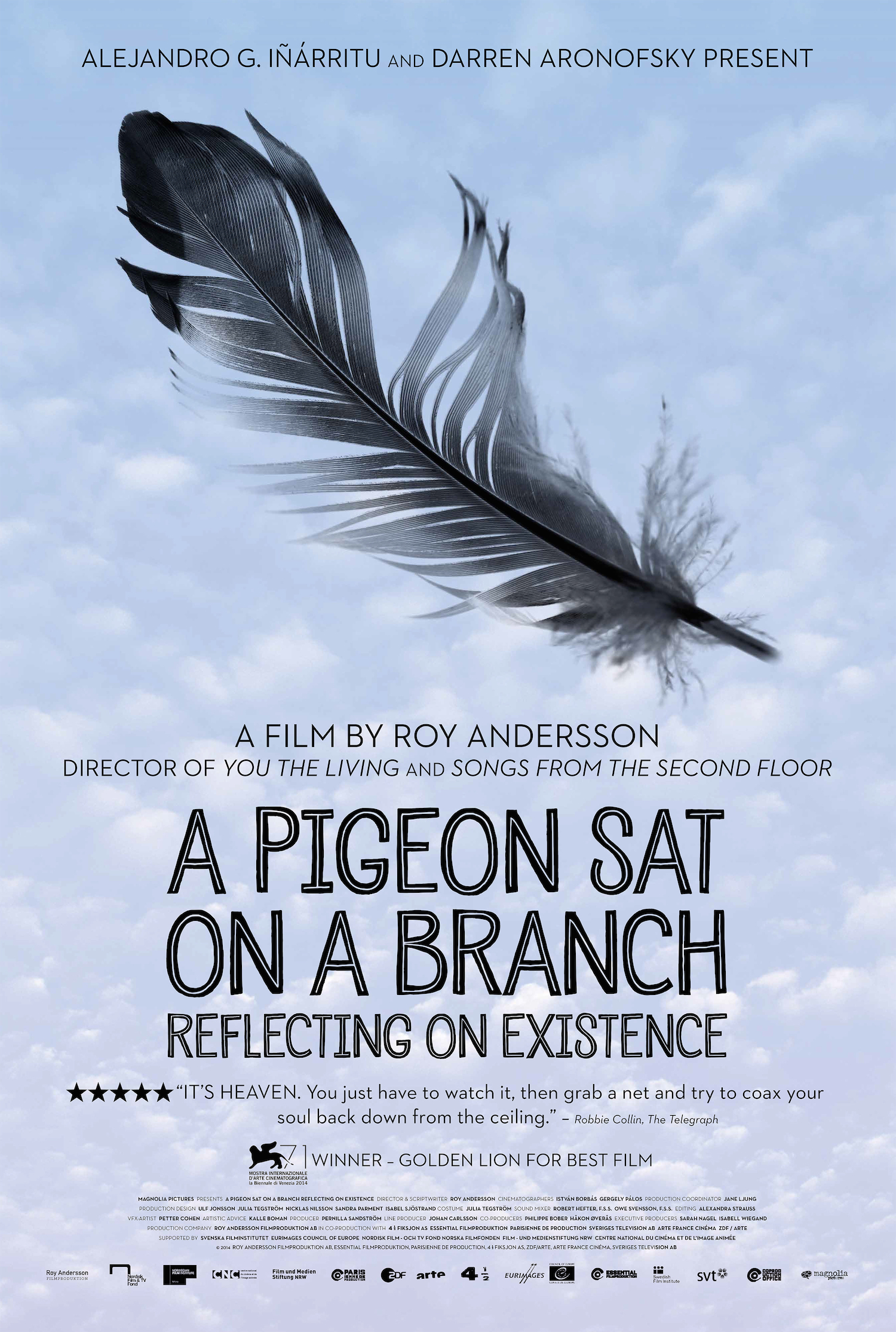

The magnificence of the affable Swedish director Roy Andersson is borne of decades. In 1970 the director’s full-length feature A Swedish Love Story was very well-received though his current creations of fantastic worlds grew out of an abandonment of that film’s realism. His long short film, World of Glory, gave us some of the perspectives that would come to dominate his worldview, which solidified in the creation of the first part of his four-film trilogy Songs from the Second Floor, a compendium of forty-six scenes that took almost four years to produce. He and his crew will work for a month to build a set and the shooting will take as little as one day before the set is dismantled and the new one built. Sharing the Cannes Jury Prize for that film, Andersson embarked on the miracle of You, the Living, then spent the next several years on his Venice Gold Lion–winning film A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, now rolling out across the States. The whole spectrum of being human erupts from the prism of Roy Andersson’s mind and those of fellow creators.

Shade Rupe: After seeing your latest film I’m looking out the window here thinking, ‘Is what we’re seeing here even real? Is that a backdrop? Did somebody build this just for our interview?’ The exterior backgrounds that you have in your film, the things that we see outside windows, do you construct everything we’re seeing?

Andersson: Everything. Yeah.

Rupe: Even when they dump the laughing bags out on the street, all of that is a construction?

Andersson: Yeah. Yes.

Rupe: Do you ever use the photographic process where you take a picture of some buildings and blow the image up really large onto translucent material and put it outside the set and light it from behind, or are you building small models for each background?

Andersson: We make small models. I prefer to work in three dimensions. That’s what we make all the time. When you talk about that scene when they stand by the train tracks and the laughing masks are tossed in the street, this is a combination of elements. The train is a model, it’s a small train, so we have combined that model into the full-size set.

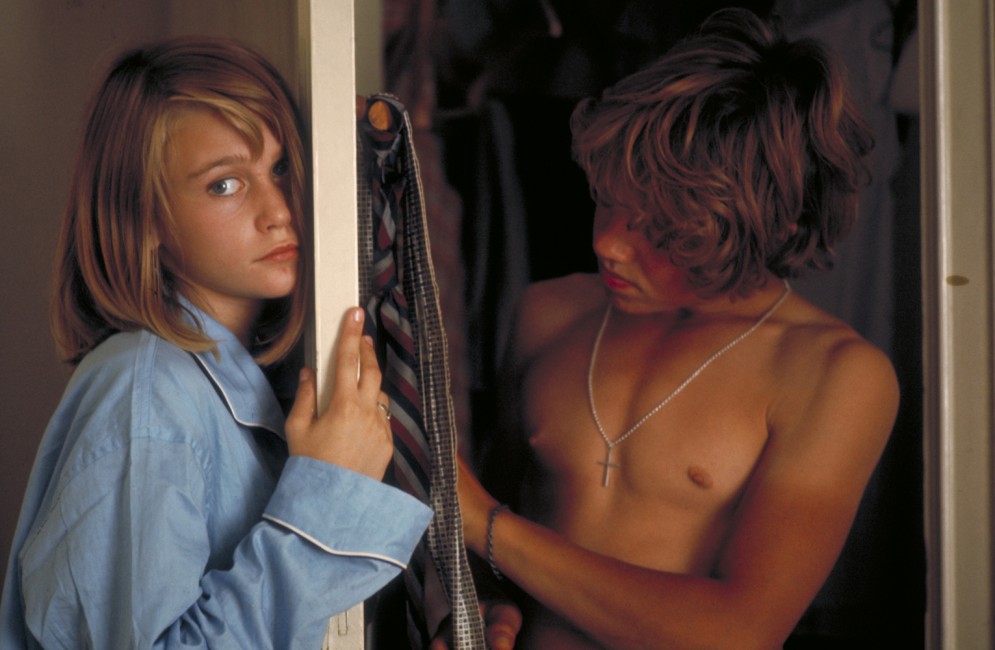

Rupe: Swedish Love Story is such a different approach. That film has the camera moving around, capturing much more action in a real-life environment.

Andersson: More normal.

Rupe: I’ve read that you’re finding video much easier to use to get a sharper, deeper image, though it’s popular for people to just wave the video camera around. They’re using it just to quickly gather up pieces of story or action.

Andersson: Right.

Rupe: The way video records information tends to flatten the visual field, but because you’re working and creating with these highly defined perspectives in your film, you’re allowing video to have a depth that usually isn’t utilized.

When did you begin to have that visual idea that you wanted to work in these perspectives, with hallways, and jutting corners?

Andersson: Step for step, I found that I really needed deep focus for what I want to achieve. I can’t make the background scenery clearly visible without deep focus. Diffuse background for me is terrible, but I started in that style with Swedish Love Story. But now I’m inspired by painting history. In painting history, you have almost no diffusion in background. It’s deep focus all the time. During the realist periods and even later.

I am a big fan of some German painters from the thirties. Many of them. There was a period called ‘Die Neue Sachlichkeit.’ That’s translates to English as, ‘The New Objectivity.’ There you have deep focus all the time. Sometimes the human beings are grotesque, but, however, background is always sharp.

Rupe: While watching Pigeon last night I thought of the work of George Tooker. He worked in perspectives and his characters have these worried faces, unable to relate to the world around them. Even though people populate his images, they are in little isolated boxes inside the world of people. You can really feel this in the flophouse, where the salesmen live, in the open door in the hallway to their room.

Andersson: To be honest, I’m not sure I know him.

Rupe: [….shows a Tooker subway image to Roy] See the depth and perspective, and the worried looks on the faces?

Andersson: Beautiful. That is fine. He’s good.

Rupe: He was an American artist and who just passed away a few years ago, in 2011. You can even see here how he gives depth, space, and pulls out bits of humanity inside. How separate each of these people are inside of a social world.

Andersson: Fantastic!

Rupe: You can see why he very much makes me think of your work. His work has been referred to as Magic Realism.

Andersson: I must say I’m very grateful that I belong to this. Yeah. Magic Realism.

Rupe: Did you know you were always going to be working in a filmic way with your environments? Have you ever considered creating an installation?

Andersson: Yes. I made an exhibition together with some other artists. One was about the Holocaust. I even made sculptures. We’ve had at least two exhibitions about the Holocaust. One was called ‘Sweden and the Holocaust.’ I used a very special method because they are full-size. I actually made them by three-dimensional scanning and using a 3-D printer.

Rupe: Are you familiar with Edward Kienholz’s work?

Andersson: Oh yeah. The State Hospital, the one with the two figures on the bunk beds with the fishbowlheads is in Stockholm at the Moderna Museet.

Rupe: Do any of your film sets stay built or they all destroyed after the end of shooting?

Andersson: Destroyed.

Rupe: Have any museums offered to keep any of your set pieces on display?

Andersson: No. In A Pigeon Sat on a Branch, there are thirty-nine sets and all of them were destroyed. They are full size, so you can’t save them. We had no space for that. I can save some details of the set but I’m happy that we have at least shot what we built. Sometimes I really regret that we have destroyed some of them.

Rupe: And the drum at the end? Was that a digital effect or did you build this giant drum?

Andersson: We built it.

Rupe: Was that actual fire under the drum or that was digital?

Andersson: No, no actual fire because that drum is made of wood. Plywood painted bronze.

Rupe: The men probably had another door to leave out of before you turned the drum.

Andersson: They had an opening on the back side. Yes, of course.

Rupe: In You, the Living, the character pulls the tablecloth off the table, revealing two swastikas. In art exhibitions that you’ve worked on, you concentrated on the Holocaust, and in your short film World of Glory we see a gas van in operation.

Andersson: The Holocaust is something that has haunted me all my life. How people can behave the way they did during the Nazi time and even nowadays, in colonialism. I was born in 1943, that’s when Nazi Germany was at its worst. It was the top of the gassing period. I’ve always felt something… some guilt about it. I was not involved, of course, but I feel guilt because I think of the human beings who were murdered.

In some way, I feel involved in it. That follows me still, but I was a little relieved when I’ve met a philosopher. His name was Martin Buber, a moral philosopher, a German man with a Jewish background. He wrote about guilt and feeling of guilt because he said when you commit a crime against existence, it can also be collective. You will feel guilt against existence. How can you live further with that? Can you get rid of it? Yes, he felt. You can repair that crime, not necessarily in the time when it was committed or at that place. You can repair it in another time and another place by being good yourself. Very optimistic philosophy.

Rupe: You’ve mentioned it before, but with the texting, with the people walking around. Staring at a screen, they’re not seeing a person.

We recently had an explosion in the East Village. A whole building blew up here. Tourists went there and took photos of themselves with their cameras in front of the explosion site, where people had just died.

Andersson: It’s a bad sign. I hope that the attitude to that will change. I think it will be boring for the coming generations to be transfixed to the mobile cellphone.

Rupe: Do you see this in Sweden also? Do you see young people doing this?

Andersson: Yeah. They are sitting longer. Trams, in the metro, and the buses. People sitting and tap tap tapping away all day long.

Rupe: You somewhat address this disconnect in A Pigeon Sat on a Branch where the people will call each other on the phone and go, Yes, I’m fine. I’m happy to hear from you. There is a disconnect in picking up the phone with what’s actually being felt and what’s being transmitted. There is definitely a push to create constant distraction, and exchange actual experience for distraction.

Andersson: Yeah. It was so nice to hear from this journalist a few days ago, right before we left Sweden. She saw the film in a screening room with only two rows and she sat in the second row. She was so intent on the film she really didn’t want to miss a millimeter of the screen, so when the person in front of her moved, she also had to move, just to see the picture. That’s very encouraging to hear that you have made something that can create that much interest in a viewer.

Rupe: Do you feel that any of your work can be translated to a live theatrical experience? I know there would be a lot of sets, though there they do have rotating floors available.

Andersson: Yeah, that interest is coming up for me. I can see the quality that living theater has, a ‘something else’ that movies do not.

Rupe: Because then you’ve got an actual human being that you connect with.

Andersson: I’ve tried actually. I’ve tried to direct theater. There was so little time for rehearsal, so it was not that good… It was good sometimes, but it was very … For me, it was stressing to see that, one day, the first act was very good and the second, very bad. We tried to change it, so they could both be good. The next day, that one was bad and the second was good. Very hard!

Rupe: Your designs are so full and so intricate. You’re creating these fully realized environments. Since you’re so interested in life and so interested in some of these fantastic ideas why do you choose to have a washed-out yellowish, greenish background, with very low contrast? Why choose a minimal pallet to create your stories rather than bright, shiny environments?

Andersson: What I search for and try to get, is that sense of timelessness, even geographically my films are not specified, but first of all timelessness. For me, my timelessness is coming up from my memories from the time I grew up in Gothenburg. It was the period when the welfare state was being built up in Sweden. They built so many houses for people to have flats and so on.

The architecture and the color from that period, in the fifties, have such strong memories for me, so that’s my timelessness. Timelessness. I really want to be timeless. Like cartoons, purified and condensed. I’ve been accused many times of repeating myself with these ugly colors, but I can’t leave it. No.

Rupe: Here in New York, the buildings that we remember and grow up loving, and identify ourselves with, are taken from us and we get very bland buildings in their places. Is that happening in Stockholm also?

Andersson: Yeah. Now, they are planning terrible things in Stockholm. There was a fantastic period in the thirties. Now, they are destroying historical architecture from the thirties, but there are lot of protests against it. I hope they will not succeed. I’ve also engaged in the protest actions.

Rupe: The thinking isn’t, ‘Oh, but if we do this, 500,000 people will a home.’ They just put people in bland housing, and charge them more money.

Andersson: In Sweden, the politicians, they are so afraid of costs. They always talk about reduced costs. The spiraling effect of that can be very bad finally. As long as I have the power to protest, I will do it.

Rupe: Although you’ve earned money creating hundreds of commercials, I’ve read you were not creating commercials during the production of this film. Will you be returning to any commercial work before production or will you be going right into it?

Andersson: No, because now that field has been so bad. The businessmen have taken over, the artistic people are gone.

Rupe: Did you raise all of the money for this film yourself or did you have outside agencies participating?

Andersson: I have good contact with the foundations, both in Sweden and in Europe. Eurimas and the television station CanalArte. It’s a collaboration between France and Germany and the Swedish Film Institute.

Rupe: Have you already begun production on your next film? I’ve read it will be the fourth film in your trilogy.

Andersson: Yeah. We have started pre-production. My next film is based on the 1001 Nights and will be called About the Eternal. Or something close. I want it to be endless. About endlessness.