Man of Marble offers one of the most spectacular stories of a movie battling against the odds to pass censorship and see the light of day. A related article offers director Andrzej Wajda’s account of what it took over a 15 year period to develop the project and get the script past state censorship. But even once the film was in the can, there was a long battle to get it to the Polish audiences to whom the film is dedicated.

Matilda Mroz sets up the social context for this struggle in her “Great Directors” account of the government’s plan to quietly supress the film upon its initial release:

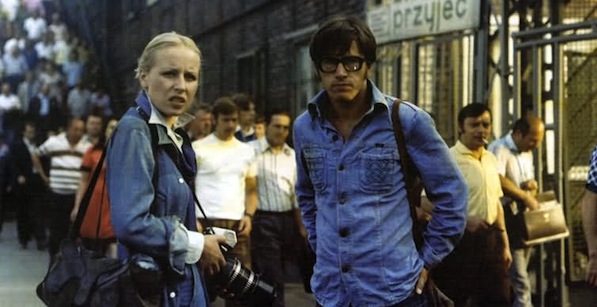

The opening night was set for February 25, 1977; at first – at the insistence of the authorities – only a handful of prints were prepared. They expected that if ‘Man of Marble’ would not be allowed any publicity, and all reviews – as ordered by Premier Piotr Jaroszewicz – would be negative, the film would not catch the public attention and the problem would be hushed. But things turned out to be quite different. (…) The famous scene during the Gdańsk Festival – Wajda receiving a brick bound up with a ribbon – became a manifestation of unity of the whole community, filmmakers and critics.

Wajda’s website posts a variety of reviews that convey the film’s reception both domestically and abroad. First, Wiktor Woroszylski, writing in “Wiez” May-June, 1977, reports about how Warsaw audiences were able to see the film despite the government’s attempts to suppress it:

First, I tried to get into a screening at the “Wars” cinema, without success. On Friday night, someone called me, very excited, and said that the film was to be screened at three other cinemas. In the morning, the door-bell rang – it was a neighbour with whom I exchanged good mornings in the forecourt. She said: “By the box-office at the ‘Wisla’ movie theatre some nice young men are compiling a list of those who want to see the film. Hurry up.” I was sixtieth in this strange community of people who wanted to see Man of Marble, and who wanted it more passionately than the usual film-fans. (…)

I recognised my own generation with its black-and-white faith (just like on the screen), enthusiasm and naivete, with its, not yet anticipated, susceptibility to later disillusionment and defeat; I had been there, I had unloaded bricks at night at the Nowa Huta railway siding, worked my way through mud, slept in a big hall with the members of the young men’s work brigade, written about them a poem as primitive as they were, and read it aloud in the light of a weak electric bulb. (…) I am recollecting all this not because I feel sentimental about our youth; I think about it – in life and on film – with mixed feelings, which involve sentiment but also painful self-irony, shame, bitterness… So, is this a renaissance of Polish film? Perhaps not only of film?*

* The censors deleted the two last sentences before publication.

As the film gradually made its way outside Poland, European critics, including some within the Communist Bloc, embraced it:

I have found in this film a piece of splendid journalism. It communicates so much that an army of Western correspondents would not be able to gather this information. My belief that didactics and aesthetics in film should be separated of has been shattered. This is an experience so rare in today’s cinema that this film should be spared any critical remarks.

– Franz Manola, “Die Presse”, Vienna, 20 September, 1980

Wajda’s synthesis has given birth to an outstanding art work about revolt against submission. Historical limitations are recognised, but people don’t have to wear masks or have double standards any longer. Passionate and driven by the desire for a harmonious life, Man of Marble is an exceptional drama about the revolt of flesh, blood and common sense in defence of the right to authenticity, naturalness, and spontaneity. This is not nihilism – to the contrary, it is life – lived with the awareness that such a way of living is the most free, and the most moral.

– Sveta Lukic, “Borba”, Belgrade, 24 February, 1979

The beauty of this exceptional film lies in the complexity of the director’s attitude towards Birkut, a representative – perfect in his submissiveness – of the whole miserable, alienated period. Wajda wants to communicate two opposing truths: first, that stalinism was a disaster and second, that the people who believed in it – and whom it consequently crushed – were driven by an honest spirit of idealism. It hasn’t been easy to juxtapose these two messages, but Wajda has succeeded completely. Like every artist worth his name, he began not with the typical, but with the individual. (…) What was the effect of this delicate operation? Stalinism has been unconditionally condemned, but socialism as an idea and utopia seems to be saved.

– Alberto Moravia, “L’Espresso”, Rome, 29 April, 1979

However, things were not all well back in Poland, if one can infer from the following report by Krzysztof Klopotowski in “Literatura”, Warsaw, 23 October, 1980:

Even though two and a half million people have already viewed the film, Andrzej Wajda’s name has been covered with mud. This has been the biggest press campaign in the last decade directed against an individual artist, a campaign that became a test of courage and decency. The attitude towards this campaign clearly divided critics, journalists, and activists, while decent people were found in unexpected places. Especially so, as defending the film was almost an act of heroism and some people lost their jobs in the result. So when journalists presented their award to Wajda at the Gdansk Film Festival in 1977, the censors office banned all mention of the fact and the honorary brick could only be awarded to the prize-winner on the stairs of the festival building. (…)

Andrzej Wajda had carefully balanced historical and moral arguments. At one end of the scale he put human fate, at the other – material progress, but he didn’t say which side “weighed” more. He presented a certain story but left room for different evaluations. It was precisely this objective attitude that caused such a furious outcry. This witch-hunt directed against an artist revealed the fear of the hunters. They did not want a public debate about the origins of their power, because they were afraid of losing it. They were leading the country to disaster and three years later they lost their power in disgrace, thus indirectly proving Wajda had been right.