Far from the cinema of spectacle that multiplexes are currently showcasing, including the homoerotic aesthetic of 300: Rise of an Empire or a visit to Wes Anderson’s all star cast at The Grand Budapest Hotel, I’ve been making my way over cobblestone streets into unassuming arcades where smoke-filled stairways lead to conversations about revolution. Jeden svět (One World) is the world’s largest human rights film festival, showcasing one hundred six documentaries from across fifty four countries. Though audiences sit silently in darkened rooms, the act of viewing is never passive and the images are a far cry from entertainment. Exposing totalitarian regimes, exploring social, political and environmental issues and interrogating the relationship between technology and revolution, attending the festival is itself a political act, here in Prague, the true capital of Bohemia. Most screenings are followed by question-and-answer sessions with filmmakers, civic activists or journalists specializing on the given topic, encouraging discussion and transforming the auditorium into an arena for instigating change.

Though the festival refuses the glitz and glamour of the red carpet and rejects the moneymaking markets that characterize Cannes, Venice and Berlin, a sense of occasion was still present on Opening Night. Where other festivals might indulge in artifice and excess, however, One World presented the international premiere of a sobering documentary on the 2012 Marikana massacre, Miners Shot Down. Not exactly a film to put its audience in the mood for a party, the reception was coloured by somber reflection. What does it mean to enjoy a banquet after literally watching people die? Wiping away tears that flowed freely in the dark, I found myself entering the light of the after party with a heavy heart. Moving images tell stories in a number of ways, and here, at One World, it was clear that they would act as a tool to confront audiences about the current crises of humanity.

Rehad Desai’s Miners Shot Down revealed a state of bloodshed in South Africa that echoes the days of apartheid. A week of non-violent demonstration by Lonmin mine workers protesting for better pay ended in a shroud of darkness with thirty deaths, at the hands of a system determined to keep its stranglehold on the lower classes. Featuring staggering police footage of the massacre, Desai presented his audience with acts of violence, but also the inaction of those who witnessed the deaths, filming or standing by, as protesters died slowly, ambulances refused access to the scene. Watching this material was ethically devastating and a stark reminder that the act of viewing is never passive.

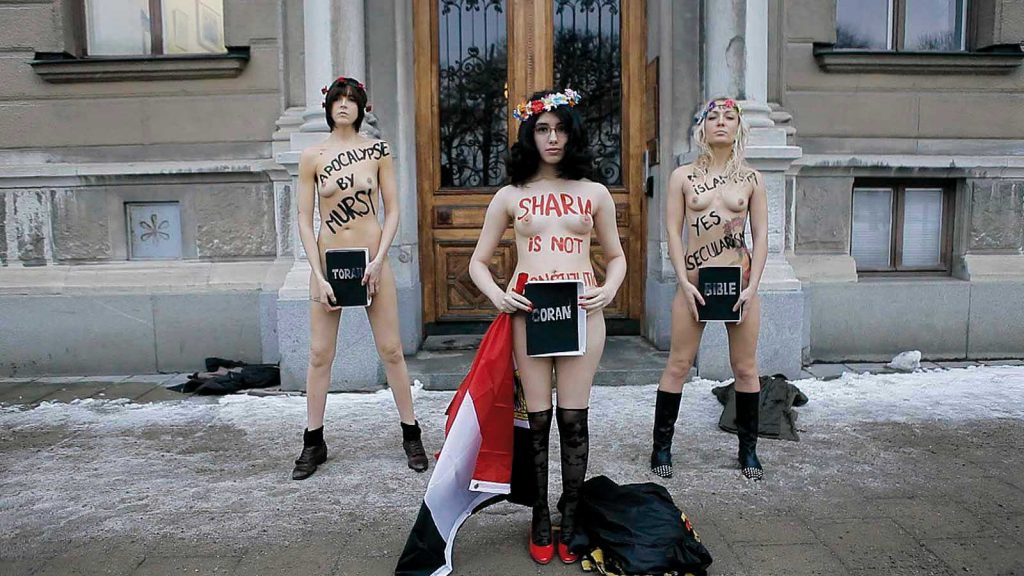

Of course, starting the festival with such shocking and powerful images wasn’t only to jolt us to attention; exposing injustices was a means of raising awareness in order to effect change. In the opening address, we were told that despite the blood and tears, it’s important to see hope where it exists and to use it as a gateway for positive change. Arash and Arman Riahi’s Everyday Rebellion would perhaps have been a better choice to illustrate this point. Taking its examples from a number of recent rebellions spanning the Occupy movement, the uprising in Tahrir Square, the state of play in Syria and Femen’s dissemination throughout Europe, it preached non-violent protest as a successful historical model for political and social reform.

Telling us that “Movements are in conversation with each other,” and that “If you don’t rebel you’re accepting collapse,” the film showed everyday people taking issues to the streets. Surveying academics and activists, its findings were that non-violent campaigns took an average of two and a half years to co-ordinate. Being organized and accepting that change takes time is key to successfully executing any rebellion. Though the film glossed over some of the more intricate issues involved in each of the conflicts it characterized, it didn’t shy away from the harsh realities of advocating freedom either, stating openly “There’s never been a movement where people haven’t had to go to jail.” Amounting to a sort of revolutionary tasting platter, Everyday Rebellion attempts to universalize disparate issues better explored in stand-alone films like Jehane Noujaim’s The Square and Kitty Green’s Ukraine is Not a Brothel.

The Square follows four individuals who represent different religious, national and gendered roles, each stifled under the totalitarian regimes in Egypt: first under Hosni Mubarak, then the armed forces and finally the Muslim Brotherhood. Starting with the image of an eight-year-old boy who believed “There was no hope for a better future in this country,” and ending with its focus on a new generation of children who now play protest to “bring down the regime” as a game, the film searches for a silver lining amid the blood stained streets of Cairo. Punctuated by the changing seasons, the film deftly explores years of struggle through a cyclical framework; spring brings hope in the lead up to summer where conviction reaches boiling point, before hope wanes in the fall and the clutches of the regime chill the hearts of the people when winter sets in. But for all its uncertainty and with revolution lingering in the air, Noujaim’s film also posits the struggle for freedom as an ongoing story. A mural accompanies each transition, every brushstroke serving as a reminder that despite their long history of internal feuding the future for Egypt is a picture yet to be painted.

The most perplexing internal paradox, however, might be in the formation of Femen, Ukraine’s feminist agitprop collective who protest the patriarchy with painted slogans across their bare breasts. Before its most internationally recognizable member, Inna Shevchenko, fled Ukraine for political asylum in France, where Femen has now established more organized headquarters, the group started out under curious auspices. Anna Hutsol is credited as the founding member, and the group’s beginnings—from which Green takes her title—was in protest of the world’s perception of Ukraine as a bordello for sex and human trafficking. As Green interviews each of the girls involved—including some whose refusal to go topless meant being forced to leave the group—the cracks begin to show. The girls joined as teenagers, many of them uncertain about their own feminist convictions. When Green pulls the rug out and reveals Victor Svyatski, the self-professed patriarch of Femen, as the mastermind behind their demonstrations, their actions are de-politicized and reduced to spectacle.

As with Miners Shot Down, what we see is confronting not only because it is shocking, but also because it reveals a system so steadfast in its oppressive agenda that the opportunity for real change feels like a distant ideal. Some issues seem too big to tackle and there’s no better example of this than Alexander Gentelev’s look at the true costs of the Sochi Winter Olympics in Putin’s Games. Not only did the games blowout financially from Putin’s projected twelve billion dollars to an excess of fifty billion, but many residents were made homeless and lost their livelihoods in the wake of compulsory acquisition of land and businesses in order to better serve the construction of roads, housing and stadiums for the games. Unfortunately, Gentelev’s approach, though entertaining, is more concerned with making a fool of Putin than addressing the social issues at the heart of the crisis.

Still shaken by the images from Opening Night, and constantly reminded by the city itself, where the resonances of WWII, The Cold War, the Velvet Revolution and anti-globalization protests ring out as often as the bell tower chimes, change has to start somewhere. The festival also includes a number of films concerned with the uses and misuses of technology as a tool for political dissemination. Through Yorgos Avgeropoulos’s The Lost Signal of Democracy we see outrage and resistance to government silencing of Greek public broadcaster ERT, after 75 years of continuous service, and through Cullen Hoback’s Terms and Conditions May Apply we see how online platforms are a double-edged sword; sharing our voices with the world means agreeing to privacy conditions that leave us wide open to state surveillance. What we start to garner is that the global tapestry of human rights obstructions begin and end with information. Showcasing more than one hundred films that set out to inform, One World hopes to start the conversation. So instead of sitting in the dark and crying my eyes out as if the screen were merely a platform for tragedy to play out, it’s important to remember that media is a tool. Each cobblestone I step over is a reminder of the words from Everyday Rebellion, “Don’t mistake tool and substance. The street is where the struggle can be won.”