A movie cannot, alas, stop a war. But every now and then one tries, and the effort can be stirring, infuriating, majestic. However many films might qualify for this subcategory of cinema-vs.-life textual combat, it’s arguable that Far from Vietnam (1967) was the most lavish, passionate cataract of anti-war intervention ever put on film. Emile de Antonio’s politically-focused In the Year of the Pig (1968), as pedagogic as it was, paled by comparison as activism, while Peter Davis’ Hearts and Minds (1974) didn’t appear until it was already far too late. Far from Vietnam took no prisoners, because it represented not one filmmaker’s point of view but a community’s, indeed, an entire polyglot generation’s, and so of course it was derided and attacked during its timely release and became unattainable in any form but bootlegs for nearly half a century.

It’s a messy, polyphonous, conscientiously disruptive film, conceived and assembled by our greatest political cine-essayist, Chris Marker, from segments contributed by a murderers’ row of New Wave royalty: Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais, Claude Lelouch, Agnes Varda, Paris-based fashion photog-turned-filmmaker William Klein, plus a soldier from the old Loyalist left, sixty-seven-year-old Dutch documentarian Joris Ivens. Joined by an army of sympathetic technicians, actors and producers, the filmmakers endeavored to construct the equivalent of a pissed-off cinephilic peace march—a brand new idea. Far from Vietnam was, in fact, the first documentary created in direct resistance to the U.S. invasion of Vietnam, which makes it the first nonfiction film ever made anywhere protesting a war while the war was happening. Fiercely expressing international, but particularly French, opprobrium toward American policy and actions, the movie was at least a few years ahead of its time.

When it was shown in the U.S., first in the 1967 New York Film Festival, sensibilities were offended and fresh scabs were ripped off; Richard Roud, writing for The Guardian reported anti-Red catcalls of “Moscow gold!” at the screening, an anti-Communist insult-code referring to the Spanish Civil War-initiated financial support for Communist organizations everywhere but Moscow. In the New York Times, infamous grouch Bosley Crowther complained that the movie was “frantic and formless,” lambasting it for its outrage (it’s certainly not fair and balanced, the oddest of all accusations leveled at documentaries) and for using “scurrilous” agitprop juxtapositions and inflammatory rhetoric. Of course, to inflame was the film’s purpose. Why didn’t it succeed?

In the fall of 1967, “radical” was still far from the American mainstream, however close France was to the insurgent fever that famously took hold in May 1968. (That year, de Antonio’s doc was protested and threatened wherever it found theatrical release.) But in 1967, the shock for us of the Tet Offensive lay several months ahead, and the news of My Lai wouldn’t break for another year and a half. Woodstock was still almost two years away, and the shootings at Kent State were almost three. This was why college campus protests, once they began in earnest, were alarming news to most Americans—the notion of mass collective action in open defiance of the government’s actions was not something that had happened in America before. Workers’ strikes had always been focused on specific industrial entities or areas, but now it was huge swathes of us, our kids and neighbors, gathering by the thousands, facing rifles and screaming for change.

Far from Vietnam captures this screaming better than any film did (as well as the blindly patriotic, vitriolic hollering in response). Released by New Yorker Films in June 1968 for only a single week and in a truncated cut thirty minutes shorter, the film found almost no traction even among critics for leftist publications like The Village Voice—Andrew Sarris proclaimed the film “zero as art” and slammed it for fuzzy thinking (one mustn’t idealize Asian peasants, one should be sure to paint their dark side, even as they are being bombed) and what he saw as unintended ironies (full-throated American protestors and their jingoistic opposites were seen as equally grating, as though the filmmakers didn’t try hard enough to make one side less so). Stanley Kauffmann, easily the laziest thinker among long-standing, seriously-considered magazine film critics in this country, dismissed the movie in The New Republic as “blithe about hard political issues,” suggesting in five words only that Kauffmann had no working familiarity with the film or with the meaning of the word “blithe,” or whatever was “hard” about the politics of the war.

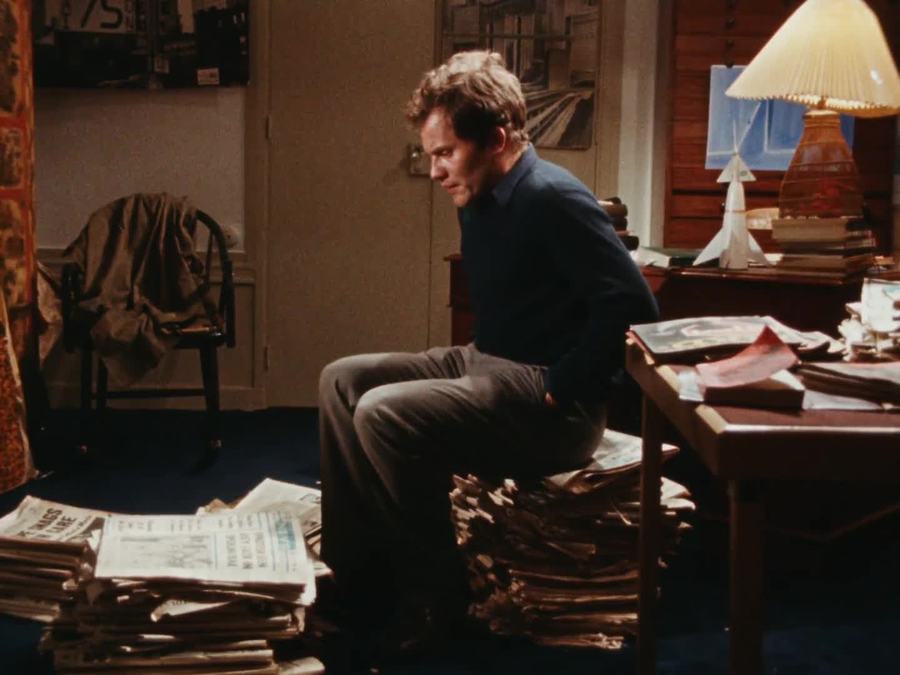

Look at it today: it is neither fuzzy-minded nor romantic nor unaware of its ironies. It is in fact a furious, full-throated lament. The various segments, which are never attributed to individuals, are deliberately eclectic in voice, agenda and form, mixing stock footage, first-hand documentary scenes, pop-media imagery, philosophical arguments, and, in the case of Mr. Resnais’ segment, scripted actors (Bernard Fresson, veteran of Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour, The War Is Over and Je t’aime je t’aime, stars as a noodle-spined French intellectual monologuing on the excuses for his class’s political apathy).

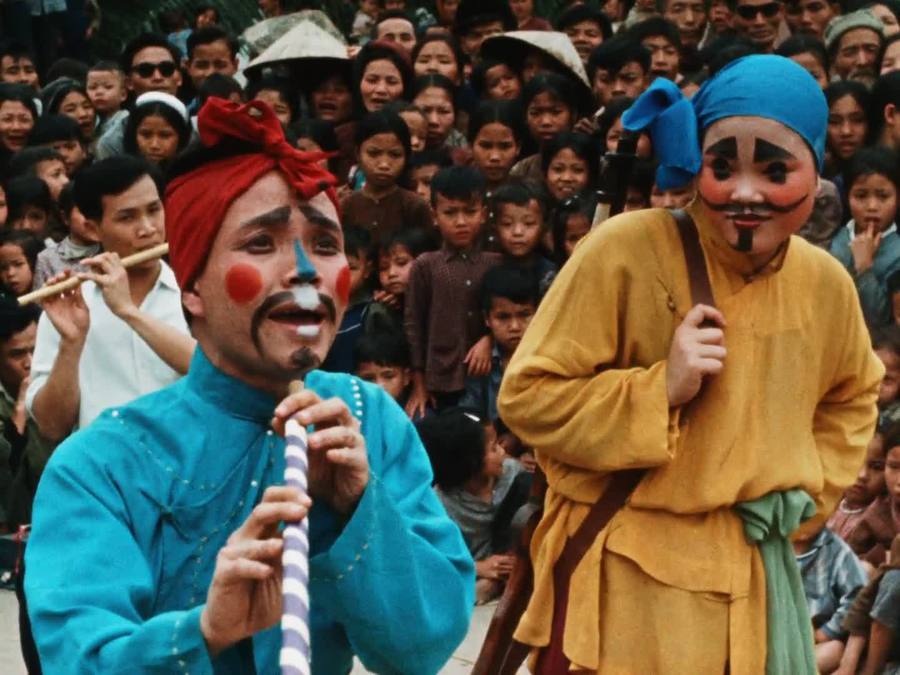

The mix includes unintentionally self-roasting speeches from Hubert Humphrey and General William Westmoreland (so much for unintended ironies), folk satirist Tom Paxton singing “Lyndon Johnson Told the Nation,” a detailed stock-footage history of post-colonial Vietnam, a “traditional” North Vietnamese clown play about President Johnson weeping over his air force’s failure, aforementioned visits with vein-popping American protests at home, new interviews with Ho Chi-Minh and Fidel Castro, portraits of Hanoi inhabitants as they manufacture and then employ one-man cement bomb shelters, and so on.

It could’ve been a weekly TV show, revealing to us one after another the infinite ways to attack the war, and to assess its damage. Typically, Godard’s segment rises above the others in terms of the deep thinking at its core. Unable to go to Hanoi, he muses on the soundtrack about his conflicted relationship with sociopolitical injustice, while visually exploring a 35mm camera, bemoaning the very inadequacy, in the face of wholesale genocide, of filming anything. His hesitant solution, for us all, is to “instead, let them invade us”—that is, figuratively, to resist imperialism wherever we are, “Africa or Chicago or Rhodiaceta,” the latter the site of a massive workers’ strike in Besancon that Chris Marker would make two films about in 1968.

The omnibus’s death strike, however, comes with Mr. Klein’s segment about the legacy and surviving family of Norman Morrison, a thirty-one-year-old Baltimore Quaker who in 1965 doused himself with kerosene outside Robert McNamara’s office window at the Pentagon and set himself ablaze. How exactly this hair-raising bit of all-American history did not become common knowledge decades later—the self-immolations of Buddhist monks in French Indochina are more familiar to us—remains a vexing question. Was Morrison’s suicide even permitted by the media to have survived in the public consciousness by 1967? (For some it did—a vigil for Morrison was held in front of the Pentagon in May of 1967, six months before Far from Vietnam.) Klein in any case also makes clear that for the Vietnamese, Morrison became an instant and unforgotten folk hero, redubbed Mo Ri Xon. Homing in on Morrison’s serene pacifist widow, who never wavers from endorsing her husband’s martyrdom, Klein raises the stakes beyond suffering, and into the inescapable bind of moral imperatives.

With its tender righteousness clearer than ever today, Far from Vietnam remains, finally, a fact of history itself. It’s not a matter of what the film’s “about,” but what it ineluctably is: an act of resistance in cinematic form, a brickbat thrown at the powerful. Part of its legacy now naturally involves how ignored the film was, how effective it wasn’t allowed to be. An old strike-hand, Marker defined his mission as battling atomization, fostering “solidarity,” but the real enemy is complacency. “We are far from Vietnam,” he ruefully concludes. Toward the anthology film’s end, an unseen American commentator observes that “American morale”—meaning, American apathy—about foreign wars could only be changed by native “bombardment,” “some damage to a city on our shores.” Of the many moments in Far from Vietnam that resonate beyond the immediate circumstances of the war in question, this one cuts your blood, because we’ve seen, in 2001, the stone-cold reality of what he was imagining. We’ve also seen, sadly, that our “morale,” our capacity for privileged apathy and even ethnophobic malevolence did not diminish on 9/11. On the contrary—our comfort with and appetite for imperialist crime seems only to have flourished.