[For more of our “Fifty Days, Fifty Lists,” see “Why Lists?” here on Keyframe.]

A common misunderstanding: often, when people casually use the word “soundtrack” in relation to films, they refer only to the music—or, worse (because even more distant from the material film itself), the cleaned-up, pristine CD of the musical score, which usually bears scant relation to how that music was used, performed and mixed in the movie. (“I collect soundtracks” is a misnomer you often hear.) But cinema soundtracks are a fused totality of voices, music and noises. Here is a swift historic panorama of some of the possibilities.

Dickson Experimental Sound Film (1895)

The adventure of sound cinema starts with music and dance. In this early experiment (not publicly screened in its time) that counts as a historic ‘first’, William K.L. Dickson (collaborating with William Heise) sought to synchronize sound and picture. All the mechanisms, and even the mechanic himself, are visible: that’s Dickson in the flesh playing his violin (a tune from Jean-Robert Planquette’s operetta The Chimes of Normandy) into the large, suspended gramophone horn. And then there’s the charming spectacle of the two guys dancing alongside him, plus another member of the crew making a split-second appearance in the background. Reassembled for our day by Walter Murch and Rick Schmidlin, using the materials preserved by the Edison National Historical Site, it will give you a musical “ear worm” that is hard to shake.

Sound Stills (1975)

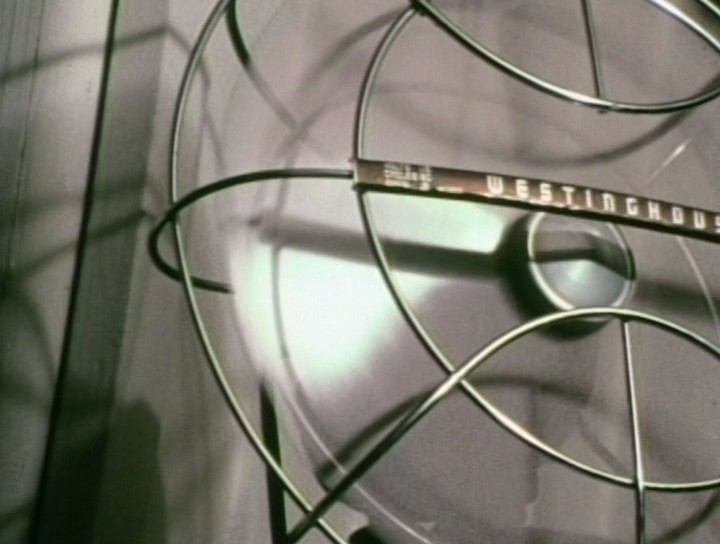

Chuck Hudina is a California-based artist whose early works of the 1970s were in experimental film and documentary, before moving more into collaged objects and photography. His stated aim concerning his present photographic work—”to record what is, unsympathetically and without comment”—can be related back to the beguiling Sound Stills. Hudina fixes on what theorists today call sound events—physical actions in film that depend as much on the sound produced as the visible gesture performed. Tapping on a metal bar, showering, a needle registering a rhythmic loop of static at the end of a vinyl record on a turntable, an electric fan blowing, a swinging hammock, starting up a car and driving out of frame… Hudina, in the manner of structural movies of the 1960s and 1970s, unfussily assembles a progression of moments that make us wonder, anew, about the small miracle of synchronizing images with their “direct sounds,” before the era of massive post-production took hold.

Nocturna Artificialia (1979)

“The sounds, so prolonged now, that pause mechanically to line the wooden streets below.” The Quay brothers, Timothy and Stephen, are well-known for their remarkable, hand-crafting skills in visual animation: surreal puppetry, miniature sets that seem to have been assembled from historic ruins, uncanny patterns of movement. But their way with sound is no less important, and no less unsettling. Their early Nocturna Artificialia (‘Artificial Night’) is, like several of their best works, a disjunctive mixture of literary inspiration—phrases like the one quoted at the beginning of this paragraph divide the piece into its parts—and ‘pure cinema’ at its purest, devised frame by frame. In this haunting, funereal tale of a typical ‘man without qualities’ absorbed into the city around him, it is the endlessly extended sound of a streetcar—creaking, rattling, groaning—that burns itself into our sense-memory.

Mimi (1997)

The filmmaking styles and themes of wife-and-husband team Lucile Hadzihalilovic (Innocence, 2004) and Gaspar Noé (Enter the Void, 2009) are quite distinct, and yet overlapping in many small, intricate details. In Hadzihalilovic’s Mimi (a.k.a. La Bouche de Jean-Pierre or “Jean-Pierre’s Mouth”), a subtle and disquieting tale of a young girl’s relationship to the sexuality of the less-than-angelic adults around her, we can hear something that definitely unites these two gifted, inventive directors. It is the sound—half musical, half “industrial”—of room tone, ambient noise. It is rarely a loud, dramatic clatter or clang; far more often, it is the low, droning buzz or hum of a ventilator, a neon light fixture, an electric sign, a refrigerator… And when Hadzihalilovic, at the start of Mimi and at punctuating intervals throughout, assembles a montage of these strange “sonic spaces,” it’s almost an atonal symphony: the ground-tone of (as the opening credits declare) “France today.”

Neighboring Sounds (2012)

One of the most striking feature debuts of recent years, Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighboring Sounds maps a fraught, urban space (the coastal city of Recife, Brazil), where paranoiac security systems in every well-off home fight a hopeless battle against street culture, crime and chance events. The novelty of this film lies in the way it marries a precise, spatial architecture with the sounds, domestic and dramatic, that carry, permeate and interconnect everybody and everything in a ‘network narrative’. The streak is on from the first frame post the opening credits: percussion builds in layers over a series of metronomically edited black-and-white stills, and then we trace, step by step, the interlocking spaces of the neighborhood, each new shot announced by a dull, thudding noise whose source is as yet unseen. . . .