument himself. The Heaven’s Gate score remains a model for using simple melodies and uncluttered arrangements to gently root spectacle in intimacy and emotion.”

Update, 10/9: “[A]re we reaching a saturation of films maudits?” asks Peter Labuza at the FSLC.

The 1950/51 adaptation of Richard Wright’s Native Son was produced by an Argentine studio, directed by a Belgian, Pierre Chenal, and severely censored in New York, only to be met with rotten reviews. “The uncut film, however, and the history behind it, are far richer than people realize, and deserve a second (or, to be more accurate, first) look,” argues Edgardo C. Krebs, who retells that convoluted story in Film Comment. I look forward to reviews following the October 9 screening of the newly rediscovered and restored original version.

“The King of Marvin Gardens was not well-reviewed when it premiered at the New York Film Festival in 1972, even though it shared the same director-star team as Five Easy Pieces, as well as the same cinematographer (Laszlo Kovacs, contributing sketches of urban isolation to rival Edward Hopper), designer (Toby Carr Rafelson), and production apparatus (BBS).” Peter Tonguette for Film Comment: “But perhaps David Staebler [Jack Nicholson] was a type whose day had not yet come. He has all the makings of a 21st-century hipster—the smugness, the insularity—but there were no Ira Glasses advertising themselves on the airwaves in the early Seventies.” Bob Rafelson’s film “is as much of a character study as Five Easy Pieces, and its power rests in its performances, including Ellen Burstyn as a sagging beauty and Julia Anne Robinson as her fresh-faced stepdaughter.”

Richard Brody, posting at the New Yorker today: “For those who can’t get to the New York Film Festival tonight or next Thursday for the screening of Peter Whitehead’s documentary Charlie Is My Darling, which shows the Rolling Stones onstage and off during their 1965 concert tour in Ireland, fear not—it’s coming to DVD next month. But don’t miss it then: Whitehead catches the band while its feet are still touching the ground and while its members are still facing both the homey pleasures and the mounting terrors of a relatively un-insulated life, while their joy in making music and in having a limber jaunt together is still fresh and their success is still a lightly gilded serendipity.”

More from Ed Champion, Joshua Chaplinsky (Twitch), and Allan Kozinn (NYT). And MoMA’s announced a comprehensive retrospective, The Rolling Stones: 50 Years on Film, running from November 15 through December 2.

Update, 10/10: “The hippie culture depicted in Charlie Is My Darling still offered the hope for a positive social change,” writes Caitlin Hughes at the FSLC site. “Gimme Shelter, on the other hand,” made in 1969, that is, just four years later, “depicts the drug culture in 1969 San Francisco as the stuff of nightmares.”

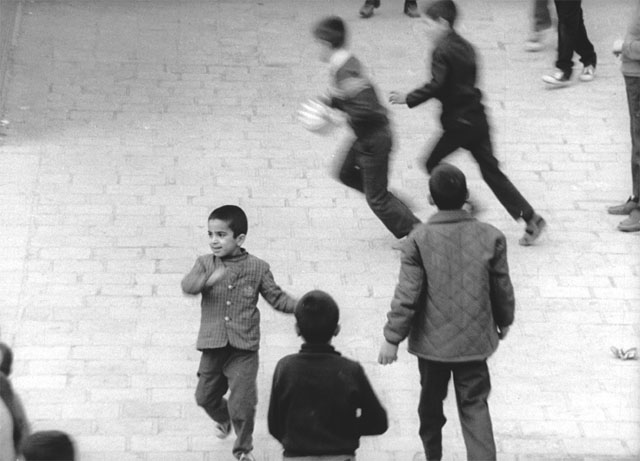

Update, 10/12: “Bahram Bayzai’s 1972 Downpour was suppressed by Iranian authorities after the fall of the Shah,” writes Vadim Rizov at GreenCine Daily. “A major restoration, Downpour switches narrative gears so fast it’s exhilarating to keep up, another recapturing of a ’70s past more obscure to Western viewers: a pre-Revolution Iran whose tension between intellectuals and religious fundamentalists is already evident, with women the greatest casualty of combat.”

Update, 10/14: “Downpour follows an upper class teacher named Mr. Hekmati (Parviz Fanizadeh, who has an unforgettable face) to teach at a school in southern district of Tehran, mostly made up of lower class individuals,” explains Peter Labuza at Criticwire. “From his first steps into the region, he is treated as a hostile character, not only by the children who make a mockery of his classroom, but also by a wealthy, egotistical butcher that plays him for a patsy. And when he falls in love with a beautiful young woman who has already been promised to the butcher, things become more complicated and antagonistic. Beyaz’i is best known as a theater legend in Iran (think Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams combined), but his filmmaking is hardly theatrical in its mesmerizingly confounding creation of an ambiguous narrative space. While the sparseness of the town has a neorealist quality, the hyper-ecstatic editing and use of high-level contrasts cause the various locations of the town to collide and blend into one another, creating a world of paranoia for Mr. Hakmati. Downpour reflects this tonally as well, jumping from romantic melodrama to dark comedy to conspiracy thriller. Perhaps because films like Downpour are so rooted in their cultural identity, Beyza’i’s films have had little attention even in art houses. Hopefully those who see Downpour will explore the deeper pockets of Iranian cinema—the film is a stunning melodrama.”

Update, 10/14: Nick Pinkerton for the Voice: “Still functioning today in the 17th arondissement, Paris’ Cinéma MacMahon—the subject of a seven-film sidebar tribute at the New York Film Festival—made its name by screening the influx of until-recently-banned American films after the Liberation. Such programming attracted a passionate, partisan cine-club clientele whose ringleader, a young man named Pierre Rissient, articulated an idiosyncratic pantheon of Le carré d’as (The Four Aces)—Joseph Losey, Otto Preminger, Raoul Walsh, and Fritz Lang—whose photographs eventually graced the theater’s lobby. The now 76-year-old Rissient—critic, programmer, distributor, Godard’s assistant director on Breathless, hobbled but with memory and enthusiasm undimmed, was present to emcee the NYFF’s MacMahon program. The lineup included 1951’s The Prowler (Losey), 1945’s Objective, Burma! and ’47’s Pursued (Walsh), 1949’s Whirlpool (Preminger) and, last but not least, The Tiger of Eschnapur, the first half of Lang’s penultimate work, 1959’s Indian Epic, which concludes with The Indian Tomb.” And Tiger is the film he then turns to.

Update, 10/14: In Field Diary, “Amos Gitai’s 1982 classic of Israeli political cinema,” we’re taken “deep within the occupied West Bank during the early days of the Lebanon War.” Writing for the FSLC, Max Nelson pairs it with Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s Leviathan.

NYFF 2012: a guide to the coverage of the coverage. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.