As much as his second and third films deal with classifications, diagrams and at least mentions of attempted order, Peter Strickland began and remains an unclassifiable filmmaker. With three feature films, all highly regarded and immediately noticeable as the work of a well-honed mind, Strickland’s latest creation of picture, sound, motion and feeling is being received with open arms–and minds. Maybe occurring somewhere between the open mountains and fields of Transylvania seen in his remarkable debut Katalin Varga and the confines of the sentient cognition of the recording machines of his enigmatic Berberian Sound Studio, though more likely occupying its own place in its own realm, The Duke of Burgundy finds Strickland’s omnispheric senses picking up not only the delicious buzzing of Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa, the European mole cricket, though the inner measures of two women in love, and the pain that almost all couples can face in their relationships, outside the realms of genitalia and scholarly interests.

Though Katalina Varga’s eponymous lead Hilda Péter immediately grabs us by our necks and drags us through into the fire of her own internal hell, in Burgundy Strickland is assisted in creating his multi-textured characters with the playful Chiara D’Anna, returning from a smaller role in Berberian, to the matronly grace of the divine Sidse Babett Knudsen, and their lovely lounging about in a sumptuously ramshackle mansion deep in the solitudes of Hungary, replete with an all-female cast that finds solace in the nocturnal symphony of butterflies and moths, telling stories to each other of caterpillars, which result in orgasmic response. Peter Strickland’s The Duke of Burgundy is a ticket to transformation for those ready to spread their wings.

Shade Rupe: How much exposure had you had personally to the type of relationship in The Duke of Burgundy?

Peter Strickland: In terms of film stuff, definitely, yeah. That was around me a lot—with filmmakers I’ve worked with; the Cinema of Transgression; having worked on Bruce LaBruce’s Skin Flick. Certainly, the first person who introduced me to the whole film world in New York was MM Serra at the Film-maker’s Co-op. The films she made with Maria Beatty, A Lot of Fun for the Evil One, with John Zorn’s sound effects and music, were totally in this world. Again, the films Maria Beatty made as well, like The Black Glove.

I tried not to worry too much about being accurate. It is an artificial world they’re in. It was more about the whole dynamics of it, the fact that one person has these needs to be commanded, but, of course, on her terms. Then, one clearly would prefer this kind of vanilla relationship. I’m not going to judge either person. How does this work when they have very different ways of expressing themselves in sexual terms?

Rupe: Even though you’re an admitted lover of exploitation films, the way that you chose to characterize the two women in your film was really much more accurate than exploitative.

Strickland: Exploitation cinema had already covered the masturbation part of The Duke of Burgundy. They are inside the fantasy. They are not reality, which is fine. If I had made a film of Evelyn’s thoughts when she’s charging off, basically, it would have been that kind of film: exploitation film.

All I’m doing is stepping outside of that fantasy and showing the mechanics of it. Once the orgasm has happened, that ice-queen persona kind of rubs off. She has to go to bed eventually and put on her pajamas. She’s not going to sleep in a corset. She gives the impression that she sleeps in a corset and high heels when she’s sort of walking back and forth across the room. Evelyn’s inside the box and doesn’t know that Cynthia is wearing her pajama bottoms to feel more comfortable.

Really, in my head, it’s kind of ping-ponging between the ideal, if one has those desires, and the reality. I think the reality, not only for couples, where one person is doing it to please the other who’s not actually into it. Those couples who have this harmony are very happy indulging in role-play. There comes a point where you can’t do it all the time.

I hadn’t really seen that in cinema. I hadn’t seen that, ‘Right, I don’t want to wear a corset tonight.’ Or, the action, ‘Tonight, I missed my cue. I was supposed to punish this person, but I missed my cue.’ Or that fear of, this relationship is a loving, mature very, very trusting relationship. Being in that kind of relationship, it puts them in a box. The first question you’re going to ask is, ‘Can you breathe?’ Obviously, the person in the box isn’t going to want to hear that. They want to be commanded. But obviously you don’t want to kill your partner. It’s putting your head in that kind of perspective.

The other thing I find in cinema is the whole theatricality of it. It’s a great platform to explore the power dynamics in any relationship, but more importantly, it is the power dynamic that I have as a film director when I work. One relationship with acting, the fear that can have on a persona, a fear of getting your lines wrong. This idea of Evelyn’s scripts, seems a kind of parallel, a shadow of my script. Evelyn’s tape marks on the floor, being parallel to my tape marks. Evelyn is directing Cynthia. If there’s a film, say it, but I have yet to see a film where the submissive was calling the shots.

Rupe: The Night Porter.

Strickland: Ah, okay, of course, I have seen The Night Porter, yeah, of course. Yeah, but it wasn’t—

Rupe: Yeah, sure, but you see, you’re one of the very, very few that actually chose to see the relationship for what it is. I’m certain you’ve seen Maîtresse with Bulle Ogier.

Strickland: I have seen Maîtresse, yes. That’s probably the closest one. I mean, that’s who she was, and obviously, Depardieu is not remotely interested. It’s an activity quite exotic for him. That’s true, I think he pulled Ogier out of character as well.

Rupe: You’re talking about script, and how Evelyn’s scripting. The words are what keeps Cynthia going. Evelyn’s words, her script, is part of their loving relationship. Another woman writes the script for even a few moments in one afternoon. That’s enough to be betrayal, a hurtful event for Cynthia.

Strickland: That flirty boot polishing is kind of the same as someone being caught in a flirty email at work. The only difference is, that, as you mentioned, being commanded has such profound sexual power for Evelyn. It’s as good as sex for someone else. I think it’s the same level of pleasure for her by just being told to polish someone else’s boots. What I find really interesting is when Cynthia is commanding Evelyn to rub her back for her, it is absolutely heaven sent she would be used like that. When Cynthia pleads to have her back rubbed when she’s in her pajamas, Evelyn will do it, but it’s not remotely exciting for her. It’s not about the action, it’s not about the back rub. It’s not about being pissed on. It’s the whole dynamic that surrounds it that makes it exciting.

Rupe: You have Monica Swinn in your film, who was also in Jess Franco’s Female Vampire a.k.a. The Bare-Breasted Countess. There is a scene in that film where Lina is on the bed, nude, opening and closing her legs, and the camera just sits there on her crotch. There’s a somewhat similar scene in The Duke of Burgundy where Cynthia sits alone on a couch and the camera slowly moves into her very very low-lit crotch. Was that a visual reference to Jess’ film?

Strickland: Maybe in hindsight it was, but that was not intentional. There are things that were intentional sometimes, I mean some of the camera jibs were copied. I think the way Franco used bevels, I think certain lighting that we used for the dark panels, that was copied from A Virgin Among the Living Dead.

I think the way his characters look into the camera, we took that image in The Duke of Burgundy. I think, usually the character looks a little bit at the camera, it feels as we’re being taken outside the film at times. It’s brash and insensitive. I sort of do it, it’s still looking at the camera and still being completely within the film, and just have a sense of touch and smell. I know Franco used that in Lorna the Exorcist.

Rupe: Were Sisde and Chiara involved in the creation of the characters at a script level at all, or were they primarily taking the script and interpreting those characters on set?

Strickland: The latter. Sisde came in quite late and I was re-writing it at the last minute. They broke to the words, but saying that, they brought so much to the characters that I couldn’t do on paper, especially Sisde with her expressions, that great sense of frustration that she has. Small little tics, you know, when Sisde flicks Chiara’s nipple, that was spontaneous. I had no idea she was going to do that. It’s in the body language and facial expressions. That’s them, that’s them.

Rupe: How many takes did you do of Chiara responding with, ‘Really?’ after the Carpenter mentions the possibility of the couple acquiring a human toilet? She looks so gleeful.

Strickland: Not that many, actually. I’ll tell you why. We had so much fun in the bedroom with the bed and measuring that. That’s when we discovered that the mirror’s there. We really didn’t think about it before, but Nic Knowland messed around with these bevels. We just went to town and had a lot of fun with it. We just kind of whizzed through that top of the scene, but not that many takes.

Fatma is an actress I trust immensely. I’ve worked with her in all three films. She always transforms herself every time I work with her. Again, I don’t want to judge what Evelyn needs, but it’s beautifully sad when Cynthia looks through the window and sees Fatma’s gestures. I played Claudio Gizzi’s Flesh for Frankenstein for Sisde on set when she looked through the window to set that mood.

I think it’s hard when you do these things. Obviously, my job as a director is to make my characters annoying, make them misbehave, tease them, put them through stuff. At the same time I want to give them some kind of dignity. They are human beings who love and have feelings. They’re not freaks.

I think by the Carpenter being so indiscreet, and saying, ‘Oh, the neighbor bought a bondage bed,’ and implying there is a demand, shows they’re not freaks.

Rupe: There’s a normalcy, a popularity of behavior. This may even well extend into the community.

Strickland: Absolutely. I wanted to normalize the whole thing. Again, I think through cinema, it seems a bit of an exotic curiosity. I think there are levels of it in every relationship. Some are extremely marred and suppressed without even knowing, perhaps. Then, you have the very, very deep-set example. I think The Duke of Burgundy is pretty mild. It’s a very tender relationship. If you want the hard-core stuff, S&M, there’s Fassbinder’s Martha, which is really a different kind of way of expressing one’s needs for subservience.

Rupe: Had you considered other ways to present the water sport scenarios in the film? When I view Pasolini’s Saló, I’m not disgusted. I think they were very tastefully done, actually, in that film especially compared to what comes later. Had you considered other ways of expressing that part of their relationship besides the closed door?

Strickland: Not really. I’ve seen it done and look, Almodóvar’s first film, Pepi, Luci, Bom. It’s fantastic. It’s my favorite water sports scene in cinema. I think when he gets up on the table and just pisses in the mouth of someone, it’s great.

To me, it would be stepping outside the film. The film has to have this elegance. What I wanted to do was make a film where would dress it up in this opulent, elegant manner. I think what’s real interesting now, in the UK it’s an 18 certificate. There’s no nudity, and no swearing, no blood. It shows it can be quite powerful, you don’t have to show it. You can still jolt people. I’ve been watching with an audience, and I had one women in front of me, just really jolted when that water sports scene happened.

Rupe: How early did the title, The Duke of Burgundy, come to your film?

Strickland: Not that early. When the script starting changing, the gender of the characters changed; the first draft had men as well. Once it was all women, it was as much of a thing that, I am a man making a film with all these women, so, let’s have one concession to this male presence. I’m not sure that it says that I am as a Duke, so—

Rupe: It’s a beautiful title. It’s very elegant. I’ve researched that particular insect, and I don’t see any direct correlation at all. Burgundy gives a sensation of velvet, almost. It’s a grand title.

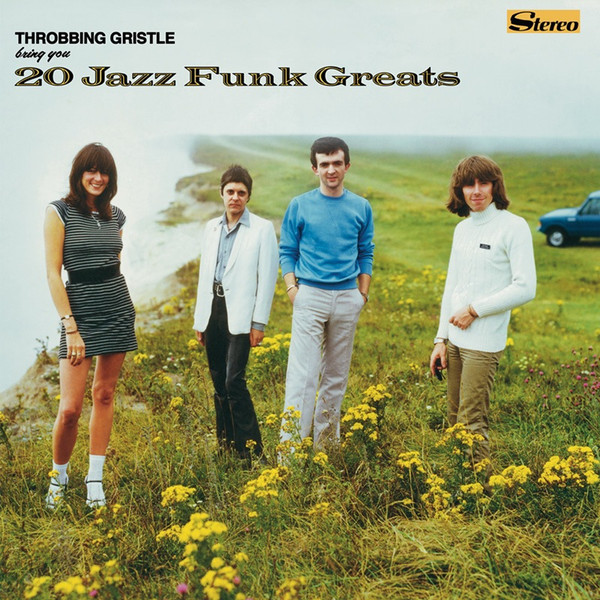

Strickland: No, it’s a title that, obviously, the insect is in the film, but it’s a title I enjoy. It sets an atmosphere that you think it’s kind of tasteful period film. It is misleading, which I like. I love that Throbbing Gristle title 20 Jazz Funk Greats, when it sounds nothing like jazz funk.

I think if you mislead someone out of perversion, I think it’s fine. If you mislead them to sell more copies of your film or whatever, I don’t like that. To me, this is more enjoyable, perverse, misleading.