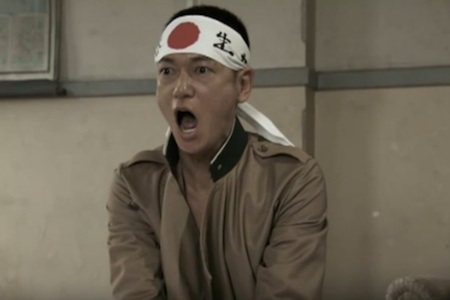

It had been 40 years since Koji Wakamatsu stirred the pot at Cannes with a film titled Sex Jack, and Koji Wakamatsu the flamboyant entertainer who fathered Japan’s softcore ‘pink cinema’ genre had long been replaced by Koji Wakamatsu the political analyst when Keyframe caught up with him to talk about his latest, 11/25 The Day Mishima Chose His Own Fate. Wakamatsu, always a nonconformist (and the subject of a Kevin Lee video essay viewable here), has long opposed the establishment and government, dwelling on Japan’s unknown past. Always visually precise and merciless, in United Red Army Wakamatsu explores the political background that led to the Asama-Sansō incident and the self-destruction of the Japanese radical left; in Caterpillar (nominated for the Golden Bear at the 60th Berlin International Film Festival) Wakamatsu studies the fate of body and mind traumatized by war-zone experience and critiques right-wing militarist nationalism during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II. His latest, 11/25 The Day Mishima Chose His Own Fate, focuses on an incident that shook the Japanese society; the so-called Ichigaya incident (11.25.1970) that resulted in the ritual suicide of acclaimed novelist and political activist Yukio Mishima and one of his followers.

Keyframe: How did you come up with the idea for this film?

Koji Wakamatsu: I first thought about it when I was shooting United Red Army, during one the scenes when the army marches in a very strong blizzard. We shot this scene in a real blizzard by the way. Red Army was a formation of left-wing extremists; but I knew that, at that time, there were right-wing activists as well, young people who wanted to change the society just as much, even at the cost of their own lives. I felt that portraying only one side of the whole spectrum wouldn’t be right and that I should at least try to depict both extremes. The idea for a film about the Shield Society appeared. First it was just an innocent joke; I’d tell my actors from United Red Army that my next project will be on the extreme right, for a change. But I knew that making these films in a row will be rather hard on me, so in the middle, as a sort of easy play, I shot Caterpillar. Both United and the latter had a very good audience and attendance that provided enough money for my next project, which was 11/25, dedicated to the legendary figure of Mishima. I also managed to finance two shorts from the gross: Cayenne Blue and Millennial Rapture.

Keyframe: You made this film soon after Japan suffered a terrible series of natural disasters. Did these circumstances make it a special experience?

Wakamatsu: No. Even though my own hometown of Wakuya was torn to pieces by the tsunami. But as long as we live on earth, natural disasters will be a part of our reality, that is nothing exceptional.

Keyframe: I have read that making the film was very emotional, and at times even dangerous?

Wakamatsu: There are other films about Red Army, but in all those films the names have been changed. I don’t do that. In my film all the protagonists are called exactly what they were in real life, and the same refers to Mishima. My colleagues and acquaintances tried to warn me; they were sure that if I leave the names intact, I will become a target for some radical right-winger. I said: ‘Well, if this is what they want to do—fine.’ I think my film tells the story of both right and left wing, covers all the aspects of the political spectrum. I believe I am trying to do something good for the society, so there’s no need to feel ashamed or live in hiding. After seeing the film, the right wing thanked me, instead of assassinating me. Not only they went to the cinema and paid for the tickets but also helped sell them! I believe that happened because my intention was genuine.

Keyframe: Your visit to Cannes happens in a symbolical moment: in a way this is an anniversary of the Sex Jack screening. How does it feel to be back here after so many years with yet another film that is politically involved?

Wakamatsu: It doesn’t carry any special meaning to me, it’s a coincidence of no significance. It was 41 years ago when I was in Cannes. If there was anything special in that visit it was that on the way back we stopped in Palestine to make a documentary Sekigun-PFLP: Sekai Senso Sengen (The Red Army-PFLP: Declaration of World War). And because of that I was labeled a terrorist and claimed persona not grata by the United States and Russia among others. The Japanese government has questioned me 15 or 16 times. It that sense, it was quite a memorable visit.

Keyframe: Mishima tells a story that is driven by and based on a deep sense of comradeship. Such a concept is not necessarily obvious for someone from outside the Japanese culture.

Wakamatsu: To put it very simply: The Japanese culture is not individualistic, it focuses on the community. Whatever we do, we always consider our neighbors, family, and friends. If your dinner turns out really delicious, it is natural to offer your neighbors a taste, to share. The differences between Japan and Europe or United States might be also rooted in religious concepts of Christianity and Buddhism. And therefore, some behaviors, or rituals—like seppuku, one of the main subjects in the film—are hard to comprehend for a viewer from outside of our culture.

Keyframe: Mishima is played by actor Arata is very well known in Japan. Casting stars in not really your style…

Wakamatsu: The main reason is that he was also in United Red Army and I got to know him as an extremely hard worker and somebody who’s able deliver great performance with consistency. I’m this type of person that feels strong gratitude and obligation to repay those who gave something to me. Arata was very well know already, yet agreed to do the shoot on my terms and follow my method. He came alone, without any manager or personal assistant. On the set I use no make up, have no script girl or secretaries—he had to accept that. I very much like observing my actors when I work. There were several candidates for Mishima’s part, but finally I chose Arata. Looking at the film only reassures me that I made the right choice. I never cast stars to attract a bigger audience. To me it doesn’t matter if it’s Arata or an amateur. As long as one has a heart, he can act. If making films was about attracting people with star power I wouldn’t be a director anymore.

‘To put it very simply,’ said Wakamatsu, ‘the Japanese culture is not individualistic, it focuses on the community. Whatever we do, we always consider our neighbors, family, and friends. If your dinner turns out really delicious, it is natural to offer your neighbors a taste, to share. The differences between Japan and Europe or United States might be also rooted in religious concepts of Christianity and Buddhism. And therefore, some behaviors, or rituals—like seppuku, one of the main subjects in the film—are hard to comprehend for a viewer from outside of our culture.’

Keyframe: The only female figure in the otherwise masculinized film is Mishima’s wife. She’s spoken of rarely, appears in one scene, and barely has one line. Why have you decide it to introduce this character in your project at all?

Wakamatsu: I believe that the very consciousness of her existence was necessary for the film. During the research stage before we started shooting, I found many proofs of how wives were influential in the Shield Society even though they were outside of it. For example, they were present during training camps, giving pep talks to the trainees. Also in the household, her presence was natural. In Japan, wives’ position is behind their man, in the background. Mishima’s wife would’ve never stepped out; she’d support him silently, like she did. That is the cultural thing that might be hard to comprehend for westerners.

Keyframe: Is Mishima’s seppuku clearer to you after making this film?

Wakamatsu: In Japan, there was a lot of buzz caused by Mishima’s suicide, people asking themselves: ‘How?’ and ‘Why?’ The reactions were quite ambiguous. The public reacted differently, according to their own understanding and imagination. I, of course, based the film on mine. Mishima has chosen the venue and time of his own death. The date, the 25th of November, was when one of his close friend’s from the University of Tokyo committed suicide. He was involved in a financial fraud, couldn’t get out of it, and felt so cornered and hopeless he’s decided to take his own life by hanging himself.

Keyframe: What is your personal opinion on Mishima’s decision?

Wakamatsu: At that time, when it happened, I thought it was simply stupid. And bringing those young boys, his ‘toy soldiers’ along… I thought that Mishima, an accomplished writer and well-established citizen, eventually went insane. But as time passed, my opinion was evolving. I went through many document, also his writings about that event. I also sometimes drink sake with one of the Shield Society members who survived that action. Now I think he’s a phenomenon.

Keyframe: What was pinku eiga to you and why, even though you are strongly associated with the genre, did you stop making such films.

Wakamatsu: I was the first director of pink cinema, and everybody else followed me and copied what I came up with. But their imitations were focused only on showing naked women, sex scenes and so forth. After it all started, the pink cinema went down the drain and became the mainstream. There were so many pink films around that I didn’t feel it was interesting for me to continue that path. If you compare pink cinema from the time when I was active in that genre and contemporary pinku eiga, they are entirely different. All the directors who made pink films back then have disappeared with the exception of Mr. Takita, who became very successful; his film “Departures” is known around the world. To others pinku eiga was just about making money. They are too scared to be anti-establishment. Making a film is to me throwing a stone at the establishment, and what happened to pink cinema is that it became a conformist entertainment.

Keyframe: You are not Japanese government’s favorite. Your every project is yet another struggle…

Wakamatsu: The government does not recognize my films because they in a way rebuild this part of Japanese history they’d like to forget about. My work is most problematic especially for the Cultural Agency. They have a budget to use for subsidizing film initiatives. But they wouldn’t give any of it to me, even though I asked them many times. They’ve funded films with no value, but not mine. Probably that is because I am very straightforward with them, and do not hide that I consider bureaucrats working there complete and utter idiots. I don’t think my situation will ever change, mostly because of the subjects I choose. They wouldn’t give a single yen for a film about Red Army or Mishima.

Keyframe: You are considered as the godfather of some Japanese filmmakers’ careers, e.g. Banmei Takahashi. Is mentoring younger directors important to you?

Wakamatsu: It is true that many young filmmakers started their professional career on my set or thanks to my recommendation. But it was them who came to work for me, not me who asked them to. Of course, I can help them, give some assistance or mental support. But the truth is they are my competitors, in other words: they are my enemies. But by creating my own enemies I become more enthusiastic. If one of them makes a really good film, that only motivates me to be even better. The directors I mentored are to my best, most inspiring, competitors. In the mainstream I don’t see anyone who I could consider as such.

Keyframe: You are a very precise author, whose art is so particular, that sometimes it might come across hermetic.

Wakamatsu: I think in Japan, and anywhere else in the world, there are many mysterious things, and what I do is simply turn them into images. My work is sometimes difficult, but I am always staying true to myself; my films are mine, and nobody else’s. Each person is different, in terms of the looks, but particularly in terms of thinking, there are no identical human beings. For example: this might seem water to you [points at large bottle of Perrier] but there may be someone who doesn’t perceive it as transparent, but red. It’s not us longing to be each other’s clones, it’s the authorities, who try to make everyone as identical as possible.