Peter Greenaway is not an easy filmmaker to get into and, one suspects, that’s just the way he likes it. Given that his films are filled to the corners of every frame with detailed references to paintings, literature, theatre, natural history, and a plethora of inside jokes, his work has often attracted the charge of elitism. And that’s all before you get to his disapproval, sometimes even outright contempt, for cinema focused around narrative, text, and script. “All screenwriters should be shot,” he proclaimed in his 2016 BAFTA interview ‘Peter Greenaway: A Life in Pictures. He smiled as he said it, but he would clearly rather shoot a phone book than someone else’s screenplay.

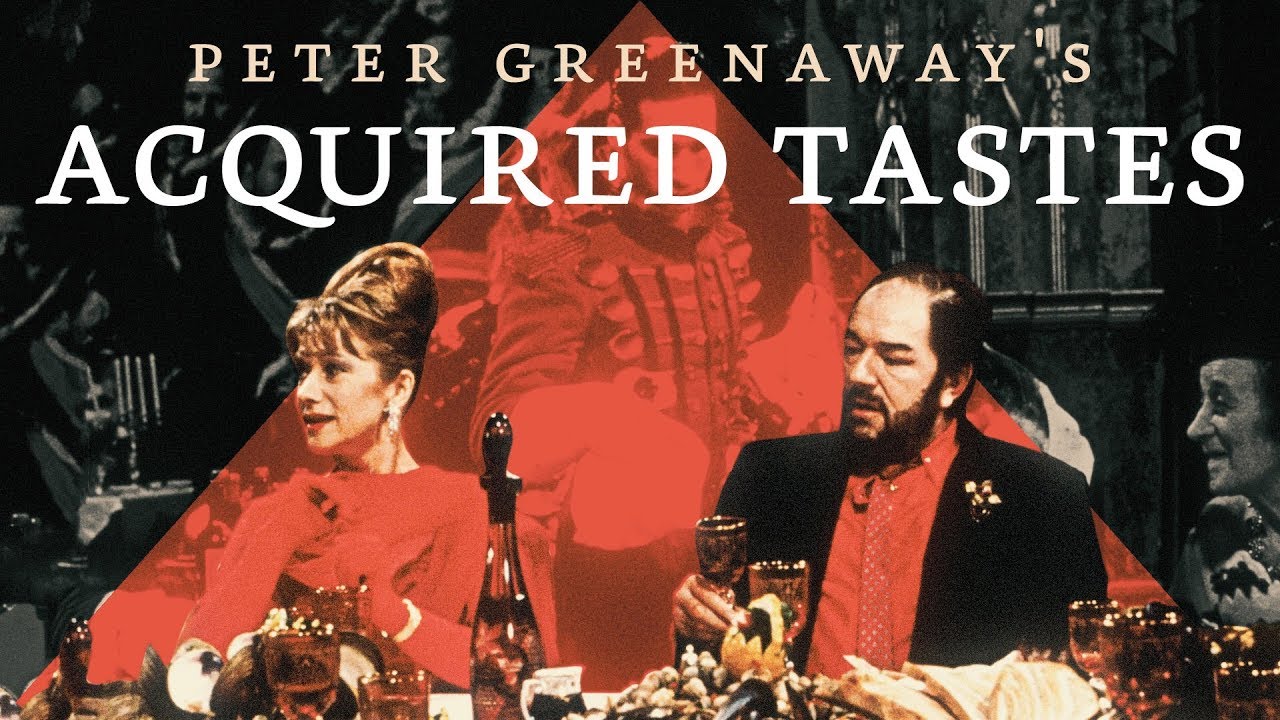

His 1989 film The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover is savage and sadistic, beautiful and brilliant. Whether or not it functions as a metaphor for Thatcher’s Britain, as some claim, it certainly works as an expression of Greenaway’s style, and love, of art — fine art, to be precise. The framing tableaux, shifting swathes of color, exhibition-style set decoration, and the wall-sized Frans Hals portrait looming over all proceedings all harks back to his lifelong desire to see “paintings with soundtracks”. And while Michael Nyman’s relentless score accompanies vast sections of the film, so too do the fearless performances of actors like Helen Mirren and Michael Gambon (anyone who knows him as gentle Albus Dumbledore from Harry Potter is in for a severe shock at a villain to rival Voldemort himself), and the gruesome, Jacobean-like revenge drama they enact… all while outfitted in costumes by Jean Paul Gaultier.

It’s arguably this fusion of narrative alongside Greenaway’s image-based cinema that has made it – perhaps alongside The Draughtsman’s Contract – his most accessible and acclaimed feature. A filmmaker as uncompromising as Greenaway would doubtless claim that this proves his point, that audiences flounder without the safety net of story, and that’s why this film (and not, say, his multi-part, multimedia experience The Tulse Luper Suitcases) is his most popular work. But there’s an opposing argument: that image-based cinema needn’t dismiss narrative entirely. And surely a lover of symmetry like Greenaway might find something valid in such a counterbalancing claim.