Gianfranco Rosi is an exquisite Italian documentarist whose 2013 film Sacro GRA was the first documentary ever to win the Venice Film Festival’s, Golden Lion. Winning this year’s Berlinale Golden Bear for Fire at Sea (Fuocoammare) made him the only director other than Michael Haneke to get top awards at the two most important European film festivals of the 21st Century. When handing Rosi the prize for Fire at Sea, Berlinale jury president Meryl Streep called the film “a daring hybrid of captured footage and deliberate storytelling that allows us to consider what documentary can do.” She also pointed out what many journalists stressed: It is one great piece of urgent, imaginative, and necessary filmmaking. Now also Italy’s official Academy Awards submission, Fire at Sea follows the everyday lives of a few chosen inhabitants of the small Italian island of Lampedusa. Once “La Isola Bella” and the desired tourist destination, the place has, over the last couple of years, become a goal for hundreds of thousands of migrants, traveling to Europe on boats from sub-Saharan Africa, Syria, or Palestine. The director has been traveling with his film ever since it opened in Berlin this February. We had a chance to discuss the film, and some other issues, during TIFF.

Anna Tatarska: You’ve basically toured the world with the film. It’s been eight months since it premiered at Berlinale in February, right?

Gianfranco Rosi: Almost… February, March, April… [Switches to Italian] Febbraio, Marzo, Aprile, Maggio, Giugno, Luglio, Agosto, Settembre…

Tatarska: Eight months, almost a full-term pregnancy!

Rosi: The worst period in the last three months, you know? At least for me.

Tatarska: And why is that so?

Rosi: Because I reached a moment… You see, when I am traveling with a film, I want to find the enthusiasm, keep up the good spirits and the good energy when I talk about it. But if you do too many interviews, then it becomes difficult to handle that emotionally. There’s a risk you may start repeating certain things over and over. And it’s painful. It’s like you’re frozen, everything inside you, emotion and things. It blocks your soul, you know, completely.

Tatarska: I can imagine. Having been to so many countries, do you actually see people reacting differently to the film based on their cultural background?

Rosi: Not really. I was in Austria, in Turkey, in Germany. In England it was huge because we were there during ‘Brexit.’ And it helped the film a lot. [Laughs.] But in general, no, not really. It’s just that in some places the film is more politicized than in others—for example in Europe like I mentioned.

Tatarska: What do you think is the basis for this universal appeal?

Rosi: There’s the island, with all its inhabitants, the migrants passing through this beacon of freedom that they try to reach. And then, outside the frame, there is also a third story: politics. Every place gets impregnated on this idea. I think the most political thing in my film is the title, Fire at Sea. The film itself is beyond politics. I mean, it might be politicized, but it’s not political, in the sense that there’s no statement in it. Everything’s quite open, although it’s a cry for help. It hopes to create awareness about the huge crisis that we’re all witnessing, we’re all part of.

Tatarska: This terrible context changes the way the film is perceived.

Rosi: If this film was coming out three years ago, exactly the same thing, it would never have this impact. So the impact is now up, because of the fear people feel when watching the film. The viewers are all like [my protagonist] little Samuele, coming-of-age souls, who still haven’t discovered the harshness of life and are afraid of the unknown arriving at them. Samuele, he’s afraid of life coming. Everything he does is somehow creating suspense for something we don’t know how to face, with our laziness and our anxiety: the world that is coming through Lampedusa. The subtext of the film is somehow reflecting on the viewer, I think. Subconsciously the viewer identifies with Samuele, but they are not able to say that they do. So, in the end, they’ll say it’s a film about migrants, but it’s not. It’s really on the coming of age of a little kid who lives on an island where everything reminds him about the sea. About the harshness of the sea, about the life on the sea, about becoming a fisherman, about suffering the seasickness. But the people are not aware of that. So in the end, they come out and all they remember is a film about migration. And it is so much more complex.

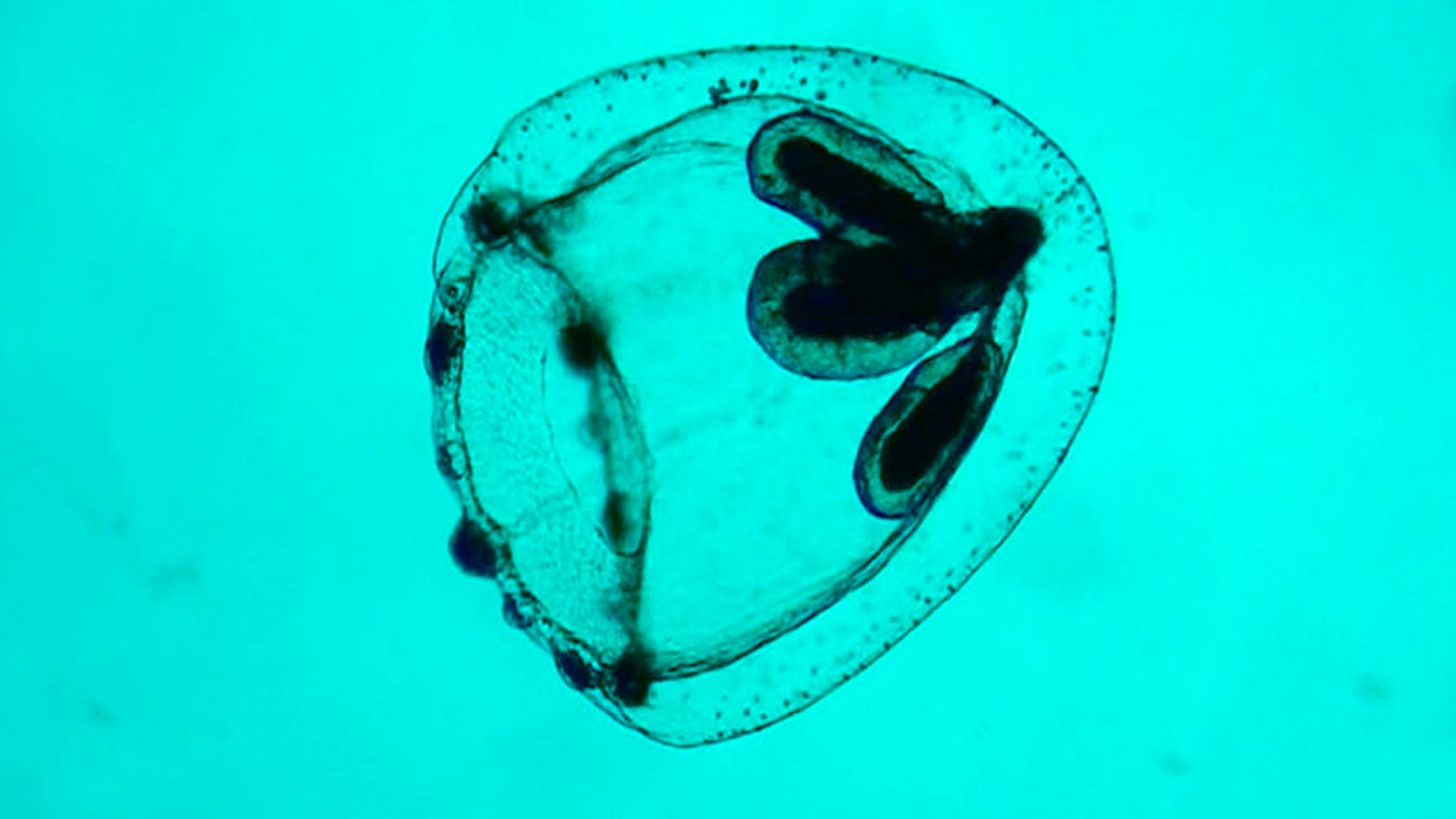

‘Fire at Sea’

Tatarska: We have already talked about Fire at Sea back in June. Back then you said you were not worried. I wonder about now, after experiencing the situation with those anti-immigration attitudes we had in Europe, in Poland, in Great Britain…

Rosi: …Austria, and so on. It’s soon France, Germany, and Italy probably…

Tatarska: You said you were not worried about States. You said I remember well, that you think Trump’s never gonna win.

Rosi: I still believe it’s not gonna happen because I still hope…

Tatarska: You’re Italian! Look at your politics, for God’s sake!

Rosi: I know, but… I mean, Berlusconi, we got rid of Berlusconi.

Tatarska: After how many years?

Rosi: Many, many. But somehow Berlusconi’s nothing compared to Trump, because the action of Berlusconi affects Italy only and the action of Trump would affect the whole world. And I don’t believe that people can be so blinded to vote for him. I refuse to believe that. I would not be able to work in the street or look at people anymore if that happened!

Tatarska: You’re describing how I feel about the political situation in Poland right now.

Rosi: Fucked-up souls.

Tatarska: You’re looking at your friends and thinking, ‘Which one of you fuckers has voted for this government?!’

Rosi: I have a friend in Turkey, he’s a very bright man, intellectualist, a distributor…

Tatarska: …Who voted for Erdogan?

Rosi: He’s loving Erdogan! He’s saying Erdogan is great because Erdogan has shown the power that Turkey was missing, not making it the ass of Europe anymore. I can’t believe that people can think he’s a great man. Seventy percent of Turkish people are in favor of him. Apparently, I don’t understand where the world is going anymore. But I still have the hope that it’s not gonna happen in America. I have an American passport. If this happens, I’m going to give up my citizenship, because it means I’m gonna be surrounded by people that are so far from what I believe in, I’ll have to run away.

Tatarska: So the political reality of the contemporary world makes you feel like you don’t understand it anymore?

Rosi: It makes me feel that if we keep going like this if we support this kind of politics, the world is going to experience a huge defeat. I’m so sure when I say that we cannot build a wall. Building a wall is something that history has proven wrong so many times. We are afraid and want to protect ourselves from something we don’t know, but doing it like that is gonna have horrible consequences in the future. When I say ‘in the future, it’s like in ten, fifteen years, you know? How can you stop three, four, five, six million people from moving?

Tatarska: How can you stop the world from changing?

Rosi: It’s always been like that, millions moving around the world, you know? [Laughs.] All the time. That’s how everything happened. And the fact that now we’re resisting it scares me so much. It’s like having a disease and putting antibiotics in the body up to the point when they don’t work anymore. So that’s what we’re doing: We’re pumping the elements that create darkness into our bloodstream. And at a certain point, they won’t hold anymore.

Tatarska: Films are a part of the culture, and culture should, in my opinion, be partly responsible for the ‘never again’ mission.

Rosi: If my film was to make two people say ‘what can I do?’ it’s already a big thing. It can create awareness. But I don’t think it can change things. I have proof it can’t because it was presented at the European Parliament, the Pope, the United Nations saw it…

Tatarska: And they were so moved.

Rosi: They were, yes. But then, after three days, the European Parliament was dealing with Erdogan and giving a billion dollars to him, to keep the immigration problem out of the way. Without even thinking that these three million Syrians there are treated like slaves there, with no rights, used for blackmailing Europe, to be exchanged for three million visas Erdogan wants to give to the Turkish. ‘I’m gonna send you three million Turks the next day if you’re not gonna do this and that!’ So we can’t accept this. I believe if every country—and when I say every country it’s not only Europe, it’s America, it’s Canada, it’s Asia, it’s Arabic countries—it ought to be a panel of the whole world in order to achieve some kind of agreement. That’s what they should do. Like an enormous panel with all the states of the world that would say how we can resolve this situation. ‘Cause, it is going to be explosive.

Tatarska: Big political issues overshadow the still ongoing, daily tragedy of the migrants.

Rosi: In Libya, we have around 250,000 people that are stuck there. They came through Sub-Saharan Africa from Syria, and can’t go back. The only thing that they can do is take a boat and become victims of the smugglers, and of rape. There’s also a pressing issue of human organ exchange. People are forced to sell their organs, their kidneys, in order to pay a hundred, a thousand dollars for the boat.

Tatarska: Paying for a trip that may ultimately lead them to death.

Rosi: We’re talking about protecting the border all the time. And we have to start moving our attention from the border and go in a different direction. For example, giving the people that are in Europe the possibility of moving around—creates welfare of that. When you have people moving around, they will naturally find their own position, find out where to go and what to do. You can’t just forbid these people that are in Europe to go back to their country, because otherwise, they would lose their papers. All these things breed anger. There’s just a need of understanding that identity is something that one has to give up in order to counter this. Each of us would have to learn that we have to give up something. It’s like in New York. In New York, you have to integrate. You give something of your culture, and someone else gives something from his culture and there’s a meeting ground, you know. That’s a perfect city that is a…

Tatarska: …A melting pot?

Rosi: It’s somehow an example of how different cultures are able to touch and interact with each other. That’s why I love New York. It’s a perfect city to live in. I’m always Italian, you’re always Polish, and each one gives up something of their identities. Like every artist has to give up something of his identity in order to absorb something else and create something new.

‘Fire at Sea’

Tatarska: Do your part with your files easily? What does the psychological, emotional transition from one project to another look like?

Rosi: I’ve spent one and a half years doing the film, I’m gonna spend one year talking about the film. This one requires a lot of talking. Now I’m starting to think about a new project. This one is still hard to let go of, to make the transition. I need like a moment of break. To spend one month with nothing happening in my life. Create an empty space inside of me.

Tatarska: Can you handle nothing happening?

Rosi: Nothing happening means I have to take care of myself. I don’t start a project unless I don’t find the truth inside of me, the vision inside, which has to be very, very intimate. And once you find that, you’re able to face a new project. I’ll tell you a story. When I was a kid studying at NYU I had the privilege to go visit the famous sculptress Louise Bourgeois’ New York studio. She showed me all her works. There was this incredible table in her loft, a very long one. It was full of objects and things of memories. She showed me this one piece of clay and told me how everything started from it. She kept it on her desk. This piece of clay was the beginning of everything. When she decided to become a sculptor, she didn’t know which shape give to her work, which direction to take. She only knew she had to find something inside of her, something so profound that everything afterward was going to be linked to that moment of truth.

Tatarska: Like a core?

Rosi: Like a core. And if you don’t have that, it’s impossible to visualize anything. She kept on going: ‘It took me days, weeks, maybe months, but I kept this piece of clay in my hands, every day. I was going to sleep with this piece of clay. I was shaping it, holding it, I was giving a form to it. I was embracing visions, images, and everything was passing from my hands through it. I was giving it a shape with my memories, my feelings. And one day then everything came clear and I left it there and it’s been with me for forty-six years.’ So you know, every project we do, we have to find that moment of truth, then create a new shape, a new world.

Tatarska: So in your case, it’s not just one piece of clay that’s the beginning of everything, but a different one for each project.

Rosi: Because for me every film is new. It’s the first and the last. That’s the beauty of documentary: experimenting. Without experimenting there’s no real documentary. You have so many types of documentary, so many different approaches. The reality’s constantly interacting with you. When I’m starting a film I have to be completely empty, discover it while I’m progressing. I discover things while I’m filming. I like to arrive at a place completely ‘virgin,’ with no ideas.

Tatarska: You learn hands-on?

Rosi: It’s better to learn on the site where you are. Before I start filming I have to go around, gather information, pieces of emotion. Everything has to be part of me. And then I have to find that clay inside of me. My way, that moment I have no doubt anymore. Once I find the people I want to be with, like on the island—Samuele, the doctor, the fishermen, Maria, and everybody—then they become a part of my family. I create a void. Nothing exists anymore, it just becomes an archetype of a place. As the place I want to tell the story about is reflected in the life of my protagonists, I hope to understand it through their stories. These people have this kind of emotion because they live in Lampedusa. You can make a film in the desert, in Mexico, in India, in Rome—it’s always the same. So I have to be able to find a space, first outside, and then inside of me, and then find the people that reflect my idea of the space through the story. It’s like a three-dimensional construction: the space, the people, myself. An exchange, a transformation of something. Of my idea, of their being, of the place itself.

Tatarska: How do you know you’re right about this feeling, that ‘this is it’? Is it just a gut feeling?

Rosi: You have to have that core. It’s not about right or wrong. It’s about true or false, which is different. My duty in documentaries is to be as true as possible to the life of the people that at that moment I’m telling the story about. No writer would be able to write the dialogue between the doctor and the kid. Or the scene with the bird, or the scene with the ultrasound, or the scene of Maria doing the bed, or the scene of Maria giving coffee… Everything comes [to me] in an unexpected moment and that’s the transformation of reality beyond my imagination.

Tatarska: It’s like with Dr. Bartolo—if you wrote a character like him, who would say things he says, nobody would believe it.

Rosi: If I wrote it, it would be cheesy. But he does exist. Finding the truth in a documentary is fantastic, the truth of the people. And once they’re there, they become an archetype. From Tibet to China, to Greece, to Toronto, to New York—there’s a universal language that these people from this little island know. I asked Dr. Bartolo what made this island so special, that for twenty years 500,000 people passed through it and he, they, always accepted the newcomers, never complained. ‘What makes this place so generous?’ I wanted to know. And he said, ‘We’re people of the sea, we’re fishermen, and fishermen always embrace anything that comes from the sea.’ I believe we, the people of the land, have to learn to be like these fishermen and embrace everything that comes from the sea, or elsewhere, including the unknown.

BAMcinématek hosts a Gianfranco Rosi retrospective from October 28 to November 3, with Fire at Sea showing on Sunday, October 30 at 6 p.m.