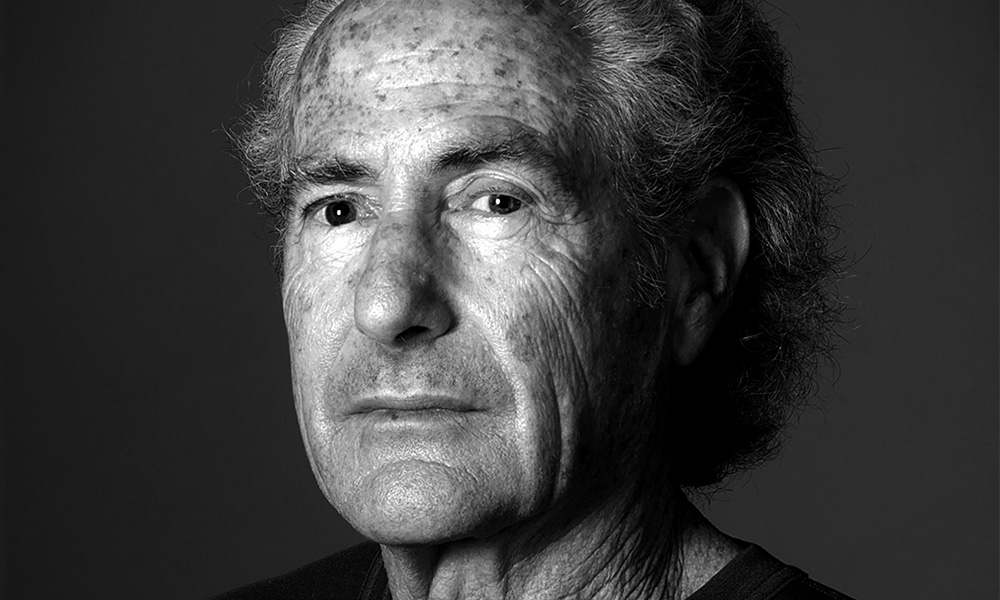

One of the most prolific and wide-ranging American writers—with more than 40 works of fiction, nonfiction, poetry and screenwriting to his name—Barry Gifford is most immediately known for his series of “Sailor and Lula” novels, one of which, 1990’s “Wild at Heart,” became the David Lynch film starring Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern, the first of multiple collaborations.

Gifford’s most personal body of work is the so-called “Roy stories,” which recall his 1950s boyhood growing up in both Chicago and various points south, including Key West, New Orleans and Havana, Cuba, and the peculiar realities of his parentage, with a Texas beauty-queen mother and an immigrant father with connections to organized crime. Much of those early years was spent living in hotels… and fending for himself.

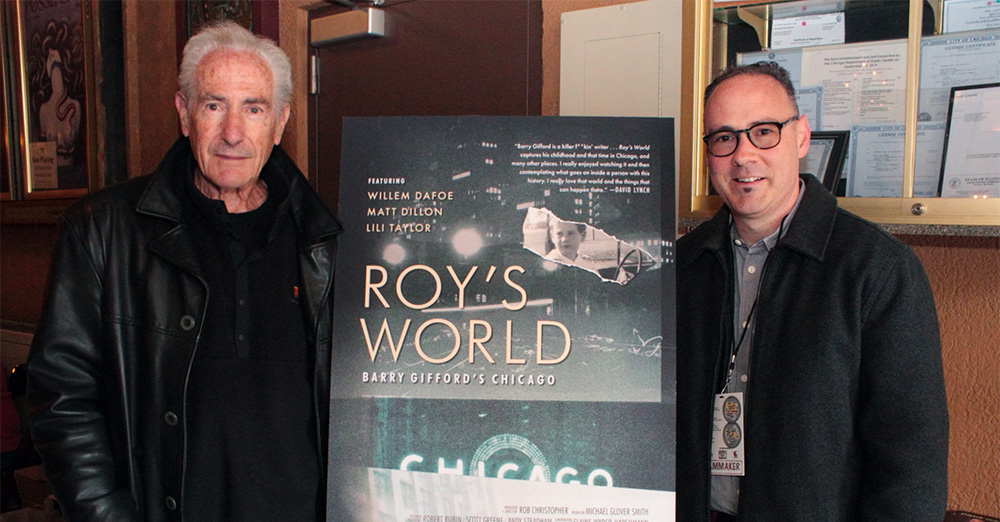

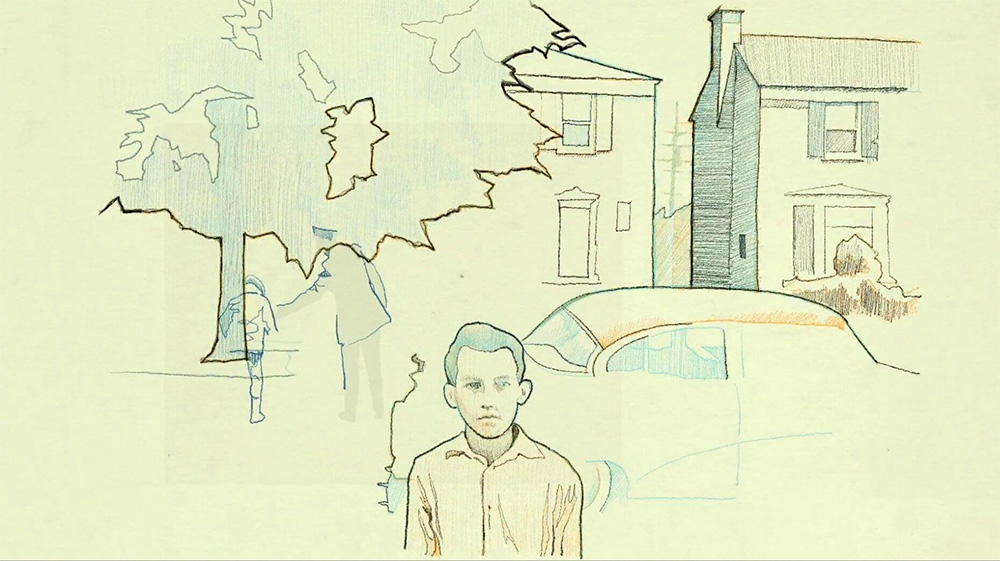

In Roy’s World: Barry Gifford’s Chicago (now streaming exclusively on Fandor), writer-director Rob Christopher employs Gifford’s own voice, and those of actors Willem Dafoe, Matt Dillon and Lili Taylor, to bring the Roy stories to life onscreen, with a generous selection from Gifford’s prose visualized through a rich array of archival footage, animated sequences and materials from Gifford’s personal trove. Topped with composer Jason Adasiewicz’s aces jazz score, these episodes conjure a lost place and time with knowing intimacy and tender detail.

Earlier this week, we caught up with Gifford, who had just celebrated his 76th birthday, at his home in Berkeley, California, to talk about the film and his life, the symbiotic nature of the Roy stories (first fully collected in the 2013 anthology The Roy Stories, naturally), Chicago and, of course, his pal David Lynch.

KEYFRAME: How did this project begin? How did Rob Christopher first approach you?

BARRY GIFFORD: He was a reader of mine and he reached out to me and asked if they could publish some of the Roy stories before they were in book form. At some point, there were a couple of people wanting to do biographies or who had written theses or whatever. I had no interest in participating in anything like that. Rob came up with an idea for a documentary, being a filmmaker himself. There have already been a couple made in Italy and France, and they were good, but with the usual talking heads. I said I wasn’t interested at all in that. As I thought about it more, I said, “Okay, but I don’t want to be in it.” Not that I wouldn’t participate, in terms of interviews or a voiceover. He came up with a similar kind of scenario and it was just a matter of figuring out how to do it. I said, “I want you to make it about Roy.” That was Roy’s World. That was the perfect title for it. He pulled off something that I never assumed would be successful.

The elements are so powerfully evocative of a time and place, which is obviously in the words, but also an incredibly deft use of archival material, sound and editing.

Rob had a special interest in Chicago. 90% of the Roy stories and the novel “Wyoming” take place in Chicago. That’s what gave him that insight and direction in which to go. Then of course it was about Roy, but who was Roy? So that led to the investigation into my history, and he was very interested in the period. The Roy stories are really the history of a time and place that no longer exist.

There’s so much memory and reflection at play, and it feels so piercingly intimate at times, even knowing as a viewer that it’s a fictionalized version of things.

That’s the point. I was never interested in writing autobiographically. The events and the place and the time, they all figure into it. My situation certainly was the largest part of it, you know, what was going on in my life. But there were always things in there that did not pertain to me necessarily. That’s why I created the elliptical structure, it’s not chronological. What I wanted it to do was create these pictures, these moments that come into your mind and you can see them. That’s why I began doing the drawings—I always was drawing from the age of about nine or 10—to accompany the stories and to illustrate some of the characters that appear in them. The drawings that I’ve done appear at the end of the story. It really seals the deal on each individual piece. Having that elliptical structure gave me all the freedom in the world.

Recently I did an interview with The Hollywood Reporter because a video game was based mostly on one of the Roy stories. There’s a character in it named Barry Gifford. The question was, how does it feel to be a character in a video game? I’ve acted in two or three movies, but this is something different entirely. They wanted me to play the role, and I couldn’t. The timing didn’t work out. I said, “I’ve never played a video game. I have no idea.” I really don’t know until I experience it. That’s one reason why I didn’t want Rob to have “Barry Gifford” in the film.

It works nicely in that you have the Roy stories, recounted in narration and with archival imagery or animation, and they flip into your personal story. At some point, they seem to merge, and I had to remind myself which was which.

Exactly. It’s really the essence of symbiosis. I gave Rob access to old home movies and photographs. It blended them together.What’s the difference between Barry Gifford and Roy? Does it matter?

Do you ever revisit what’s become of the old neighborhood?

In the few times that I’ve been back to Chicago over the years, if whatever I’m doing takes me back to the old neighborhood, that’s fine. But no, the neighborhood exists in my head, in my vision of it all. I’m not really so interested. It’s funny, though, when I went to the premiere in Chicago of Roy’s World it was interesting to sit in the audience and pay attention to what they were laughing at. Chicago was like a giant small town, and it’s still pretty much the same way. Chicagoans are a particular kind of breed, and especially in that time that I concentrate most of the Roy stories in the world of my father, [his] being involved with organized crime, and my mother being the model for clothes at the Merchandise Mart. That world is still very much real and alive to me, even though it’s not quite the same place.

Like the stories it’s based on, the film finds a lot of color and tension in the polarized nature of your parents, and the ways of life they pursued to get by.

I’m a first generation American. My dad came from Bukovina, which eventually became part of Romania and was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He didn’t come to the States till he was 10 or 11 years old—with his father, brother and sister—and established himself. I never, ever heard him or his father or brother speak German or anything like that. No gypsy dialect. Not Yiddish, because they were Jews. It was very odd. They were assimilated so quickly. There was a real dichotomy between my father’s family and my mother’s. I had these two sides and never had to reconcile one with the other. I enjoyed the fact that there was that difference and that distance. Also, my father was almost 20 years older than my mother. All that goes into the Roy stories.

The most recent book that I just finished is called “Ghost Years,” and it’s mostly, again, about Kitty, about the mother, her circle of friends, and her mother. In many of them, Roy is mentioned in passing. She was the parent I was closest to and spent the most time with. She lived to be 91. In real life, my mother. She had a troubled life. She had five husbands. I supported her for the last 35 years of her life. It was really a difficult time. What I wound up doing, as the stories have gone on, is examine the lives of women in that period. The suppression, the lack of opportunities, the dependency on men.

The film evokes that clearly.

I witnessed all this. It just stuck with me. I think it made me tougher. By the age of 11, I realized that I was responsible for myself. I couldn’t depend on anybody else. My father was dead. My mother was out of her mind and none of her boyfriends or husbands really wanted me around. I don’t blame them because I wasn’t the easiest child to handle. That’s just the way it went. I started working at the age of 11 and writing around the same time, and I’m still doing the same thing.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask for a David Lynch anecdote. As the Criterion Collection has recently issued a new 4K Blu-ray edition of Lost Highway, which made its theatrical rounds this summer, I thought I’d ask you about that collaboration.

I haven’t gone back to look at it in many years. The important thing about that is a story that’s been told a number of times by myself and David. He did Wild at Heart, of course. Then we did a television program for HBO called “Hotel Room,” which basically is only available on YouTube now. When Dave came to me, we had a couple of other ideas kicking around. He hadn’t made a film in four years. He said, “Barry, I want to make a movie and I want you to write it with me.” He had optioned my novel “Night People” and was trying to figure out how to make it into a movie. I said to him, “Listen, Dave, each of us is capable of half of an original thought. Let’s put our minds together and we’ll come up with something new.”

The title came out of something that one woman says to another: “You know, we’re just a couple Apaches, riding wild on the Lost Highway.” He loved this line, and it carried him to a place that intrigued him. That’s how Lost Highway came about. When the film came out, a lot of people were confused by it and didn’t quite understand what the story was. You know, how did this happen and how could people change [into another]? We knew what a psychogenic fugue was. It’s a mental condition. That’s basically what happens in that movie. It was just clear to us. And even if it wasn’t, if it was mysterious, in some ways startling, well… so much the better.

Barry, thank you so much and happy belated birthday.

Well, thank you. It’s really sweet that the film’s streaming as of my birthday. It’s a very nice touch.