In 1982, documentarian Peter Davis (Hearts and Minds) produced an expansive series of films for PBS. The “Middletown” Project was based on Robert and Helen Lynd’s groundbreaking micro-sociological studies of Muncie, Indiana, conducted in the 1910s and ’20s. Davis and PBS commissioned a total of six films, each engaging with a different social institution (politics, religion, business, marriage, sports and education) from a distinctly micro-sociological point of view. That is, the films explore the ways that individuals or small groups navigate these cultural formations, making personal or group decisions from which broader social conclusions may be drawn.

Taken as a whole, the Middletown films function a lot like a cinematic inverse to Michael Apted’s “Up” series. The films provide a deep core sample of suburban Midwestern existence in the early 1980s, the project’s reach scattered as it is across many distinct populations and demographics. For example, the series implicitly asks to compare Family Business (dir. Tom Cohen), which profiles a retired Marine colonel and his family as they struggle to maintain an underperforming Shakey’s Pizza franchise, with Community of Praise (dir. Richard Leacock and Marisa Silver), a portrait of another family and their involvement with a fundamentalist Christian ministry. What we see is the hangover of the late 1970s (Ford-era inflation, the collapse of social liberalism and post-New Deal Keynesian consensus) and the consolidation of Reaganite hegemony.

As it happens, the Middletown project also provides an exceptional object lesson regarding the institutional imperatives of PBS, sociological documentary and the nonfiction film form more generally. Seventeen, by Jeff Kreines and Joel DeMott, is the only film from the project, historically speaking, to have attained breakout notoriety. It won the Grand Jury Prize for Documentary at Sundance in 1985, and subsequently played at numerous film festivals where it garnered a great deal of critical praise. However, if you read that last sentence and noticed a discrepancy —a 1985 award for a 1982 film—you’re beginning to understand the particular problems that Kreines and DeMott’s film presented for the “Middletown” project.

PBS declined to air Seventeen. Although the Corporation for Public Broadcasting has never explained its decision, er, publicly, Kreines and DeMott have claimed that the network bowed to pressure from Xerox, the series’ corporate underwriter (PBS-ese for “sponsor”). But the filmmakers also argue that producer Davis helped sandbag Seventeen from the series, or at was at the very least derelict in his duty to fight for their work. The film, therefore, was effectively unseen for three years, and largely out of circulation until now.

With the benefit of thirty years’ hindsight, what can we make of Seventeen, and its position within the “Middletown” series and the resulting brouhaha? That Kreines and DeMott’s documentary found favor with artists while it ran afoul of bureaucrats is not so surprising; this happens all the time. But what was it that Seventeen tried to tell viewers (about Muncie, the early ’80s, about documentary form) that certain authorities preferred be left unsaid?

At its core, Seventeen is a look at a group of students at Muncie’s Southside High, observed from basketball season to the prom. Starting with the extended opening scenes, one continual refrain in the film is a rather haphazard Home Ec class that serves as a sort of makeshift home base for the intersecting cliques who will serve as Seventeen’s primary subjects. As the grizzled instructor tells them they aren’t making pie crusts correctly, she takes getting cussed out in stride. She also gently counsels a pregnant student and the baby’s father about their impending responsibilities, matter-of-factly and without judgment. This is particularly notable given that she is an elderly white woman, the two students African American.

How exactly did Seventeen transgress PBS’ canons of bourgeois good taste? There is ample underage drinking, drug use and discussion of sexual hook-ups among the lower-class Muncie teens. If you were a conservative Xerox executive whose only concern was corporate image in charitable giving, pulling the plug on Seventeen would be an obvious pre-lunch decision. (This film is a clear influence on both Larry Clark and Harmony Korine, but with twice the humanist sorrow.) PBS, never known for its courage when tasked, would buckle under in due course. But one might justifiably ask, where was Peter Davis? This is a question pertaining to a complexity that Seventeen both exposes and helps to create, one to which the other “Middletown” films simply don’t match up. This is almost certainly by design.

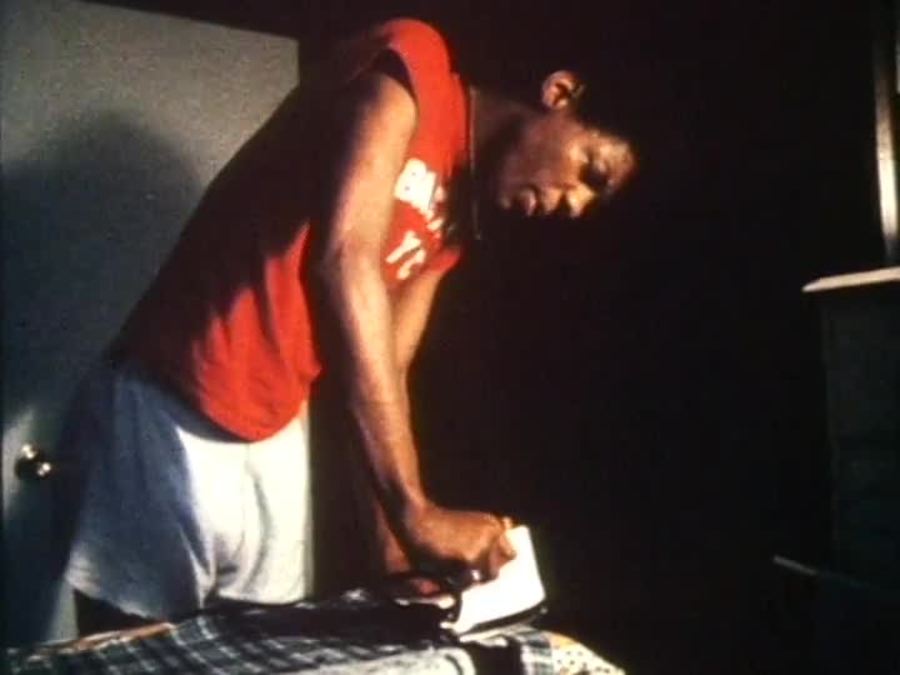

Seventeen is a racially charged film, but in highly complex ways. Kreines and DeMott discover a roiling but ultimately banal racial optic in underprivileged Muncie, one that ultimately conditions every social interaction. At the start of the film, one of the featured subjects, a white girl named Lynn, has gotten involved with a black student named John. This results in uncomfortable intermixing between John’s (black) male friends and Lynn’s (white) girlfriend, as well as anxiety about Lynn’s parents finding out. We see the guys at Lynn’s house with her parents around, and they are fine with their daughter being friends with black kids; being romantically involved, however, would be another matter. (The young white guys in Lynn’s orbit are uniformly racist, casually or virulently depending on the situation.)

What Kreines and DeMott observe is troubling in unexpected ways. Racism in 1982 Indiana is flexible. That is, when Lynn tries to explain her social crises to John, she refers to being with him as “swallowing [her] pride,” claiming that for him, dating a white girl would be a step up, but for her she is losing status and “no white guy will ever touch me after this.” Likewise, when John withdraws his interest, Lynn reverts immediately to racist in-speech and groupthink, dropping the N-word and preparing for racially-defined gang violence.

Seventeen is not, then, a clean and decisive portrait of a failing educational system, or a group of young girls facing the challenges of impending adulthood, although it contains elements of these ideas. If we compare Kreines and DeMott’s style and approach with, say, that of Peter Davis himself, who co-directed the “Middletown” entry on divorce and remarriage, Second Time Around (co-dir. John Lindley), the expansive, unruly cinematics of Seventeen are thrown into stark relief. Second Time Around begins with an establishing shot, followed by a well-lit, static introductory interview of its male subject, followed by a parallel introduction of its female subject. Its formal parameters follow from there.

Seventeen is often handheld, underlit, grainy and characterized by harsh, fleeting patches of color. These visual modes contrast with the brown and beige, evenly lit spaces (school, suburban homes) that try and fail to define Lynn, John and the others. Above all, Kreines and DeMott shoot and edit with a sense that the subjects at hand are expanding in unexpected and often vertiginous directions, lurching and hurtling without a defined sense of self.

Instead of treating the “Middletown” project as an examination of a known property or a Durkheimian “social fact” (work, marriage, etc.), the filmmakers take their title quite literally. “Seventeen” is the age just before legal adulthood, the end of mandatory schooling and entry into what for most of these kids will be dead-end lives of broken promises. Kreines and DeMott capture them at a final moment of uncertainty and experimentation. What is perhaps most heartbreaking is that this unformed possibility includes a spark of racial inclusivity, and entry into “Middletown” almost immediately snuffs that out.

[Editor’s note: Peter Davis follows up on this story for Keyframe in “SEVENTEEN: Peter Davis Responds.”]