By Gary M. Kramer

Guy Maddin’s distinctive brand of cinema is so gleefully imaginative that fans of this cult filmmaker can become drunk with giddiness watching his features and shorts. His style is one that is both experimental and expressionist, deftly using light and shadow, quirky editing, superimpositions, and asynchronous sound to create a mood piece that dazzles and delights. His films are witty genre send-ups that are full of absurdist moments and wild invention.

Keyhole (2011) is one of his most striking features. Taking its cue from Homer’s The Odyssey, Maddin’s film has Ulysses Pick (Jason Patric) returning home to find (and possibly forgive) his wife, Hyacinth (Isabella Rossellini), who is on the top floor. As Ulysses journeys from room to room, Keyhole becomes a road movie that never leaves home. What transpires is a series of episodes that involve memory—or the lack of it—as Ulysses tries, with the help of the blind Denny (Brooke Palsson) to recall his past. It is not for nothing that his father-in-law Calypso/Camille (Louis Negin), a ghost who is on the top floor with Hyacinth, often whispers, “Remember, Ulysses, remember.”

The film opens with a bunch of gangsters holing up in Ulysses’ house after a gunfight, and the film’s noir elements are rendered in the terrific use of chiaroscuro lighting. (The film is shot digitally, in luminous black and white with only two brief bursts into color). There is also some wonderfully hard-boiled dialogue. One gangster character, Big Ed (Daniel Enright), instructs, “All right, those of you who have been killed, stand facing the wall. Everybody who’s alive, face me,” which may have viewers scratching their heads until the characters do and it all makes sense within this surreal, microcosmic universe. When Ulysses utters, “This kind of weather stirs me up,” it is both flinty and deadpan.

One character only speaks in French (there are no subtitles), but Ulysses understands her. Denny has trouble remembering her thoughts and is on hand to read Ulysses’ memories. Manners (David Wontner), who is gagged and tied to a chair—he is a hostage—is Ulysses’s son, but Ulysses does not recognize him. Manners is dragged through the house while tied up (which could not have been easy) until he gets to take a bath, losing the chair and his clothes, but not the ropes or the gag. (Calypso/Camille is also chained and fully naked; but he is ghost who can moves through the house with more ease.) Maddin’s audacity and creativity is admirable.

The filmmaker layers the simple quest narrative with ghostly visions as if to pay homage to the haunted house/ghost story genre. The opening shot is of a face behind a curtain, and a repeated motif has Ogilbe (Kevin McDonald from the comedy troupe “Kids in the Hall” playing against type) dry humping a washerwoman ghost scrubbing the floor in a hallway. There is another ghost who screams from time to time, punctuating the action, and a terrific sight gag of Ulysses procuring three nails that a ghost holds in his mouth as he hammers away at a wall.

But there are also snippets of Ulysses’ late children, Bruce, who is caught playing Yahtzee in a closet—a metaphor for masturbation—his milk-drinking son, Ned (Darcy Fehr), and his daughter Lota (Tattiawna Jones) who is seen (in flashback) naked with Heatly (Theodoros Zegeye-Gebrehiwot), one of the gangsters. Heatly, it is revealed earlier, killed one of Ulysses’ sons, and was then adopted by Ulysses, who oddly came to love him more than his own children. (Such is the film’s roundabout logic). There is also an image of Ulysses’ wife, Hyacinth, as a young woman, running naked in a hallway with a dog.

Maddin is refreshingly blasé about the film’s copious nudity. There is even an amusing joke when Denny warns, “Cyclops ahead” as she, Ulysses, and Manners walk through a secret passageway where an erect penis protrudes from the wall.

Such is Maddin’s playful wit, which extends to his dizzying visuals. (The film is awash with surrealistic touches.) One of the most masterful sequences involve Manners’ science-fair invention, an electric chair that is powered by bicycles. When the device is first used, there are sparks and rapidly-edited images of ghosts and half-naked gun molls dancing while eerie music—it sounds like someone is playing the saw or a theremin—is heard on the soundtrack. There is smoke and a reverse/negative image to convey the “death” by electrocution. But then the device is used a second time, and the camera shakes, and there are more sparks, and the images are cut at such a fast clip that one might expect the film itself to catch fire.

Maddin also shows another one of Manners’ inventions, a “family desktop organizer” that sends messages through pneumatic tubes to family members. This sequence is almost completely superfluous, but it is so creative that it provides a nice comic breather for viewers.

Several scenes in the film are quite somber. One features Dr. Lemke (Udo Keir), who turns up in the house and recounts a sad story of losing his son. He later examines Denny, who is waterlogged and perhaps dead. Lemke’s grief adds the portrait of sorrow shared by Ulysses and Hyacinth, who are mourning their lost children. Various objects, such as a bowl Ulysses carries with him on his journey, are representative of the past and their late children.

Keyhole is all about memory and loss. A subplot about Belview (Claude Dorge) redecorating the house before dawn is echoed in a later scene where Ulysses, Hyacinth, and Manners try to restore a room in the house to “the way it used to be,” as if erasing the time of tragedy. (Clocks are featured prominently; in one scene, Ulysses moves the hands of a clock as if to literally turn back time.) This chaotic film becomes unexpectedly moving in its final moments as the characters reconcile past and present, hoping to assuage their guilt and embrace their memories.

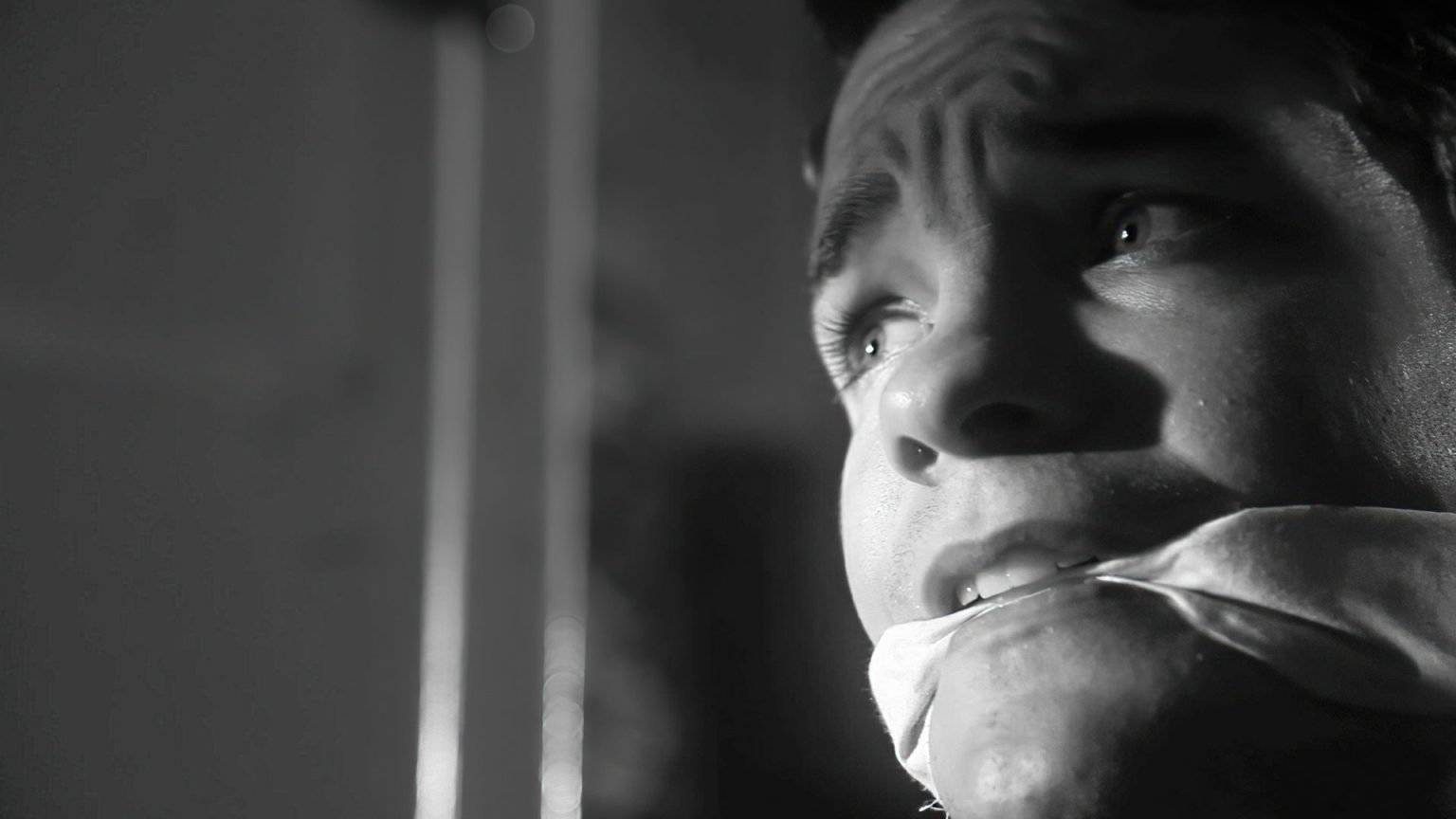

Maddin may not be known as an “actor’s director,” but he always casts his films well. Jason Patric, who may be best known for his smoldering turn in After Dark, My Sweet, gives a nimble performance here as a noir antihero, and Maddin’s camera loves his face, illuminating it in darkness, or capturing the sweat along his brow. Patric takes his role seriously, but he also gets a laugh when he quips, “That penis is getting dusty,” upon seeing the “cyclops.”

Isabella Rossellini and Louis Negin, who frequently appear in Maddin’s films, are attuned to his wavelength and deliver their lines in a dreamy way. Udo Keir provides reliable support in his scenes, and Brooke Palsson makes an auspicious feature debut as Denny. In what may be the trickiest role—given that he is bound and gagged through much of the film—David Wontner is impressively expressive and brings an intensity to his performance especially when Manners is able to speak.

Keyhole is certainly a film that rewards multiple viewings, as images and objects can take on greater meaning. Maddin’s achievement here is not just his fabulous world-building, but that his fabulist take on reframing The Odyssey along with cinematic genres is both unique and incredibly engaging.

© 2022 Gary M. Kramer

###

Keyhole (2011) from director Guy Maddin is now showing on Fandor.