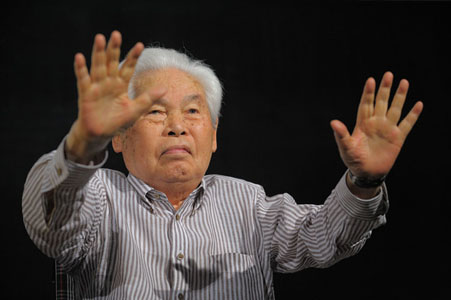

Renowned Japanese director and screenwriter Kaneto Shindo died of natural causes yesterday, reports Kevin Ouellette for Nippon Cinema. Born in Hiroshima in 1912, he “got his start in the world of film in 1934 when he joined the art department of Shinko Kinema and later studied under director Kenji Mizoguchi. After a stint with the Imperial Japanese Navy during the war, he moved to Shochiku and collaborated with director Kozaburo Yoshimura for several years. In 1950, both men left Shochiku to start their own film company, Kindai Eiga Kyokai.”

“He debuted as a director with The Story of a Beloved Wife in 1951,” reports the Mainichi. “His films won the Grand Prix at the Moscow international film festival three times with The Naked Island (Hadaka no shima) in 1961, Live Today, Die Tomorrow (Hadaka no jukyu-sai) in 1971, and Will to Live (Ikitai) in 1999…. Shindo directed 49 films in total, including the 1952 film Gembaku no ko (Children of Hiroshima), depicting the tragedy of the atomic bombing of his city. In all, 231 of his scripts were made into films, many of them winning awards at film festivals in Japan and abroad. His last film Ichimai no hagaki (A Postcard), won the Special Jury Prize at the Tokyo International Film Festival in 2010.”

Back in April, I posted a roundup in MUBI’s Notebook, “Kaneto Shindo @ 100,” and I’ll refer you again to Michael Atkinson‘s appreciation, written for Moving Image Source back in April 2011: “Shindo, never an exportable star nor an obedient studio soldier, has been a living model of prolificity, penning over 150 films in that period (often enough, a year would see seven films made from Shindo scripts, directed by the likes of Yasuzo Masumura and Kon Ichikawa), and directing 45, a no-nonsense cinema-is-life curriculum that hardly flagged as he went from conscientious postwar Ozu-ite to riled New Waver to contemplative Oliveira-like mandarin. The depth of his footprint on Japanese cinema is difficult to overestimate. If non-Nipponophile filmgoers have known Shindo in the US, it’s by way of Onibaba (1964), the bruising, hypnotic dog-eat-dog brother film to Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes (released the same year), and one of the most dire visions to emerge from the battery of hellspawn known as the Japanese New Wave.”

Update: “Many of his movies are allegories on the absence of civilized behavior in the conduct of war, exposing humankind’s innate propensity towards violence and cruelty in the absence of a moral and spiritual code,” writes Ronald Bergan in the Guardian. “Much of his humanism and style derived from the director Kenji Mizoguchi, for whom Shindo wrote two screenplays. In 1975 Shindo paid homage to his mentor in a documentary, Kenji Mizoguchi: The Life of a Film Director. Like Mizoguchi, Shindo created many forceful women characters who, by virtue of their willpower and love, tend to ‘save’ their male counterparts. In fact, one of his films was entitled Strong Women, Weak Men (1968). The female lead was invariably played by Nobuko Otowa, who became the married Shindo’s lover in the late 1940s. (They married in 1977 on the death of his first wife.) Otowa appeared in all but one of the 41 features Shindo directed from 1951 until her death in 1994. (This creative film partnership is surpassed only by Yasujiro Ozu’s 53 films made with Chishu Ryu.)… Among the events to mark his centenary is Two Masters of Japanese Cinema, a tribute to Shindo and [Kozaburo] Yoshimura, due to begin at the British Film Institute in London on 1 June 2012.”

Update, 5/31: Viewing (1’55”). Criterion presents “some silent Super 8 footage of the director on location during the filming of Onibaba, which was shot in Chiba Prefecture’s Inba Swamp in the summer of 1964.”

Updates, 6/1: In Sight & Sound, Alexander Jacoby notes that “a few months before Shindo turned 100, another centenary had passed almost unnoticed on the international scene. Yoshimura Kozaburo (1911-2000) was not only Shindo’s contemporary but also his close collaborator, yet he remains barely known in the West…. In their different ways, both Yoshimura and Shindo were to explore the social and political issues confronting Japan at a time of dramatic change, when the nation was obliged to take stock of its recent history. The trauma and tragedy of the Pacific War had particular relevance for Shindo. Conscripted as part of a unit of 100 men, he had been one of only six of these not to see active service; the other 94 were all killed.”

“When I finally had a chance to interview him at the Nikkatsu Studio in 2000,” recalls Mark Schilling in the Japan Times, “it was for Sanmon Yakusha (By Player), a docu-drama he was then shooting about Taiji Tonoyama, a hard-drinking, free-living character actor who had appeared in many of Shindo’s 45 films. Nothing austere about that subject—or Shindo’s sometimes blackly comic treatment of it.”

“Mr. Shindo’s body of work was known for its vast stylistic diversity,” writes Margalit Fox in the New York Times: “over six decades it ranged across social realism, horror, sex comedy and documentary. What unified his output was its obsessive quality; its concern with people—peasants, prostitutes, the poor—on the margins of society; the use of isolated, often claustrophobic spaces; the damaging interference of ghosts (of the psychological sort, though sometimes also the literal kind); and the presence of strong women. But for all their darkness, Mr. Shindo’s films were ultimately pervaded by an essential humanism, even hopefulness.”

Update, 6/2: “Despite being known outside Japan for only four or five films, their rich pictorial quality inspired a wide variety of graphic design in the 50s and 60s, especially from Czech, Polish and Russian designers.” In his new “Movie Poster of the Week” column in MUBI’s Notebook, Adrian Curry presents “my selection of the most striking work.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.