Some come in planes, but most of the attendees of the Valdivia Film Festival (usually film students, fanatics and representatives of the blooming Chilean Film industry) come from Santiago or Valparaiso in bus. It’s a twelve-hour trip without many stops, so it already puts you in the mood for the experience that’ll be, not because it’s boring, quite the contrary, but because it entrances you. The films, the people, the landscape of Valdivia are something to be reckoned; they come to you as if they were part of a conspiracy, as if you just lived an episode of Twin Peaks. Once you come, you won’t forget it, and you’ll want to come back every year.

That’s what happened to me, because there’s no other way in which I would travel more than six hours in any kind of earthly device without stopping. Valdivia has captured me, and the only thing I can do now is enjoy the week I spend there every year, and try to get a new lesson every time I’m there. After twenty-one years, the Valdivia Film Festival has become some kind of ritual for every film buff not only of Chile, but surely and even more now than ever, for the rest of Latin America.

If you have enough luck to settle in a place that is near one of the five places in which movies are being shown for the six days of October, you’re pretty much settled to have a complete experience: the walking distance between one screen and the next is never more tan fifteen minutes walking, and it’s always a pleasure to wander around in the streets, walk the bridge that crosses the Calle-Calle river, which is also the main place where you can watch the majestic South American sea lions, who used to roam the streets of Valdivia in times of the festival, until they were exiled to a raft in the middle of the river, where they take sun and bath all day.

In between films and walks between screens one can find bars, pubs and restaurants in which the obligatory snack is the “crudo” (literally “raw,” chopped-up raw meat put on a piece of bread) and the official beverage is the local-brew beer. It is there that you can find yourself eating alongside fellow critics or the invited filmmakers, or even the first-time directors who are trying to make their first big splash, following the route of directors like Miguel Gomes (Tabu, Our Beloved Month of August) and Tizza Covi/Rainer Frimmel (La pivellina, Shine of Day).

It is there, alongside a big plate of fried fish and mashed potatoes (for those eating on a budget, like every other film student coming here), that conversations and debates arise, like those who are looking forward to the 16mm projections of the works of Marie Menken (Go Go Go) and Santiago Álvarez (Now), or those, like myself, who decided to miss the opening of a big film to attend the 16mm projection of The Lost Patrol, a 1934 John Ford film, shown in a print of the time with no restoration whatsoever. While not being quite as talked about as other Ford films, this warrants a re-evaluation, even if it can be uncomfortable in certain sequences for its racist undertones.

The Lost Patrol can be qualified as some kind of proto-slasher, where a big group of people (a British troop in World War I) end up being killed one by one until there’s one ‘final girl’ (or man, in this case, making it already a subversive slasher) by a group of unknown killers (the Arabs). It even manages to entice horror in the viewer, as we see the ruthless ways in which our dear characters are being shot and/or maimed by the fierce adversaries, and it even plays with the comedic effect that those deaths have in the viewer, due to the circumstances in which they occur. I might be having a case of hyperbole, but that’s what happens when you see films in Valdivia and in such a precious print.

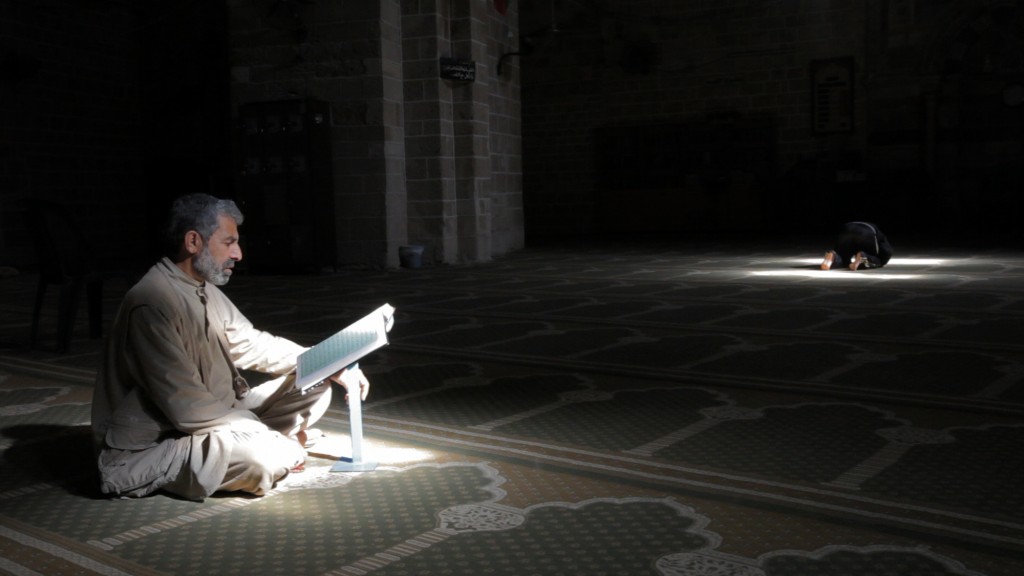

Every film festival must, obviously, have its own competition; and Valdivia has three: International, Chilean and Shorts. In the International Competition there is a mixture of documentaries from all over the world and fictions from Latin America, England and France; mixing important subjects, like the issue of Palestine and the Gaza Strip in the episodic Striplife, directed by Teleimmagini, a group of Italian filmmakers that went out of their way to film different characters in the Gaza strip, a woman of a nomadic tribe that can’t move anymore, a young rap artist that tries to survive even if its currently prohibited to rap in the streets of Gaza, or a female TV news reporter that tries hard to put the situation of her people for a wide audience. The film calls attention to itself due to being an important issue, but its execution doesn’t seem any different from your run-of-the-mill television report, with its ‘human angle’ and all; even in its scattershot nature, with many characters, not all of them being equally interesting, it still is worth seeing for those who can’t seem to believe the current situation of Palestine and the refugees.

A better film is the Chinese/American documentary The Iron Ministry, filmed in three years of train travels through China, It manages to create a sociological and political survey of, more than its economical growth or its culture, of The People. The one in the name of the country, ‘People’s Republic of China’, one that is more individualistic than anyone may think: young Chinese men disappointed with the way in which The Party is taking care of economy and specially The People, think of fleeing the country in hopes of a better future, while also saying that change inside the country is impossible as one of them says: ‘everyone can eat hot buns, there won’t be a revolution’, which might be the most important phrase uttered in a film in 2014. The film is a visual exploration of the spaces that are left in that unknown China, just like the camera that moves along and squeezes among the huge crowds in the overbooked cabins and jumping and stepping through the big mounds of trash that fill the floors of the train carriages.

Two Chilean films also take part in the International Competition, the still unseen Mar (Sea), a co-production with Argentina and the second feature length film of Dominga Sotomayor, winner in 2012 of the biggest prize at the Rotterdam Film Festival (and also winner of Best Picture in Valdivia the same year) From Thursday Till Sunday; and the film chosen by Chile to represent us at the Oscars, To Kill a Man, winner of Sundance World Jury Prize for best picture and directed by the highly awarded Alejandro Fernández, following the classic structure of a vengeance thriller, but with a twist or two when it comes to the way in which it formally represents it, and its use of non-professional actors (with one exception for the role of the thug). It’s been shown in many festivals and it has been reviewed before, so there’s not much else to say besides that it is a worthy possible winner of the big prize this year.

The Chilean Competition is usually the place for first time directors and films made by students as their graduation project, that and the oddity of the year, Santiago Violenta, directed by action film director Ernesto Díaz Espinoza (Redeemer, Bring Me the Head of the Machinegun Woman). Among those shown so far (the festival will run till this Sunday), Canción sin letra (Unknown Song) is a comedy in the style of those made famous in Sundance, with quirky and weird characters that twist around with romantic relationships between them, all surrounding a band without a name that brother, sister and a friend form one day; the structure is weak and there is incest without much reason for it to really exist, but it manages to catch your attention throughout the whole film.

La Visita (The Guest) is the other Chilean film that has been shown, which follows a new trend of having transsexual characters as protagonists, in this case a son that comes back to the house in which he grew up, but he comes back as a post-op trans woman. There are some obvious scenes, especially regarding clothing and the fact that she comes back because of the death of her father. The house is a strange place, almost if it was too consciously rendered to be considered a character in itself, with corners and mirrors that double the images and makes the abuse of certain tropes regarding genre identity a bit laughable in the end. There’s still a promise of a great director here, Mauricio López has a quiet and incredible control of his camera, as well as the composition of the shots.

We can hope that as the festival progresses the true wonders appear, as well as the more awaited screenings start to loom in the future: Adieu au language 3D, Pasolini, Horse Money, Jauja and a 35mm copy of the giallo Torso. Valdivia is the film festival that will make more people talk in the future, and you had a glimpse at it today.