It was fully expected in many quarters that the Beatles would be “over” by the time their feature film debut hit screens in 1964. Never mind that Beatlemania (originally the film’s title) had been bigger than any pop-music phenomenon since Elvis. The “Fab Four’s” appeal, seemingly inexplicable to anyone over fifteen (especially males), was surely just another fad, one that would exhaust itself faster than a pubescent’s attention span. United Artists had entered into the Beatles business only to exploit a loophole in their recording contract, which did not encompass movie music. So the studio figured it could make a small fortune releasing the film’s original soundtrack, one that would offset any losses should the film itself flop.

Nevertheless, they weren’t taking any chances with what was eventually called (after a catchphrase of Ringo’s) A Hard Day’s Night. Nearly all the creative decisions that seemed genius in retrospect were arrived at for one reason: They made an inexpensive project even cheaper.

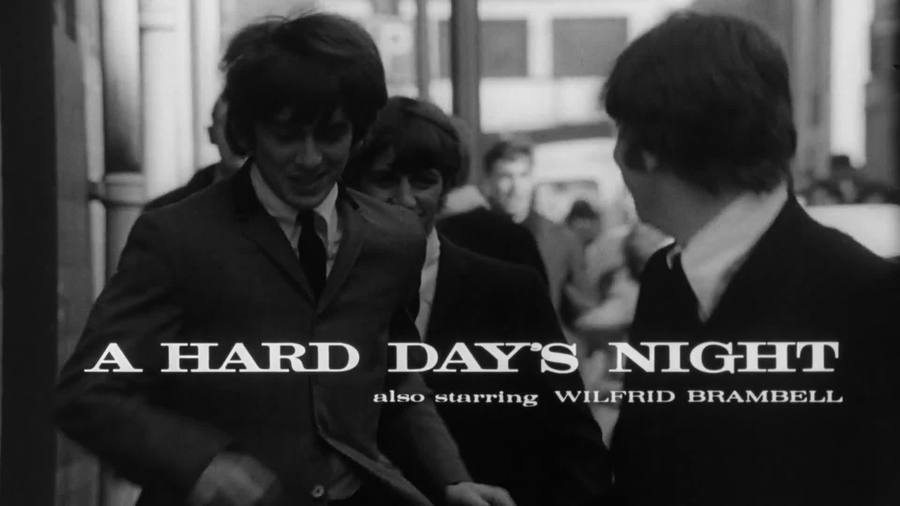

Thus it was decided that the film would break from the cheesy plot conventions of such prior rock movies as Rock Around the Clock and Hey, Let’s Twist! by being a “fictional documentary” depicting an imaginary “typical” day in the four madly popular Liverpudlians’ life together. That rendered acceptable shooting on-the-fly in black-and-white, mostly in real locations (not studio sets), often with actual fans playing the screaming hordes who chase the “boys” everywhere they go, including in the film’s memorably chaotic opening sequence. (One such extra was Pattie Boyd, who met George Harrison here and married him two years later.) Roles for professional actors were mostly fleeting, more like extended cameos. The major exception was casting Wilfrid Brambell as Paul McCartney’s alleged grandfather, an alternately prudish, childish and anarchic figure who’s the center of numerous gags. While his name meant little to international fans, Brambell was box-office insurance in the U.K.: He was enormously popular as star of the sitcom Steptoe and Son (which was later “Americanized” as Redd Foxx’s 1970s hit show Sanford and Son), the oft-repeated line “He’s a clean old man” being an in-joke reference to that broadcast series.

Costing less than 200,000 pounds (about a half-million U.S. dollars at the time), A Hard Day’s Night was the first major big-screen assignment for Richard Lester, a Philadelphia native who’d emigrated to the U.K. in 1950 and would still erroneously be considered an “English director” decades later. He’d already done numerous TV shows as well as a more traditional film vehicle for rock/jazz acts (1962’s It’s Trad, Dad!) and a more standard comedy (1963’s The Mouse on the Moon).

But what caught the Beatles’ eye was The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film, an eleven-minute 1959 short that starred Goon Show regulars (including Peter Sellers) in a series of antic, plotless sight gags notable for their everyday absurdism. (It would be most directly echoed in what became Night’s signature sequence, where the four stars frolic in an open field to “Can’t Buy Me Love.”) Lester’s playful sensibility, low-budget resourcefulness and high-energy camera/editing innovations became hugely influential, on everything from blatantly imitative American series The Monkees (which “Prefab Four” fake-band sitcom launched two years later) to the MTV culture that wouldn’t fully bloom for another two decades. Indeed, with its numerous wacky, pranksome sequences that simply accompany soundtracked songs sans any pretense of live performance, A Hard Day’s Night often feels like a strung-together series of early music videos.

While it may have seemed just that thrown-together to United Artists brass, the movie was very cannily aware of its audience’s age and tastes. They were acknowledged in everything from a stray glimpse of Mad Magazine to the pervasive, mocking suspicion directed toward “grownup” authority figures. As their day of tiresome obligations with press, management and others wends toward a climactic TV-studio performance, the Beatles are forever trying to escape the boring squares telling them what to do. This being the early , they’re not yet calling for “Revolution”…seemingly all they really want is to run free and play like children. (Despite the occasional blink-or-miss-it nod toward adult sexual desire.) Their cheekiness invariably ruffles the feathers of the uncomprehending, like a fashion maven (Kenneth Haigh, a respected stage actor who thought it best to go unbilled while “slumming” in this “slumming” teenybopper movie) whose commercially crass pretensions George casually reduces to dust. Constantly assaulted by fuss, criticism and public demands, the unaffected, working-class Beatles remain above it all…in the end, literally so, as a helicopter lifts them to their next engagement, scattering autographed 8 1/2 x 10’s Earthward in its wake.

Created with such low expectations, A Hard Day’s Night proved a global sensation, making about twenty times its production cost in original release, then another few million when returned to theaters in 2000. It was even nominated for two Oscars (Best Screenplay and Adapted Score). Today, the film’s lighter-than-air jauntiness makes 1964’s other “big deal” big-screen entertainments (My Fair Lady, Goldfinger, even Mary Poppins) look as cumbersome as military tanks next to a pogo stick.

No doubt the Beatles could have continued making movies, if they’d wanted to. But they didn’t, at least not the kinds of frivolous vehicles aimed at teens that had slowly eroded Elvis’ music and credibility, those churned-out programmers just as brainless as their titles (Kissin’ Cousins, Harum Scarum, Clambake, Tickle Me, Girl Happy, Girls! Girls! Girls…) suggested. If Elvis remained too much the simple country boy to resist the direction he’d been steered in, the Beatles rapidly grew too savvy to fall into any such trap. They preferred using the medium for more ambitious purposes commensurate with their stature as (very soon) elder statements to a burgeoning youth culture that was pushing the boundaries on every artistic and sociopolitical front.

But there would be no more Hard Day’s Nights. Not from the Beatles, at least. (In the British Invasion feeding frenzy, other bands would try to fill their cinematic shoes: Herman’s Hermits starred in two innocuous features, and the Dave Clark Five in Having a Wild Weekend, a rather trenchant sendup of youth culture marketing itself that was the first feature for future Deliverance and Excalibur director John Boorman.) The Fab Four and Lester did let themselves get rushed into a followup, 1965’s spy spoof Help!, which was in color, three times as expensive, shot in various “exotic” locations and about as successful (but no more so). They did not particularly enjoy working on a bigger, more conventional film.

Lester then went off to an erratic career in mainstream features (including The Three Musketeers and Superman II), while the Beatles focused on their ever-more-sophisticated music, as well as (reluctantly) being “spokesmen for a generation.” Before breaking up, their remaining film ventures consisted of the poorly received TV special Magical Mystery Tour, over which they had complete control; the animated Yellow Submarine, to which they only lent songs (actors mimicked their speaking voices); and 1970 documentary Let It Be, which wound up being a sort of group swan song.

Pulled into the avant-garde by his new love, John Lennon became much involved as a collaborator on Yoko Ono’s experimental films. George Harrison eventually became a prolific film producer, his company Handmade Films producing some of the most adventuresome British features (including Time Bandits, Withnail & I and Mona Lisa) of the 1980s. When all four Beatles embarked on solo musical careers, Paul McCartney continued to produce and occasionally direct films that were mostly concert showcases for his band Wings. Eternal class clown Ringo embarked on a comic acting career—and he’s still at it, most recently lending a voice contribution to a Powder Puff Girls movie spinoff. There are only two Beatles still alive now, but A Hard Day’s Night remains forever young.