After winning an award at Cannes for his first film, Pather Panchali (1955), Indian auteur Satyajit Ray felt he deserved an upgrade. Specifically, he wanted a crane. The script for his next film featured an ornate music room, and Ray wanted to capture its glory through awe-inspiring overhead shots. He got his wish, but at great cost.

One day, after the end of shooting, the bulky crane was being loaded onto a truck when it toppled over and fell down. One crew member died; another was crippled for life. Ray was struck with remorse as a result, and, according to film historian Philip Kemp, realized, “All this would not have happened if I had not set my mind on those overhead shots.”

Guilt of a similar kind pains the protagonist of The Music Room (Jalsaghar), the film Ray was working on at that moment.

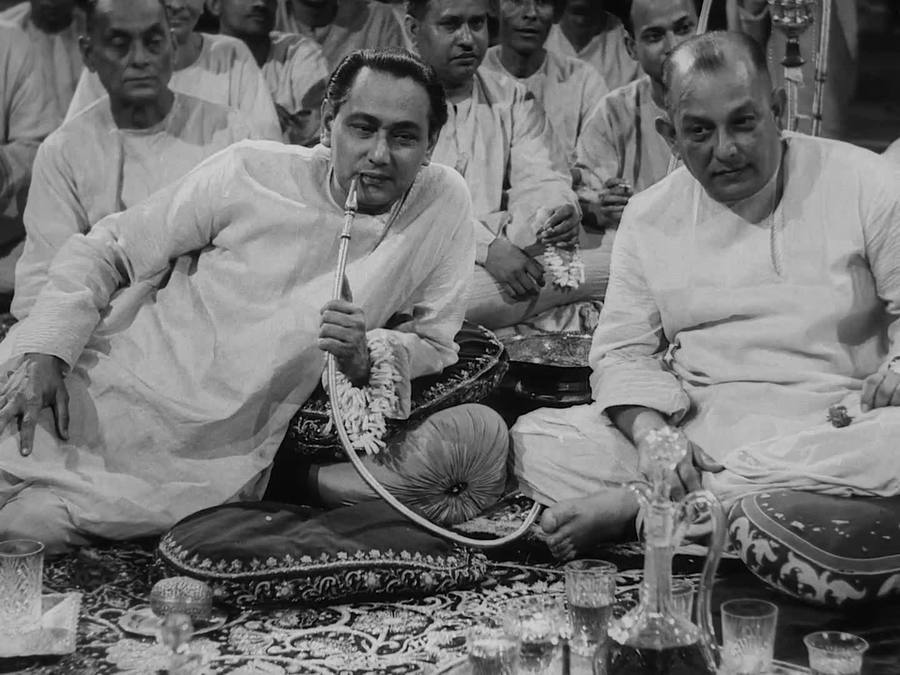

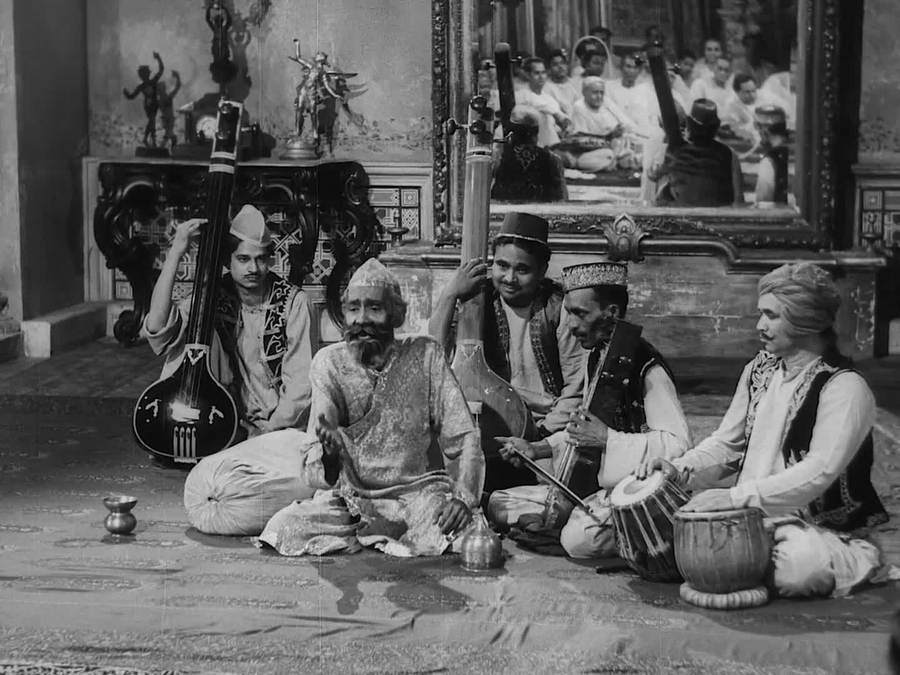

Biswambhar Roy is a zamindar (landed gentry) in the province of Bengal in the late twenties. The government is abolishing the system that provided him sustenance, flooding has diminished the size and worth of his holdings and his finances are thinning away. Yet Roy refuses to acknowledge these truths, preferring instead to spend his days reminiscing about past glories or attempting to recreate them. He is obsessed with the music room in his bungalow, where, in better times, he organized numerous musical performances and hosted the town’s elite.

He is also extremely petty and spiteful. Roy represents the old school, aristocratic way of life. But his neighbor, Mahim Ganguli, is part of the nouveau riche, an ambitious entrepreneur who is making his own fortune. The ascendance of Ganguli rattles Roy, who wants to preserve his supremacy: if not in monetary holdings, then at least in prestige.

In a great moment (from a film peppered with them), Ganguli visits Roy to invite him to a performance in the businessman’s house. Roy pretends to be busy in his newspaper, forcing the guest to repeat his request. Maintaining a glittering façade is of paramount importance to the landlord, even if that entails fighting a battle he’s already lost.

Roy declines the invitation, claiming he’s organizing a performance the same evening. His trusted servant, well aware of the household’s declining fortunes, is stunned. Roy mortgages his wife’s jewels to stage this extravaganza, and calls his wife and son—away to visit an ailing relative—back. They perish in a cyclone on the return journey, and Roy’s stubbornness leaves him alone in the world.

The Music Room is a bleak portrait into a sad life. The stark black-and-white cinematography by Subrata Mitra, Ray’s regular collaborator, is perfect for the somber mood of the piece. The camera works its charm from the first frame itself, as we see the lumbering frame of Roy slumped in a chair on a desolate balcony, staring out into emptiness. When adding The Music Room to his “Great Movies” series, Roger Ebert called this “one of the most evocative opening scenes ever filmed.”

The pathetic nature of Roy’s character comes across so vividly because of Chhabi Biswas’ performance, which induces our sympathy while repulsing us. Biswas’ lugubrious demeanor and puffed-up face cannot detract from the haughtiness of his smile and arrogance of his eyes. He infuses blue-blooded confidence into a character whose actions are that of a petulant child. At one point, he chides his neighbor’s aspirations by calling him “a dwarf reaching for the moon.” That may be true, but Roy is a giant who refuses to come back to ground level.

Ray devoted a vital part of his filmography to exploring the consequences of social progress, especially when the times race ahead while some people stay behind. He would return to this obstinacy twenty years later in The Chess Players (1977). The protagonists of both films are like proverbial ostriches, shoving their heads into the sand to ignore the turbulence afoot outside. While zamindar Roy loses himself in the portraits of his illustrious ancestors, the Nawabs in Chess Players can barely look up from their hookahs and chessboards.

However, the latter attempts biting sarcasm and thus somewhat distances itself from proceedings on screen. The Music Room is much more intimate and, consequently, more moving. There is little between Roy’s despair and us.

Earlier this year, another film came out that was about a flamboyant character who happened to be living in an epoch well past the one he belonged in. Like the exuberant Gustave H. in Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, Roy’s world had ended long before he entered it. But, unlike Ralph Fiennes’ eccentric concierge, Roy could not sustain the illusion with anything resembling grace.