Breaking the Frame is what Canadian filmmaker Marielle Nitoslawska calls an “‘über-documentary.” Her film is a very personal immersion into the world of perhaps the most unique American female artist, Carolee Schnemann. Creatively active for more than five decades, a pioneer in performance art and avant-garde film, Schneemann has dedicated her energy and self to “breaking the frames” of the art world. Unlike many documentaries, Nitoslawska’s film is not an attempt to create an objective, linear portrayal of the artist. Throughout the six years that took this project to blossom, her and Schneemann have become very close, and this intuitive understanding between them is reflected in the visual form of the film, as well as through other channels of its creative expression.

I met with Carolee and Marielle last October in Wrocław, Poland, where Breaking the Frame had its Polish premiere at the American Film Festival. They were also opening an exhibition at WRO Art Center at that time. Needless to say, the two are so used to each others’ company, I felt more like a moderator than an interviewer. Watching them engage in an emotional conversation might just have been one of the favorite moments of my whole journalist career. I could almost see “the magic” they both talk about,when describing their collaboration.

Breaking The Frame screens at Anthology Film Archives January 31 through February 6.

Keyframe: I was lucky enough to watch your film in the big screening room, on a special screening, just me and the screen. It was splendid.

Marielle Nitoslawska: It’s great that you had such a luxurious opportunity of watching the film. It is supposed to be watched like that, on a big screen, that’s the truth of it.

Keyframe: I can’t help but ask how did you two meet? What happened in that moment that led to this incredible project emerging?

Nitoslawska: Carolee, do you remember how we met?

Carolee Schneemann: Well, we have different versions, but I remember I saw Marielle at a concert and asked Daichi [Saito], turned out a common friend of ours that I was with, who this woman was. Then we met. She knew who I was, she’s put an excerpt of my film Fuses into her film Bad Girl—something I didn’t know that or have forgotten at that time. . . .

Nitoslawska: And my version is. . . .

Schneemann: [Laughs loudly. ]

Nitoslawska: . . . Is that after doing Bad Girl I wondered—if I was really to do my authorial film about the body, who would it be about? And of all the fabulous women I’ve met during the making of it I though Carolee was closest to me. Then Daichi told me that Carolee was looking for a studio in Montreal [Where Nitoslawska’s living. ] and she’s going to be somewhere, sometime. . . he took me there—it could’ve been a concert—so that we would meet. Then we had coffee together. . . and immediately hit it off.

Keyframe: When one artist is making a film about another, does the subject feel the usual urge to manipulate it? Did Carolee have a say in what Marielle was doing?

Nitoslawska: During the making of the film, which as you know took many years [six, to be exact], we saw each other very regularly and I would be talking to Carolee about the ideas I had and my thoughts on the project. But Carolee never ever saw the film until it was completely finished. She had no input whatsoever.

Schneemann: I had no wish to. I didn’t need to see it, I just trusted Marielle. In all my previous collaborations with filmmakers or writers I felt something was always getting deformed and I really needed to know how thing were going. With her I just said: ‘whatever you need—except for my grandma’s necklace!’

Nitoslawska: Anna, do you know the story of the necklace?

Keyframe: Unfortunately not!

Schneemann: We tell it all the time! It was so weird… Marielle would come and visit in my countryhouse in New York and go through papers and films… anything she needed, my diaries, everything, she just went everywhere. And then one night we’re going out to dinner and I see she’s wearing my grandmother’s necklace. And I say: ‘You know, you can do anything you want here, but if you’re going to borrow my jewelry, please ask!’ And she was aghast!

Nitoslawska: I was horrified! How could anyone even suggest such a thing! I have received this necklace from my great-aunt in Warsaw, ‘ciocia Duda’ [‘Auntie Duda’]. When I was a student at Film School I always stayed at ciocia Duda’s, and when she died, she left me this necklace that she received from some aunt of hers. And she’s never left Poland. And then Carolee pulls out her necklace that she got from her own grandmother. And they are absolutely identical.

Keyframe: Now I understand how unique your connection must have felt! Tell me more about the structure. . . or rather: texture of the film. Breaking the frame is on one hand very creatively independent, on the other very respectful of Carolee’s attitude towards material.

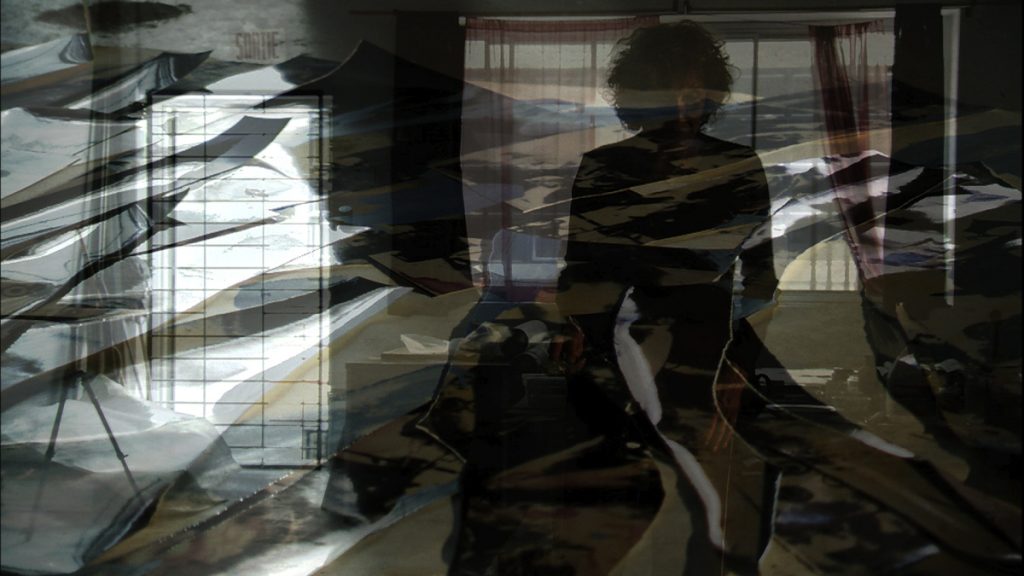

Nitoslawska: This issue was a very early decision. Obviously Carolee’s whole body of work is very much about the materiality of the medium, in its widest sense. Certainly working with the materials is very fundamental part of it. I was very interested in time, and how we associate it with film materials. Very early on I knew I don’t want to have a situation where there’s Carolee’s Super 8 films and then my new stuff. So there’s plenty of my Super 8 material in the film as well, so we can’t tell anymore what’s what. I didn’t want to have a dichotomy, I wanted to expose my process of searching for this film and Carolee’s work. And one of the ways I did that was through the incredible materiality and textural quality of the sound and image.

Schneemann: And also very intense, sharp editing. Everything is in proportion to my intention. I’ve just been so overwhelmed, there are sections and sections with no lyrics, just nature around the house. And then she cracks it, something breaks through, which is just how I like it. It has to do with my principle of collage, gestalt, tearing. When you rip a predictable element you’ll get something incremental. We never discussed this with Marielle. And this is a feeling of her own—within my material. It’s just been astonishing for me, it’s so coherent. It’s hers—but of my essence.

Nitoslawska: There’s a connection between us, a contact. It’s something that one either has or doesn’t. The film medium is perfect for it.

Schneemann: In the last scene of the film I was carrying all those big photos around [in a scene where she’s preparing for an exhibition] and I say ‘Why are they like that, in this sequence, why? It’s inexplicable’. . . It goes right back to these last words.

Keyframe: You need to deconstruct something first to make it fully happen. Every gaze you make reconstructs what you’re seeing—I was mesmerized by these poignant thoughts carried by Carolee’s work and now Marielle’s film.

Schneemann: But this gaze also reconstructs, with the blind recognition that has all the aspects of intuition—which means your skill, your history—that you trust this juxtaposition, you trust this cut. You trust this focus. It has a fluidity that’s beyond conceptual.

Nitoslawska: Nothing is closed, everything is connected, flows in and out. Nothing is made linear, predictable, finite. Everything has this open possibility of entrance.

Keyframe: Carolee, everybody familiar with your work know, how important your house, your surrounding is for your art. I think of it as your natural habitat. Marielle, how did you feel it when you first got to New Paltz?

Nitoslawska: That really was the determining factor for making the film. In cinema you have to have a place to put the camera—it’s as simple as that. I still remember when me and my two students arrived there to scan. My very first visit to New Paltz. It was about four, maybe five in the afternoon, beautiful sun setting. I walked out of the car and said: ‘I’m making this film.’ Then, as I built the sequence, I started to think of the house as another body. A kind of an encompassing body with all the complexity of bodies. A living one that surrounds you.

Schneemann: Someone called my house ‘a line through.’ Its incarnations as film, as past, as present. . . it made a line though time.

Nitoslawksa: It is this timeless, stable presence.

Keyframe: It reminded me of a beating heart, with all its rooms, hiding spaces and magical chambers. . . .

Nitoslawska: What I’m interested in as a filmmaker is how we respond to spaces and how we communicate that. So a lot of the sequences are reconstructions of my experiences there. One of the early realizations was, Carolee would go somewhere, I’d be in the house and I felt like I don’t know what time I’m in. I’m here, in the present, feeling as if I was there when Fuses was shot. A lot of people say my film is not a documentary; I think it is an über-documentary! It goes to this level when you’re not just recording, but trying to express with images and sounds, what you know, have experienced and lived through.

Schneemann: No one has ever addressed my work without compromising my dynamic. Marielle’s perspective is utterly generous, caring and inclusive. I’ve always had documentations or other people’s writing about me, when I felt distorted. ‘This is not really me’—I thought—’they needed to make something out of what they saw.’ And it’s really painful. This experience, on the other hand, was a complete joy. I never knew what she was doing exactly, so it was quite odd this way as well.

Keyframe: I feel like the commonly assumed existence of an existing division between the public and the private has been treated subversively in Carolee’s work. I remember this moment in the film when Marielle approaches Carolee when working, and Carolee says ‘Oh! I thought I had a moment of privacy!’ Then she laughs.

[They both laugh. ]

Nitoslawska: For me such division is a real issue. There are some materials that are fantastic but I felt go beyond that line and I didn’t use them.

Schneemann: That issue to me relates to the very first sequence she presents—of the dead chipmunk. I said: ‘Look, that’s outrageous, people are gonna be very upset that the cat did this!’. . . but it’s a riot. And it’s the essence of everything in my life. You see the body of this creature, I think it’s in a film tin—gotta get rid of it by the way—and then Marielle cuts to my cat sitting in the window with this completely innocent look.

Keyframe: The crossing of all types of borders is something Carolee always did herself. What’s the difference when such act it involves other people, like Marielle in Breaking the Frame?

Schneemann: The issue of private space is very important to me if I have the implicit presentation of it, if I trust my need to bring it forward. And I trusted her need to bring it forward. With other people, I’d been appalled, as she has also shown it in Breaking the Frame—like the really traumatic intensities with Stan Brakhage, where thing were just wrong. . . and many other instances [Schnemann refers to the situation with Brakhage’s Cat’s Cradle. Brakhage shot her while she was painting a portrait of Jane Brakhage. Schneemann wished to be portrayed as an artist, but was shown chopping onions instead. Nitoslawska told Huffington Post: ‘I couldn’t believe it when we found five frames of Carolee doing just that, hidden in the Brakhage film. They were there but couldn’t be perceived, since five frames is a fifth of a second in projection. So we multiplied the five frames, slowed them right down, and Carolee finally got her due [via Brakhage] fifty years later.’ Marielle has a great sense of humor and I was always recognizing this other layer as well, it was wonderful to bring it forward.

Nitoslawska: When you make a decision to bring it forward there has got to be a good reason for it. It’s gotta be something that is greater than itself. The story with Brakhage is not in the sphere of gossip, but history. And how history it’s made. It has to have a kind of lingering of meanings.

Schneemann: You said before that something might be outrageous, but have its grace of implicit meaning. And if we have that, then it is acceptable to me and inconsequential. It has to be able to move in my sense of what we can perceive.

Keyframe: Carolee is a collector. The house is full of thermometers, postcards. The diaries are also a part of the ‘collectress universe.’ Carolee, what drives you to keep saving those memories in physical form?

Schneemann: I don’t like the idea of it, but the reality has to do with the idea of retrieval. Trying to maintain and have a trace of everything that communicates, and might have some precious essence, without being so precious itself. Just a card. . . .I get things from my students that are very precious to me, because it’s some essence of them in it. I threw out a lot, I don’t like to accumulate things. But then—look, how much you have to work with! Marielle, what about your collecting? Your studio is impenetrable! You can hardly walk through all those papers!

Nitoslawska: I don’t keep as much as you do…

Schneemann: [Laughs. ]

Nitoslawska: . . . but I do keep. The exhibition in WRO Art Center is based on the Carolee’s Life Books, which is also collecting. I’m really interested in this aspect of your work, because through it we can understand that all your work is absolutely, organically connected to living. It’s not that through collecting they become dead objects; in fact they can be forever recollected. These objects in some way have a life of their own.

Schneemann: That would be good.

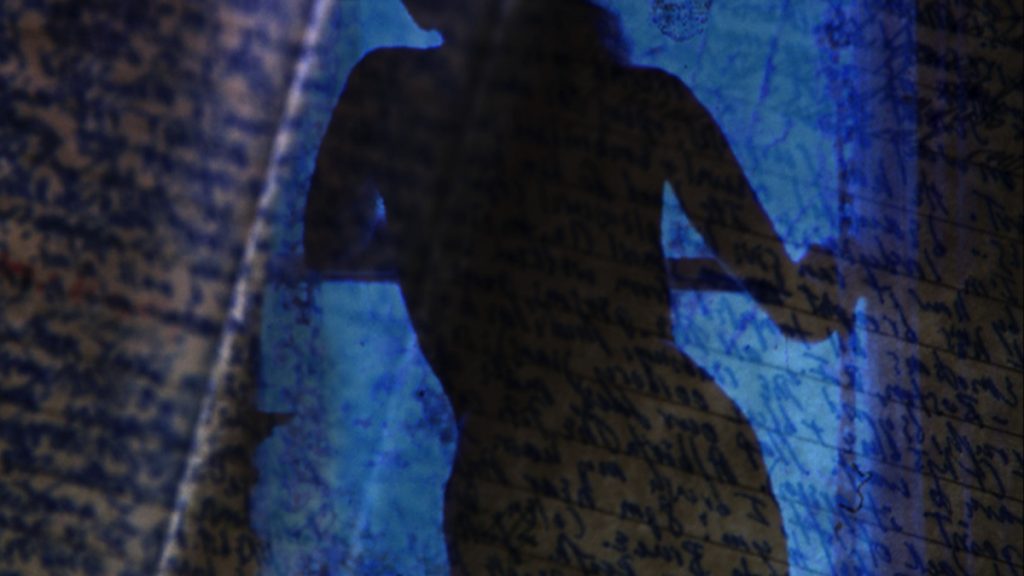

Keyframe: There’s this amazing shot in the film: one of Carolee’s diaries is open, Marielle shoots it from a low angle, the light’s coming through the page and we can see those other pages. The words blur in, disappear, merge and the shot becomes art itself.

Nitoslawska: I’ve always thought of those Life Books as of non-objects. They’ve never been shown, because they are… very hard to show. We photographed them in very, very hight definition..

Schneemann: They’re never literalized when you’re photographing. That’s what’s so beautiful. Marielle brings a poetic intensity to how she’s looking at those things. So they’re never made prosaic. They may be kind of ordinary in some way, but with her eye on it they’re really a transcendent realm, and particularly we see that with Terminal Velocity. That was so incredible, unbelievable… Who would have thought to take them down, wrap them up in a big glove of hands over them and that would be such an essence. . . [Schneemann refers to how this particular work was shown in he film. As Nitoslawska comments: Terminal Velocity ‘ it’s the 9/11 scene, the work that is made from the famous newspaper images of people jumping off the World Trade Center… I had filmed the work several times before realizing that its power will emerge only if I film it with living hands and bodies interacting with it, as in a life-death dialectic.’ ]

Nitoslawska: That’s because it’s like a sacred burial.

Schneemann: You tried to shoot them upright, but it wasn’t working…

Nitoslawska: It didn’t give me the experience of perceiving the work. That’s really what you can do, when you’re making a film whose subject is art. I have to look at the work and constantly think: ‘what’s happening there?’ The reason these falling bodies are so incredible is because we actually project ourselves on them. We see them as living bodies. And the only way to show that is to put them with living bodies.

Keyframe: Are there things impossible to transmit through the filter of artist’s sensitivity? Are there things that will never come out?

Schneemann: Yeah, the way their sweat smells [Laughs. ]

Nitoslawska: I think we’re always just trying, there’s nothing finite. It’s an ongoing process.

Keyframe: After this time spent with you I feel like I can ask you about your former partner, the late James Tenney. He was not only a part of your life, but also is one of the pillars of Breaking the Frame. His music is carrying and embracing the film and he’s a very steady presence in this picture.

Schneemann: He’s my big love, he’s the essence of everything I’ve done and his essence is in all the work and time.

Nitoslawska: The very first images I filmed were of him at the MOMA, playing piano. I didn’t have money to make this film when I shot them, but I always knew that I wanted to have his music in the film. But it was only in editing when I understood why. It often happens in our work: something is intuitive and then we get to a point where we start to understand what that intuition is about. I understood that he’s like a magician. Sort of a secret force, mysterious energy. But also: what is love? Love is exactly that: the mysterious energy. The grace that goes beyond the personal sphere. It’s not in that sphere anymore. It’s a profound connection that suddenly puts a cast on everything. There’s this beautiful sequence where he hits a note and the drop falls. He’s a presence that makes things happen. The part with him I prepared for the film was something I was sure about, but I didn’t know if Carolee would accept it. And then Lauren, his wife, came. It was very important to me for her to see the film as well.

Schneemann: And for me, because she was my best friend and when his younger wife died I introduced them, and I was so happy that they became a couple. It is hard for some people to understand, but when Jim died, Lauren and I were like two widows together, holding hands. Her valuing and cherishing the film is another magic.

Keyframe: Carolee, you once attempted using your art as a cure. When James was diagnosed with cancer in 1989 you created Jim’s Lungs.

Schneemann: The mythical prosaic. To pick up a crayon and think: ‘I wonder if these strokes can interfere with cancer cells.’ It’s crazy.

Keyframe: But your paintings, they did work.

Schneemann: Jim said so. It’s an inexplicable experiment.

Keyframe: Maybe this is what is commonly understood as the power of art?

Nitoslawska: I’ve had people come up to me after seeing Breaking the Frame and say: ‘I now know I have to go home and write something, make something.’ It gives back a kind of a power. If film, art can do that… To me that’s the best.

Schneemann: This is my premise as a pantheist.

Keyframe: So what does one do and how did you become one?

Schneemann: Someone the other day asked me whether I was a Buddhist. ‘No, I’m a pantheist,’ I replied. That’s what I used to say when I was a kid. My parents had divided religions and we didn’t like any of them. They’d ask me: ‘What are you gonna be?’ and I don’t remember where I got the idea from, I was very young, but I said: ‘pantheist!’ It was my habit to always disappear in nature when I was a kid, I thought that’s what a pantheist does. And I still do. Besides, I though it had to do with a panther. And that the word ‘painting’ was in there as well.