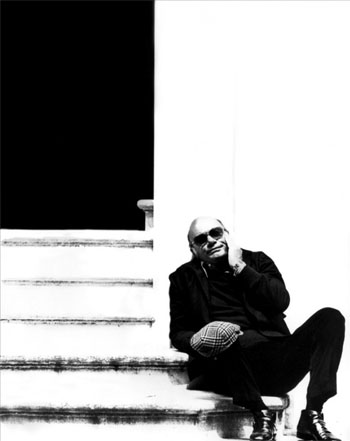

Several Italian papers are reporting that Francesco Rosi has passed away at the age of 92. In 2003, Gino Moliterno wrote for Senses of Cinema that Rosi practiced “an intensely-charged, politically-engaged and socially-committed cinema which has quite justly earned him the title of Italy’s cinematic ‘poet of civic courage.'”

“The films of Francesco Rosi stand as an urgent riposte to any proposal of aesthetic puritanism as a sine qua non of engaged filmmaking,” writes Verina Glaessner for Film Reference. “From Salvatore Giuliano [1961] to Illustrious Corpses [1976] and Chronicle of a Death Foretold [1988], he uses a mobilization of the aesthetic potential of the cinema not to decorate his tales of corruption, complicity, and death, but to illuminate and interrogate the reverberations these events cause. If one quality were to be isolated as especially distinctive and characteristic it would have to be the sense of intellectual passion, of direction propelled by an impassioned sense of inquiry. This can be true in a quite literal way in Salvatore Giuliano, in which any ‘suspense’ accruing to Giuliano’s death is put aside in favor of a search for another kind of knowledge; and The Mattei Affair [1972], in which the soundtrack amasses evidence which is presented virtually in opposition to the images before us; or, in a more metaphoric sense, Christ Stopped at Eboli [1979], which represents an inquiry into the social conditions of the South of Italy.”

“With Salvatore Giuliano, Francesco Rosi developed the style and method that would make him, during the 60s and 70s, the greatest political filmmaker of his time,” wrote Michel Ciment for Criterion in 2004. “If Sergei Eisenstein could be considered the master of political cinema in the first half of the 20th century, Rosi, in a way his peer, offers a totally different approach to the realities of power…. Rosi, though able to provoke deeply sensitive reactions from his spectators, always manages to make them think by tracking down and exposing the lies that obscure the inquiries and the scandals of our societies. His filmography can be viewed as a vast panorama of the historical past of his country, as well as its present.”

In Salvatore Giuliano, “Rosi had taken the immediacy of neorealism—its quasidocumentary presentation of real people, in real locations, acting out real social problems—and merged it with a Wellesian love of showmanship, melancholy, baroque contrivance, and enigma,” wrote Stuart Klawans for Criterion in 2006. “Nowhere is this combination more outlandishly theatrical, yet absolutely authentic, than in Hands over the City, where actual members of the Naples City Council, playing themselves, in their own chamber, lift up their arms in protest to cry, ‘Our hands are clean!’—a bit of acting that they must have performed twice, so that Rosi could film it in long shot from the front, and then cut to a closer, more emphatic view from behind. Released in 1963, Hands over the City was the second great film in Rosi’s political series. It fully confirmed Rosi’s stature, winning him the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, while showing his newfound audience how masterfully he could work in the place he knew best, his native Naples.”

“Creating an effect of pity and terror unique in Francesco Rosi’s cinema, The Moment of Truth ought by rights to be counted among his finest achievements,” wrote Peter Matthews for Criterion in 2012. “On its original release in 1965, Pauline Kael acclaimed ‘the beauty of rage, masterfully rendered in art,’ the anonymous reviewer for Time magazine almost identically celebrating a work of ‘brutal and paralyzing beauty.'”

Updates: “‘With Rosi we lose a master, a man of culture, a lucid eye with a great commitment to civil society,’ Rome Mayor Ignazio Marino said.” Steve Scherer reports for Reuters: “Sophia Loren and Omar Sharif were stars in Rosi’s 1967 film More Than a Miracle, a fairy-tale story of romance that diverged from his more serious work…. He was awarded a second Golden Lion in Venice in 2012 for his career contribution to cinema.”

“1974’s Lucky Luciano revealed the political and social networks surrounding the infamous gangster,” writes Ariston Anderson for the Hollywood Reporter. “His 1981 film Three Brothers earned him an Academy Award nomination for best foreign language film. In 1984 he directed Placido Domingo in an adaptation of the opera Carmen, which was nominated for a Golden Globe for best foreign language film. He continued to direct until 1997, with his last film The Truce, starring John Turturro as Primo Levi. The Berlin International Film Festival honored Rosi in 2008 with a career tribute and a Golden Bear for Lifetime Achievement.”

“After starting out as an assistant to Luchino Visconti in the late 1940’s Naples-born Rosi kicked off his directorial career at the 1958 Venice Film Festival where his first feature La sfida (The Challenge), which delved into the intricacies of the Neapolitan mob scooped the Special Jury prize,” writes Variety‘s Nick Vivarelli. “In a 2012 interview with Variety, Rosi cited the influence of both neorealism and American directors Elia Kazan and John Huston on The Challenge, which is about a small-time Neapolitan hoodlum who challenges the crime syndicate over control of the local vegetable market. But he also noted that by his third feature, Salvatore Giuliano, his aesthetic had evolved toward ‘my own type of linguistic invention within critical realism,’ he said.”

Update, 1/11: The Mattei Affair “investigated the career and mysterious death of Enrico Mattei, president of Italy’s state-controlled petroleum concern,” notes David Robinson. “To emphasize his role as investigator, Rosi chose to show himself at work on the film within the film. The risks of this kind of investigative work were dramatically highlighted when one of Rosi’s researchers, the journalist Mauro De Mauro, vanished forever, after apparently having found out too much about the case and, incidentally, about the drug traffic between Sicily and the US. Mattei was played by Gian Maria Volonté, who worked in five of Rosi’s films, and in whom Rosi valued ‘not only a political consciousness but also a profound consciousness of the psychological structure of the character.’ Volonté collaborated on the research for the film.”

Further down that same page in the Guardian, John Francis Lane: “I treasure many experiences of watching Francesco Rosi at work, not least from my cameo roles in The Moment of Truth and Lucky Luciano, and interviewing him for a BBC Arena film in 1985. But the most extraordinary event happened in Sicily in 1962 when he organised a special screening of Salvatore Giuliano for the people of Montelepre, the village where the bandit was born.” An extraordinary anecdote follows.

Updates, 1/13: “Rosi made historical films (More than a Miracle, 1967), war pictures (Many Wars Ago, 1970; The Truce, 1996) and family dramas (Three Brothers, 1980) in a directorial career that spanned almost four decades,” writes Pasquale Iannone for Sight & Sound, “but he will be remembered above all as the master of the ‘cine-investigation’ and an influence on several generations of artists, including the likes of Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Roberto Saviano and Paolo Sorrentino.”

“As a filmmaker, Rosi was closer to being a documentarist, or psychoanalyst or connoisseur of the semiotics of political conspiracy,” writes the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw. “Rosi’s legacy is a small but persistent strain of satirical skepticism in Italian cinema and cinema about Italy: with movies like Sorrentino’s Il Divo (2008) about the occult mystery of Guilio Andreotti and his links with crime or Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini, about that director’s possibly politically inspired murder. Rosi was a fierce, cerebral, subversive talent whose works still resonate.”

For Cineuropa, Camillo De Marco reports on Monday’s memorial service, noting that, for Sorrentino, “Rosi ‘was one of the greatest directors in the world, not just in Italy,’ just to cite one of the many comments made following his death. ‘There are some filmmakers, very few, who create worlds, who can build worlds by inventing techniques and styles. He was one of these. He was a great innovator, a model for all those who sought a certain type of film, that’s not only linked to politics but that’s also an exploration of humanity.'”

“In addition to being a director and screenwriter for his own films and those of others (he wrote Bellissima for [Luchino] Visconti and The Bigamist for Luciano Emmer), Mr. Rosi had a brief career as an actor, appearing in three films,” writes John Anderson in the New York Times. “‘He was a wonderful actor,’ [John] Turturro said. ‘He helped you physically as an actor. If he had trouble explaining something, he could act it out, and all the actors understood.'”

The Berlinale’s announced that it’ll screen Uomini Contro (Many Wars Ago, 1970) during the festival’s 65th edition. “Rosi’s anti-war drama takes place on the mountainous Austrian-Italian front during World War I.”

Update, 1/15: “In December 2001, through the good offices of my friend Lorenzo Codelli, I arranged an interview with filmmaker Francesco Rosi for my book Revolution!, about cinema in the 60s,” recalls Peter Cowie for Criterion. “Rosi lived for decades in the fashionable via Gregoriana, above the Spanish Steps in Rome. His hushed apartment gazed out over the city, and his sitting room was crowded with books, magazines, and memorabilia. A servant brought tea as we talked, Rosi developing his complex arguments and unerring dialectic in a French that was so forceful and clearly articulated that even I could understand it. ‘I am a passionate man,’ he said, ‘but with the ambition to be rational at the same time—and my passion is typically Neapolitan. There’s a conflict between the passion and rationality. I live situations with passion, but I try to deal with them in a rational manner.'”

Update, 1/18: Rosi “not only understood and explained the shadows and labyrinths of what happened to be my formative years—in Italy, learning how politics work—but had an uncanny ability to predict what would happen next.” Ed Vulliamy in the Observer: “In 1976, he released the best political thriller of all time, Cadaveri Eccellenti (Illustrious Corpses). Based on a novel by Leonardo Sciascia, it depicts serial assassinations of judges by—the state insists—revolutionaries on the extreme left. But, it emerges, the judges are being killed by agents of the state in order to justify repressive measures. A subplot tells the story of the Communist party holding back the truth it learns, in order to avoid unleashing revolution. Rosi had exactly predicted—and chillingly depicted—the so-called ‘strategy of tension’ that came to define those years in Italy. His prescience was extraordinary.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.