[Editor’s note: This is the sixth entry in our ‘Video Evidence’ series on the Oscar race. For the complete list of ‘Who Really Deserves to Win’ essays, visit our Oscars 2015 landing page.]

We all have our reasons for loving the movies: inspiring stories, intense emotions, complex characters, visionary journeys. I personally hold a special place for films that don’t just offer escape, but spark a new engagement with the world I live in. But even more exceptional are films that make me aware of how filmmaking connects us to the world. This was true of my five favorite films of 2014: each one brilliantly explores the role that filmmaking plays in exploring our realities. I wish this quality were more present among the eight films nominated for this year’s Best Picture Oscar.

The Imitation Game and The Theory of Everything are run-of-the-mill awards bait: single-serving stories of inspirational men presented as handsomely as possible, where high production values are a poor substitute for cinematic ingenuity. There’s much better filmmaking in American Sniper and Whiplash, two films that focus on a male hero’s obsessive quest for glory and the toll it takes on his psyche. Both films rely heavily on subjective techniques that suck the viewer into their hero’s mental state. I recognize the power of this kind of seductive, manipulative filmmaking, but I’d rather have a film that gives room for me to step outside that narrow view and see more openly. Even a film that’s as controlling as The Grand Budapest Hotel has a lightness that invites you to wonder about the construction of this elaborate storytelling contraption even as it carries you away.

The question of how to find freedom in the movies is not something to take for granted. Selma has received harsh criticism for distorting certain historical facts, which is a cruel irony for a film whose underlying topic is how history gets distorted by political oppression. One of the things I like most about it are the titles that replicate FBI surveillance reports on the activities of Martin Luther King and other civil rights activists. It makes one aware of the power struggles that exist in how history gets written. This is crucial to understanding why this film is an even greater achievement than last year’s Best Picture winner, Twelve Years a Slave – instead of appealing to sentimental notions of black suffering in the past, Selma is about the possibility of attaining black power in the present. This isn’t just another Hollywood prestige picture, but a thoughtful and powerful work of minority storytelling for a mainstream audience: not just to entertain, but to mobilize to action.

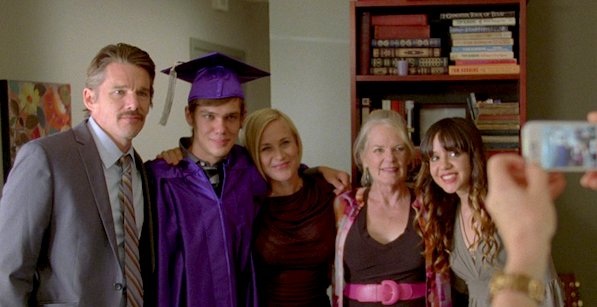

I’ve expressed my doubts about Boyhood in other videos, a film that manages to be both radically experimental and ideologically square. It’s a masterpiece of middle class lives and values that might be too easy-going for its own good. It’s not until I start to dig into it that it starts to fascinate me. Like when I cut the film up to see how its twelve-year time span breaks down. The film is 160 minutes, about an average of thirteen minutes for each year. But some years are well below average: year eight is only four minutes long. Is it because the scenes he filmed that year weren’t as good, or didn’t fit into the arc of the story? And why does Ethan Hawke have twenty-five percent more time in the movie than Patricia Arquette, even though her character is the one who lives with the main character? Is it because boys are meant to bond with their dads instead of their moms? Is it a lack of the filmmaker’s consideration to develop the mother further? Or is it because Ethan Hawke is a skillful improviser who could generate more interesting material for his scenes? All these questions point to what I value most about Boyhood: it’s a film that calls attention to its own creative process, and invites viewers to take an active stake in the act of creation by asking questions about it. The content of the movie may amount to a bland exercise in normcore nostalgia, but the form is a radical achievement by mainstream standards.

Birdman is another film that goes down very easily, and provokes as many reasons to be skeptical. Yes, it’s bombastic and cartoonish, full of sweeping gestures and simplistic notions on art and entertainment. Yes, its characters are a bunch of show business stereotypes, and its Spielberg Face ending feels false. But as with Boyhood, it achieves its complexity purely in the realm of cinema. If you get past all those reasons to dismiss it, it works brilliantly on the most abstract levels, as movement through space, time, light, color and sound. As with Boyhood, it’s focused on an ever unfolding now, except that this moment never ends with an eye that never closes. More than any of the other films, its eyes are intensely engaged with its space, always searching for how to shape the moment to express its feelings. In that sense, the camerawork is more profound than any lines in the script, because it’s the kind of camerawork that provokes us to think about how we move through the world, moment by moment. The way this movie inhabits its space asks a basic question: how do we want to live in our spaces to find as much beauty as we can in every moment? This may be one of the most essential questions that the art of cinema was made to ask.

Kevin B. Lee is a filmmaker, critic, video essayist and founding editor of Keyframe. His video essay Transformers: The Premake will screen at the International Film Festival Rotterdam and the Berlinale International Film Festival Critics’ Week. He tweets at @alsolikelife.