Like great existentialist fiction, films noir have used death to explore the finitude of existence. However, a great many of these have used the death of a character to explore the way the past makes itself felt in the present, or the return of the repressed. The most dramatic and unsettling way death is used in film noir is when they explore how a past death, coded as a traumatic event, affects the present. Two recent neo-noirs, Sun Don’t Shine (2012) directed by Amy Seimetz and Between 2 Deaths (2006) directed by Wago Kreider, explore the noir death trope in radically different ways, depicting how the past can never be entirely repressed.

In Sun Don’t Shine, death is explored within the context of a “couple-on-the-run” sub-genre of noir that began with Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once (1937). Three essential noir films from this sub-genre are Gun Crazy (1950), Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Badlands (1973) along with subsequent derivative films used the couple-on-the-run narrative to explore the couple’s relationship in the midst of getting chased by the police for their crimes. What is interesting about Sun Don’t Shine is that the director, Amy Seimetz chose to begin the film with a crime that has already taken place, and the film explores this crime’s effect on the couple. Not only are these two a noir couple of the “couple-on-the-run” type but they are also a “doomed couple.” The doomed couple, Leo (played by Kentucker Audley) and Crystal (played by Kate Lyn Sheil), in Sun Don’t Shine carry the evidence of the crime with them on their journey so there was nothing at the murder scene for the police to investigate, thus no “Law” actively searching for them. The way morality figures into this narrative is through Leo’s guilt and the knowledge that he is a carrying his victim’s body in the trunk of his car, a constant reminder of his sin. The dead body in their car transforms their car into a moving coffin. For Leo and Crystal, the dead body is a constant reminder of the inevitable end of their lives, their finitude, their crime and their past.

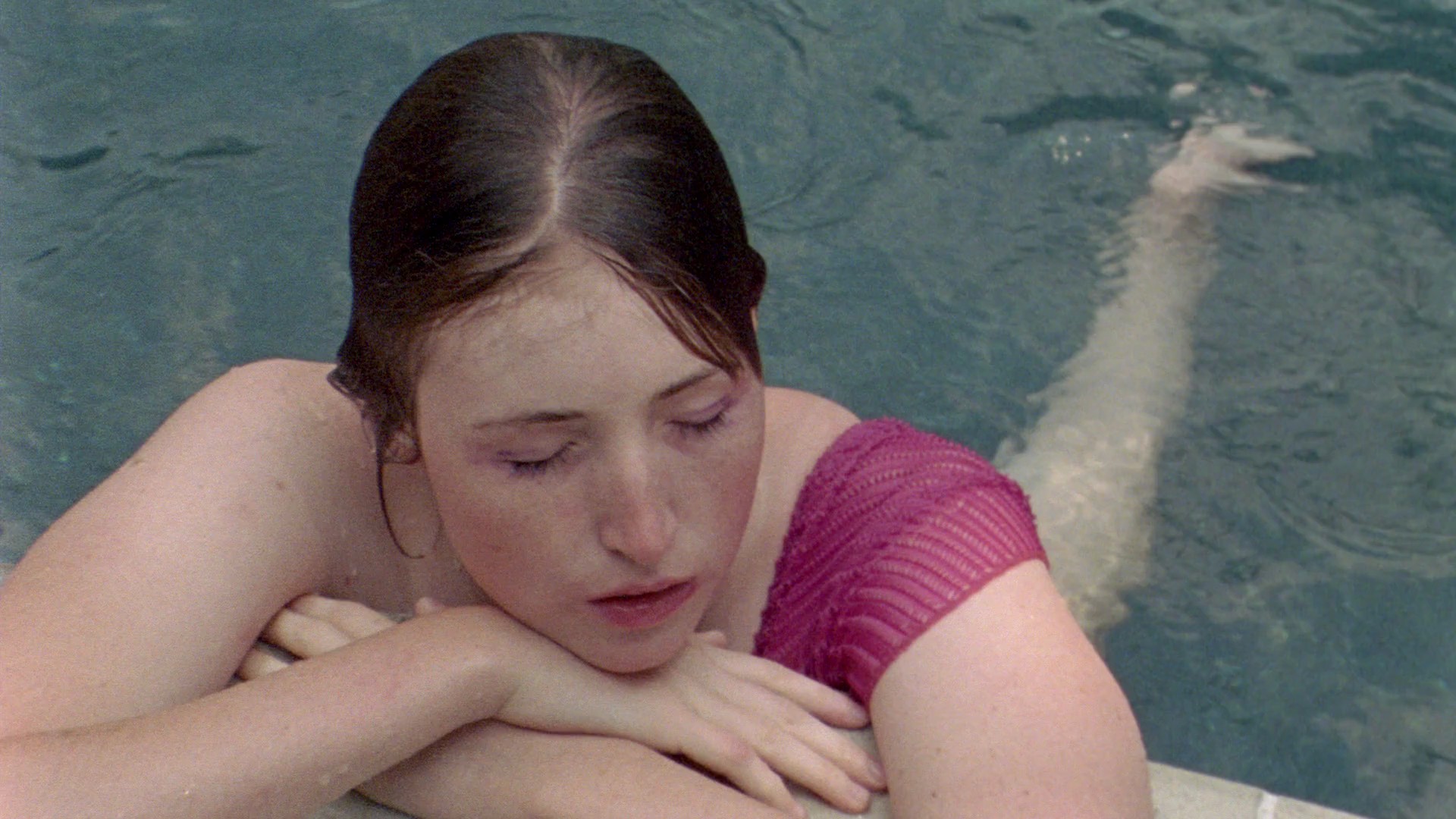

Much like the couple-on-the-run noir films mentioned above, Sun Don’t Shine uses the car as the vehicle for the narrative, embodying and representing what propels the narrative. Rather than being simply a metaphor for the movement of narrative, the car makes the movement of the narrative possible. Movement, momentum, life are all contrasted to stillness, stasis and death. The inevitable end of the film itself meaning literally the end of the images through the projector (whether they are on celluloid or digital files) and the end of the fictional characters. To stop moving is to die for the characters and for the narrative. Death (and the death drive) in Sun Don’t Shine is then simply a particular example of the death drive inherent to all narrative films. Like many films noir, Leo and Crystal’s eventual end, which is not their death but their arrest, represents the stillness that all narrative films long to reach. The final scene of the film happens shortly after Crystal has deserted Leo is much more anticlimactic than Gun Crazy, Bonnie and Clyde, and Badlands. Crystal trespasses into a stranger’s yard and slips into a pool. She rests at the edge of the pool, slowly kicking her feet. “Do you want me to call the police?” the owner of the house asks. “Not yet,” Crystal responds as she lays her head down to rest and closes her eyes, her first moment of peace in the film. Her stillness symbolizes the impending end of the narrative, the culmination of the death drive.

In a rather different type of cinema, but one that is certainly related to Seimetz’s neo-noir, Wago Kreider has been exploring cinematic memory through various video art pieces. In Between 2 Deaths, Kreider uses scenes from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) combined with shots of the same location taken in 2006. D’entre les morts, the title of the novel that Hitchcock adapted into Vertigo, is an apt name for this story, which literally means “from the dead.” In Vertigo, Scottie is a detective desperately trying to resurrect an image that no longer exists, the image of Madeleine that has died and that will die again. The return of the repressed is depicted as the death of the image of Scottie’s desire, one that has already died but lives again when Scottie resurrects Madeleine’s image through Judy.

Between 2 Deaths takes the narrative raw material, meditation on death, and transcodes it into the form of the film. Kreider intercuts images of Scottie stolidly walking through a cemetery with quick dissolves to empty spaces fifty years later. Scottie’s image disappears and reappears every few seconds, making his body in the frame feel ephemeral, as if it might dissolve into nothingness before our very eyes. One space filmed across two moments separated by time, presented nearly simultaneously, perfectly depicts the inscription of past images in the present. Much like how Scottie was determined to resurrect the image of his desire, Between 2 Deaths literally resurrects Scottie’s images from Vertigo, visually depicting the return of the past and living ghosts of cinema’s history in the present.

Between 2 Deaths also testifies to the lasting influence of Mark Rappaport’s cinema. Exterior Night (1993) is one of the best neo-noir films made in the nineties and demonstrates how far-reaching noir as a cinematic phenomenon has become in cinephilia. Both Exterior Night and Between 2 Deaths reuse images from previous films noir to explore death and memory. In Exterior Night, Rappaport combines original color footage with archival footage of sets or backgrounds from iconic films noir like The Maltese Falcon (1941), Mildred Pierce (1945), The Big Sleep (1946), Possessed (1947), Dark Passage (1947) and Strangers on a Train (1951) (among many other films). Rappaport, along with cinematographer Serge Roman, stage contemporary actors against scenes set in streets and lounges from the classical era of film noir. The contemporary actors and scenes for Exterior Night are shot in color but the black-and-white images always find a way to enter the frame whether it is through windows or TV sets.

Exterior Night is about the resurrection of dead images and the persistence of the past in the present. The main character, Steve (played by Johnny Mez), walks through dark streets that he feels a certain intimacy towards but admits to have never seeing them in his waking life. Steve wants to understand these recurring images so he visits his parents, who are made to look like idyllic parents from Eisenhower’s fifties. We discover that the key to Steve’s dreams is his dead grandfather, Biff Farley, a private detective turned writer and, according to this film, the most famous writer of the forties. Steve meets a beautiful blond woman named Sylvia who looks like his mother and his grandfather’s lover, Mona (all three characters are played by Victoria Bastel). They spend the night together, eventually returning to the scene of Farley’s death. This is a significant memory, one that Steve has never experienced himself but continually returns to all the while traversing various empty locations from film noir cinema as this memory replays itself in his dreamscape.

Film noir, whether you define it as a genre, mood, tone or style, is very much a type of cinema that is focused on death and memory. Exterior Night takes this narrative raw material and transcodes it into the very form of the film. Much like how Between 2 Deaths cinematically resurrects images from the past, Exterior Night is about this ghostly resurrection of images from film noir cinema. Whatever the changes noir undergoes in future cinema, it appears that filmmakers working in this genre have yet to exhaust the cinematic possibilities of exploring death on screen.