There’s a scene from the movie Tulpan, a narrative film about Kazakh herders on the Central Asian plains, in which a young apprentice herder finds a pregnant goat in need of help. The character has never birthed a goat before; for him it’s a rite of passage. That, plus the established plot line of a recent epidemic of stillborn goats, give the scene its narrative suspense. But as the scene goes on we forget that there’s even a story. This moment unfolds in one continuous 8-minute shot, and we are transfixed by its spectacle. It feels like we’re watching a pure documentary moment in all of its raw immediacy. At the same time, it is a movie: we note the remarkable camerawork, both in its steadiness and selectivity in what to focus on, serving as a midwife to a cinematic moment being born. We might also ask ourselves what experience the actor has in birthing goats, how much his anxious, inexperienced demeanor is really just an act.

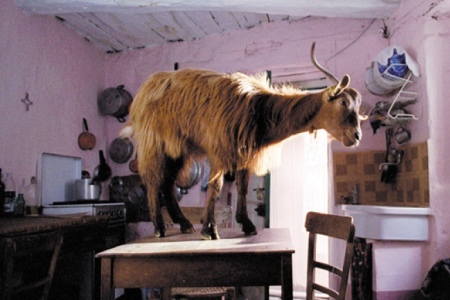

A baby goat also stars in Le quattro volte, a poetic documentary that follows four seasons in an Italian farm village. Once again, we watch a helpless new creature and feel we are witnessing pure observational reality, a baby goat’s first moments of life, as it learns to stand, feeds from its mother for the first time, and encounters other kid goats. The camera dotes on its nascent existence, formless and carefree. But then something peculiar happens: A scene follows a herd of goats passing through a woods, and the kid emerges, left behind and lost. We worry for the kid, but as the sequence unfolds, with one immaculately staged shot after another of the kid lost and roaming, we realize that it has become something of a child actor. An observational documentary has transformed into staged drama, with human emotion imposed on an animal form.

Unlike Tulpan or Le quattro volte, the documentary Sweetgrass hardly focuses on a single animal or a human protagonist. It’s more interested in capturing the experience of sheepherding in its full range of sensory details. What comes through in shot after shot is the filmmakers’ way of seeing and hearing, revealing visual and aural patterns that approach abstract art. You would assume that the simple act of observing animals would provide straightforward instance of documentary realism, but even here you feel the imposition of a human perspective, a cinematic anthropomorphism.

It seems that no matter how we look at animals, we are in the picture. It begs the question, how do the animals see us?

Kevin B. Lee is Editor in Chief of IndieWire’s PressPlay Video Blog, Video Essayist for Fandor Keyframe, and contributor to Roger Ebert.com. Follow him on Twitter.